Constantine I, also known as Constantine the Great, was a Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337 and the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity. He played a pivotal role in elevating the status of Christianity in Rome, decriminalizing Christian practice and ceasing Christian persecution in a period referred to as the Constantinian shift. This initiated the cessation of the established ancient Roman religion. Constantine is also the originator of the religiopolitical ideology known as Constantinianism, which epitomizes the unity of church and state, as opposed to separation of church and state. He founded the city of Constantinople and made it the capital of the Empire, which remained so for over a millennium.

Year 331 (CCCXXXI) was a common year starting on Friday of the Julian calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Bassus and Ablabius. The denomination 331 for this year has been used since the early medieval period, when the Anno Domini calendar era became the prevalent method in Europe for naming years.

Constantine IV, called the Younger and often incorrectly the Bearded out of confusion with his father, was Byzantine emperor from 668 to 685. His reign saw the first serious check to nearly 50 years of uninterrupted Islamic expansion, most notably when he successfully defended Constantinople from the Arabs, and the temporary stabilization of the Byzantine Empire after decades of war, defeats, and civil strife. His calling of the Sixth Ecumenical Council saw the end of the monothelitism controversy in the Byzantine Empire; for this, he is venerated as a saint in the Eastern Orthodox Church, with his feast day on September 3.

Constantine V was Byzantine emperor from 741 to 775. His reign saw a consolidation of Byzantine security from external threats. As an able military leader, Constantine took advantage of civil war in the Muslim world to make limited offensives on the Arab frontier. With this eastern frontier secure, he undertook repeated campaigns against the Bulgars in the Balkans. His military activity, and policy of settling Christian populations from the Arab frontier in Thrace, made Byzantium's hold on its Balkan territories more secure. He was also responsible for important military and administrative innovations and reforms.

Byzantine art comprises the body of artistic products of the Eastern Roman Empire, as well as the nations and states that inherited culturally from the empire. Though the empire itself emerged from the decline of western Rome and lasted until the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, the start date of the Byzantine period is rather clearer in art history than in political history, if still imprecise. Many Eastern Orthodox states in Eastern Europe, as well as to some degree the Islamic states of the eastern Mediterranean, preserved many aspects of the empire's culture and art for centuries afterward.

During the reign of the Roman emperor Constantine the Great (306–337 AD), Christianity began to transition to the dominant religion of the Roman Empire. Historians remain uncertain about Constantine's reasons for favoring Christianity, and theologians and historians have often argued about which form of early Christianity he subscribed to. There is no consensus among scholars as to whether he adopted his mother Helena's Christianity in his youth, or, as claimed by Eusebius of Caesarea, encouraged her to convert to the faith he had adopted.

The Great Palace of Constantinople, also known as the Sacred Palace, was the large imperial Byzantine palace complex located in the south-eastern end of the peninsula now known as Old Istanbul, in modern Turkey. It served as the main imperial residence of the Eastern Roman emperors until 1081 and was the centre of imperial administration for over 690 years. Only a few remnants and fragments of its foundations have survived into the present day.

The Barberini ivory is a Byzantine ivory leaf from an imperial diptych dating from Late Antiquity, now in the Louvre in Paris. It represents the emperor as triumphant victor. It is generally dated from the first half of the 6th century and is attributed to an imperial workshop in Constantinople, while the emperor is usually identified as Justinian, or possibly Anastasius I or Zeno. It is a notable historical document because it is linked to queen Brunhilda of Austrasia. On the back there is a list of names of Frankish kings, all relatives of Brunhilda, indicating her important position. Brunhilda ordered the list to be inscribed and offered it to the church as a votive image.

The Byzantine Iconoclasm were two periods in the history of the Byzantine Empire when the use of religious images or icons was opposed by religious and imperial authorities within the Ecumenical Patriarchate and the temporal imperial hierarchy. The First Iconoclasm, as it is sometimes called, occurred between about 726 and 787, while the Second Iconoclasm occurred between 814 and 842. According to the traditional view, Byzantine Iconoclasm was started by a ban on religious images promulgated by the Byzantine Emperor Leo III the Isaurian, and continued under his successors. It was accompanied by widespread destruction of religious images and persecution of supporters of the veneration of images. The Papacy remained firmly in support of the use of religious images throughout the period, and the whole episode widened the growing divergence between the Byzantine and Carolingian traditions in what was still a unified European Church, as well as facilitating the reduction or removal of Byzantine political control over parts of the Italian Peninsula.

Porphyrius the Charioteer, also named Porphyrius Calliopas was a celebrity Byzantine-Roman charioteer in the late 5th and early 6th century AD, during what the classicist Alan Cameron has described as the "golden age" of Byzantium's hippodrome, and of the Byzantine charioteer.

The Augustaion or, in Latin, Augustaeum, was an important ceremonial square in ancient and medieval Constantinople, roughly corresponding to the modern Aya Sofya Meydanı. Originating as a public market, in the 6th century it was transformed into a closed courtyard surrounded by porticoes, and provided the linking space between some of the most important edifices in the Byzantine capital. The square survived until the late Byzantine period, albeit in ruins, and traces were still visible in the early 16th century.

The Philadelphion was a public square located in Constantinople.

The Palace of Antiochos was an early 5th-century palace in the Byzantine capital, Constantinople. It has been identified with a palatial structure excavated in the 1940s and 1950s close to the Hippodrome of Constantinople, some of whose remains are still visible today. In the 7th century, a part of the palace was converted into the church–more properly a martyrion, a martyr's shrine–of St Euphemia in the Hippodrome, which survived until the Palaiologan period.

The Palace of Daphne was one of the major wings of the Great Palace of Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire. According to George Codinus, it was named after a statue of the nymph Daphne, brought from Rome. The exact layout and appearance of the palace is unclear, since it lies under the Sultan Ahmed Mosque, and the only surviving evidence comes from literary sources. Jonathan Bardill, however, has suggested that the peristyle with mosaics adjoining an apsed hall, excavated by the Walker Trust excavations in 1935-7 and 1952-4, could be the Augusteus of the Daphne Palace.

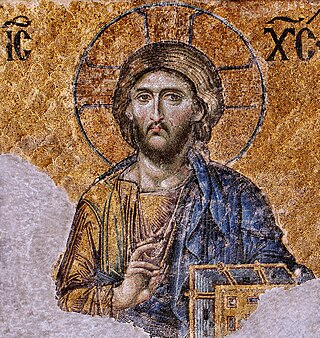

The Chalke Gate, was the main ceremonial entrance (vestibule) to the Great Palace of Constantinople in the Byzantine period. The name, which means "the Bronze Gate", was given to it either because of the bronze portals or from the gilded bronze tiles used in its roof. The interior was lavishly decorated with marble and mosaics, and the exterior façade featured a number of statues. Most prominent was an icon of Christ which became a major iconodule symbol during the Byzantine Iconoclasm, and a chapel dedicated to the Christ Chalkites was erected in the 10th century next to the gate. The gate itself seems to have been demolished in the 13th century, but the chapel survived until the early 19th century.

Parastaseis syntomoi chronikai is an eighth- to ninth-century Byzantine text that concentrates on brief commentary connected to the topography of Constantinople and its monuments, notably its Classical Greek sculpture, for which it has been mined by art historians.

The Patria of Constantinople, also regularly referred to by the Latin name Scriptores originum Constantinopolitarum, are a Byzantine collection of historical works on the history and monuments of the Byzantine imperial capital of Constantinople.

Tiberius was Byzantine co-emperor from 659 to 681. He was the son of Constans II and Fausta, who was elevated in 659, before his father departed for Italy. After the death of Constans, Tiberius' brother Constantine IV, ascended the throne as senior emperor. Constantine attempted to have both Tiberius and Heraclius removed as co-emperors, which sparked a popular revolt, in 681. Constantine ended the revolt by promising to accede to the demands of the rebels, sending them home, but bringing their leaders into Constantinople. Once there, Constantine had them executed, then imprisoned Tiberius and Heraclius and had them mutilated, after which point they disappear from history.

The Religious policies of Constantine the Great have been called "ambiguous and elusive." Born in 273 during the Crisis of the Third Century, Constantine the Great was thirty at the time of the Great Persecution. He saw his father become Augustus of the West and then shortly die. Constantine spent his life in the military warring with much of his extended family, and converted to Christianity sometime around 40 years of age. His religious policies, formed from these experiences, comprised increasing toleration of Christianity, limited regulations against Roman polytheism with toleration, participation in resolving religious disputes such as schism with the Donatists, and the calling of councils including the Council of Nicaea concerning Arianism. John Kaye characterizes the conversion of Constantine, and the Council of Nicea that Constantine called, as two of the most important things to ever happen to the Christian church.

Thekla, Latinized as Thecla, was a princess of the Amorian dynasty of the Byzantine Empire. The eldest child of Byzantine emperor Theophilos and empress Theodora, she was proclaimed augusta in the late 830s. After Theophilos's death in 842 and her mother becoming regent for Thekla's younger brother, Michael III, Thekla was associated with the regime as co-empress alongside Theodora and Michael.