Aten also Aton, Atonu, or Itn was the focus of Atenism, the religious system formally established in ancient Egypt by the late Eighteenth Dynasty pharaoh Akhenaten. Exact dating for the 18th dynasty is contested, though a general date range places the dynasty in the years 1550 to 1292 B.C.E. The worship of Aten and the coinciding rule of Akhenaten are major identifying characteristics of a period within the 18th dynasty referred to as the Amarna Period.

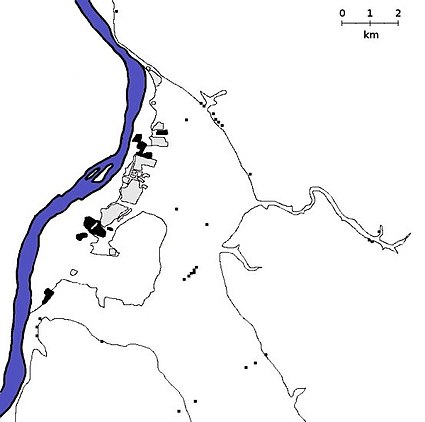

Amarna is an extensive Egyptian archaeological site containing the remains of what was the capital city of the late Eighteenth Dynasty. The city was established in 1346 BC, built at the direction of the Pharaoh Akhenaten, and abandoned shortly after his death in 1332 BC. The name that the ancient Egyptians used for the city is transliterated as Akhetaten or Akhetaton, meaning "the horizon of the Aten".

Akhenaten, also spelled Akhenaton or Echnaton, was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh reigning c. 1353–1336 or 1351–1334 BC, the tenth ruler of the Eighteenth Dynasty. Before the fifth year of his reign, he was known as Amenhotep IV.

Nefertiti was a queen of the 18th Dynasty of Ancient Egypt, the great royal wife of Pharaoh Akhenaten. Nefertiti and her husband were known for their radical overhaul of state religious policy, in which they promoted the earliest known form of monotheism, Atenism, centered on the sun disc and its direct connection to the royal household. With her husband, she reigned at what was arguably the wealthiest period of ancient Egyptian history. Some scholars believe that Nefertiti ruled briefly as Neferneferuaten after her husband's death and before the ascension of Tutankhamun, although this identification is a matter of ongoing debate. If Nefertiti did rule as Pharaoh, her reign was marked by the fall of Amarna and relocation of the capital back to the traditional city of Thebes.

Meritaten, also spelled Merytaten, Meritaton or Meryetaten, was an ancient Egyptian royal woman of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt. Her name means "She who is beloved of Aten"; Aten being the sun-deity whom her father, Pharaoh Akhenaten, worshipped. She held several titles, performing official roles for her father and becoming the Great Royal Wife to Pharaoh Smenkhkare, who may have been a brother or son of Akhenaten. Meritaten also may have served as pharaoh in her own right under the name Ankhkheperure Neferneferuaten.

Atenism, also known as the Aten religion, the Amarna religion, and the Amarna heresy, was a religion in ancient Egypt. It was founded by Akhenaten, a pharaoh who ruled the New Kingdom under the Eighteenth Dynasty. The religion is described as monotheistic or monolatristic, although some Egyptologists argue that it was actually henotheistic. Atenism was centred on the cult of Aten, a god depicted as the disc of the Sun. Aten was originally an aspect of Ra, Egypt's traditional solar deity, though he was later asserted by Akhenaten as being the superior of all deities. In the 14th century BC, Atenism was Egypt's state religion for around 20 years, and Akhenaten met the worship of other gods with persecution; he closed many traditional temples, instead commissioning the construction of Atenist temples, and also suppressed religious traditionalists. However, subsequent pharaohs toppled the movement in the aftermath of Akhenaten's death, thereby restoring Egyptian civilization's traditional polytheistic religion. Large-scale efforts were then undertaken to remove from Egypt and Egyptian records any presence or mention of Akhenaten, Atenist temples, and Atenist assertions of a uniquely supreme god.

The Amarna Period was an era of Egyptian history during the later half of the Eighteenth Dynasty when the royal residence of the pharaoh and his queen was shifted to Akhetaten in what is now Amarna. It was marked by the reign of Amenhotep IV, who changed his name to Akhenaten in order to reflect the dramatic change of Egypt's polytheistic religion into one where the sun disc Aten was worshipped over all other gods. The Egyptian pantheon was restored under Akhenaten's successor, Tutankhamun.

The Boundary Stelae of Akhenaten are a group of royal monuments in Upper Egypt. They are carved into the cliffs surrounding the area of Akhetaten, or the Horizon of Aten, which demarcates the limits of the site. The Pharaoh Akhenaten commissioned the construction of Akhetaten in year five of his reign during the New Kingdom. It served as a sacred space for the god Aten in an uninhabited location roughly halfway between Memphis and Thebes at today's Tell El-Amarna. The boundary stelae include the foundation decree of Akhetaten along with later additions to the text, which delineate the boundaries and describe the purpose of the site and its founding by the Pharaoh. Total of sixteen stelae have been discovered around the area. According to Barry Kemp, the Pharaoh Akhenaten did not “conceive of Akhetaten as a city, but as a tract of sacred land”.

Panehesy was an Egyptian noble who bore the titles of 'Chief servitor of the Aten in the temple of Aten in Akhetaten'.

The Workmen's Village, located in the desert 1.2 kilometres (0.75 mi) east of the ancient city of Akhetaten, was built during the reign of the Eighteenth Dynasty pharaoh Akhenaten. It housed the workers who constructed and decorated the tombs of the city's elite, making it comparable to the better studied Theban workers village of Deir el-Medina. Though an isolated part of Amarna, the Workmen's Village provides many well preserved artifacts and buildings allowing archaeologists to gather much information about how society functioned.

Maru-Aten, short for Pa-maru-en-pa-aten, is a palace or sun-temple located 3 km to the south of the central city area of the city of Akhetaten. It is thought to have been originally constructed for Akhenaten's queen Kiya, but on her death her name and images were altered to those of Meritaten, his daughter.

The Great Temple of the Aten was a temple located in the city of el-Amarna, Egypt. It served as the main place of worship of the deity Aten during the reign of the 18th Dynasty pharaoh Akhenaten. Akhenaten ushered in a unique period of ancient Egyptian history by establishing the new religious cult dedicated to the sun-disk Aten, originally an aspect of Ra, the sun god in traditional ancient Egyptian religion. The king shut down traditional worship of other deities like Amun-Ra, and brought in a new era, though short-lived, of seeming monotheism where the Aten was worshipped as a sun god and Akhenaten and his wife, Nefertiti, represented the divinely royal couple that connected the people with the god. Although he began construction at Karnak during his rule, the association the city had with other gods drove Akhenaten to establish a new city and capital at Amarna for the Aten. Akhenaten built the city along the east bank of the Nile River, setting up workshops, palaces, suburbs and temples. The Great Temple of the Aten was located just north of the Central City and, as the largest temple dedicated to the Aten, was where Akhenaten fully established the proper cult and worship of the sun-disk.

The Small Aten Temple is a temple to the Aten located in the ancient Egyptian city of Amarna. It is one of the two major temples in the city, the other being the Great Temple of the Aten. It is situated next to the King's House and near the Royal Palace, in the central part of the city. Original known as the Hwt-Jtn or Mansion of the Aten, it was probably constructed before the larger Great Temple. Its only contemporary depiction is found in the tomb of Tutu. Like the other structures in the city, it was constructed quickly, and hence was easy to dismantle and reuse the material for later construction.

Mahu was Chief of Police at Akhetaten.

The North City was an administrative area in the ancient Egyptian city of Amarna in Upper Egypt, the short-lived capital of Pharaoh Akhenaten of the 18th Dynasty. It contains the ruins of royal palaces, especially the Northern Palace and other administrative buildings and occupies an area between the river and the cliffs that terminate the plains to the north of the city itself.

Nakhtpaaten or Nakht was an ancient Egyptian vizier during the reign of Pharaoh Akhenaten of the 18th Dynasty.

Amarna Tomb 3 is a rock-cut cliff tomb located in Amarna, Upper Egypt. The tomb belonged to the Ancient Egyptian noble Ahmes (Ahmose), who served during the reign of Akhenaten. The tomb is situated at the base of a steep cliff and mountain track at the north-eastern end of the Amarna plains. It is located in the northern side of the wadi that splits the cluster of graves known collectively as the Northern tombs. Amarna Tomb 3 is one of six elite tombs belonging to the officials of Akhenaten. It was one of the first Northern tombs, built in Year 9 of the reign of Akhenaten.

Amarna Tomb 5 is an ancient sepulchre in Amarna, Upper Egypt. It was built for the courtier Pentu, and is one of the six Northern tombs at Amarna. The burial is located to the south of the tomb of Meryra. It is very similar to the tomb of Ahmes. The sepulchre is T-shaped and its inner chamber would have served as the burial chamber.

The Amarna Era includes the reigns of Akhenaten, Smenkhkare, Tutankhamun and Ay. The period is named after the capital city established by Akhenaten, son of Amenhotep III. Akhenaten started his reign as Amenhotep IV, but changed his name when he discarded all other religions and declared the Aten or sun disc as the only god. He closed all the temples of the other Gods and removed their names from the monuments. Smenkhkare, then Tutankhamun, succeeded Akhenaten. Discarding Akhenten's religious beliefs, Tutankhamun returned to the traditional gods. He died young and was succeeded by Ay. Many kings did their best to remove all traces of the period from the records. The Amarna art is very distinctive: the royal family was portrayed with extended heads, long necks and narrow chests. They had skinny limbs, but heavy hips and thighs, with a marked stomach.

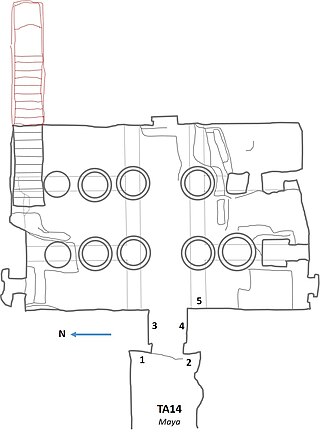

May was an ancient Egyptian official during the reign of Pharaoh Akhenaten. He was Royal chancellor and fan-bearer at Akhet-Aten, the pharaoh's new capital. He was buried in Tomb EA14 in the southern group of the Amarna rock tombs. Norman de Garis Davies originally published details of the Tomb in 1908 in the Rock Tombs of El Amarna, Part V – Smaller Tombs and Boundary Stelae. The tomb dates to the late 18th Dynasty.