KV55 is a tomb in the Valley of the Kings in Egypt. It was discovered by Edward R. Ayrton in 1907 while he was working in the Valley for Theodore M. Davis. It has long been speculated, as well as much disputed, that the body found in this tomb was that of the famous king, Akhenaten, who moved the capital to Akhetaten. The results of genetic and other scientific tests published in February 2010 have confirmed that the person buried there was both the son of Amenhotep III and the father of Tutankhamun. Furthermore, the study established that the age of this person at the time of his death was consistent with that of Akhenaten, thereby making it almost certain that it is Akhenaten's body. However, a growing body of work soon began to appear to dispute the assessment of the age of the mummy and the identification of KV55 as Akhenaten.

The tomb of Tutankhamun, also known by its tomb number, KV62, is the burial place of Tutankhamun, a pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of ancient Egypt, in the Valley of the Kings. The tomb consists of four chambers and an entrance staircase and corridor. It is smaller and less extensively decorated than other Egyptian royal tombs of its time, and it probably originated as a tomb for a non-royal individual that was adapted for Tutankhamun's use after his premature death. Like other pharaohs, Tutankhamun was buried with a wide variety of funerary objects and personal possessions, such as coffins, furniture, clothing and jewelry, though in the unusually limited space these goods had to be densely packed. Robbers entered the tomb twice in the years immediately following the burial, but Tutankhamun's mummy and most of the burial goods remained intact. The tomb's low position, dug into the floor of the valley, allowed its entrance to be hidden by debris deposited by flooding and tomb construction. Thus, unlike other tombs in the valley, it was not stripped of its valuables during the Third Intermediate Period.

Tomb KV17, located in Egypt's Valley of the Kings, is the tomb of Pharaoh Seti I of the Nineteenth Dynasty. It is also known by the names "Belzoni's tomb", "the Tomb of Apis", and "the Tomb of Psammis, son of Nechois". It is one of the most decorated tombs in the valley, and is one of the largest and deepest tombs in the Valley of the Kings. It was uncovered by Italian archaeologist and explorer Giovanni Battista Belzoni on 16 October 1817.

Tomb WV23, also known as KV23, is located in the Western Valley of the Kings near modern-day Luxor, and was the tomb of Pharaoh Ay of the Eighteenth Dynasty. The tomb was discovered by Giovanni Battista Belzoni in the winter of 1816. Its architecture is similar to that of the tomb of Akhenaten, with a straight descending corridor leading to a "well chamber" that has no shaft. This leads to the burial chamber, which now contains the reconstructed sarcophagus, which had been smashed in antiquity. The tomb had also been anciently desecrated, with many instances of Ay's image or name erased from the wall paintings. Its decoration is similar in content and colour to that of the tomb of Tutankhamun (KV62), with a few differences. On the eastern wall there is a depiction of a fishing and fowling scene, which is not shown in other royal tombs, normally appearing in burials of nobility.

Tomb WV22, also known as KV22, was the burial place of the Eighteenth Dynasty pharaoh Amenhotep III. Located in the Western arm of the Valley of the Kings, the tomb is unique in that it has two subsidiary burial chambers for the pharaoh's wives Tiye and Sitamen. It was officially discovered by Prosper Jollois and Édouard de Villiers du Terrage, engineers with Napoleon's expedition to Egypt in August 1799, but had probably been open for some time. The tomb was first excavated by Theodore M. Davis, the details of which are lost. The first documented clearance was carried out by Howard Carter in 1915. Since 1989, a Japanese team from Waseda University led by Sakuji Yoshimura and Jiro Kondo has excavated and conserved the tomb. The sarcophagus is missing from the tomb. The tomb's layout and decoration follow the tombs of the king's predecessors, Amenhotep II (KV35) and Thutmose IV (KV43); however, the decoration is much finer in quality. Several images of the pharaoh's head have been cut out and can be seen today in the Louvre.

Tomb KV35 is the tomb of Pharaoh Amenhotep II located in the Valley of the Kings in Luxor, Egypt. Later, it was used as a cache for other royal mummies. It was discovered by Victor Loret in March 1898.

KV20 is a tomb in the Valley of the Kings (Egypt). It was probably the first royal tomb to be constructed in the valley. KV20 was the original burial place of Thutmose I and later was adapted by his daughter Hatshepsut to accommodate her and her father. The tomb was known to Napoleon Bonaparte's expedition in 1799 and had been visited by several explorers between 1799 and 1903. A full clearance of the tomb was undertaken by Howard Carter in 1903–1904. KV20 is distinguishable from other tombs in the valley, both in its general layout and because of the atypical clockwise curvature of its corridors.

Tomb KV19, located in a side branch of Egypt's Valley of the Kings, was intended as the burial place of Prince Ramesses Sethherkhepshef, better known as Pharaoh Ramesses VIII, but was later used for the burial of Prince Mentuherkhepshef instead, the son of Ramesses IX, who predeceased his father. Though incomplete and used "as is," the decoration is considered to be of the highest quality.

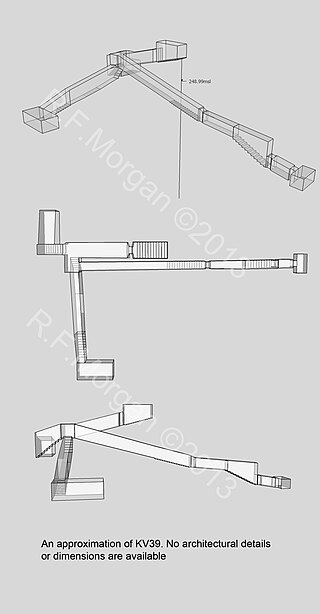

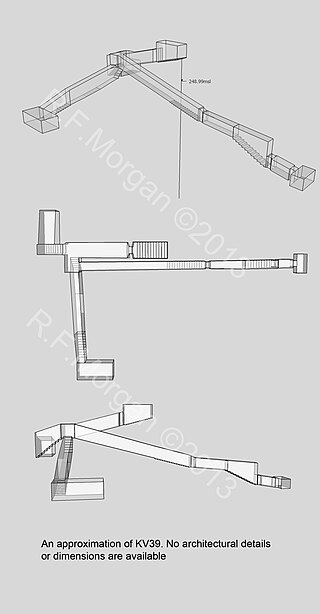

Tomb KV39 in Egypt's Valley of the Kings is one of the possible locations of the tomb of Pharaoh Amenhotep I. It is located high in the cliffs, away from the main valley bottom and other royal burials. It is in a small wadi that runs from the east side of Al-Qurn, directly under the ridge where the workmen's village of Deir el-Medina lies. The layout of the tomb is unique. It has two axes, one east and one south. Its construction seems to have occurred in three phases. It began as a simple straight axis tomb that never continued past the first room. In the subsequent phase, a series of long descending corridors and steps were cut to the east and south. It was discovered around 1900 by either Victor Loret or Macarious and Andraos but was not fully examined. It was excavated between 1989 and 1994 by John Rose and was further examined in 2002 by Ian Buckley. Based on the tomb's architecture and pottery found, it was likely cut in the early Eighteenth Dynasty, possibly for a queen. Fragmentary remains of burials were recovered from parts of the tomb but who they belong to is unknown. KV39's location may fit the description of the tomb of Amenhotep I given in the Abbott Papyrus but this is the subject of debate.

Thuya was an Egyptian noblewoman and the mother of queen Tiye, and the wife of Yuya. She is the grandmother of Akhenaten, and great grandmother of Tutankhamun.

The area of the Valley of the Kings, in Luxor, Egypt, has been a major area of modern Egyptological exploration for the last two centuries. Before this, the area was a site for tourism in antiquity. This area illustrates the changes in the study of ancient Egypt, beginning as antiquity hunting and ending with the scientific excavation of the whole Theban Necropolis. Despite the exploration and investigation noted below, only eleven of the tombs have actually been completely recorded.

Tomb KV57 is the royal tomb of Horemheb, the last pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty and is located in the Valley of the Kings, Egypt.

Tomb WV24 is an ancient Egyptian tomb located in the western arm of the Valley of the Kings. It was reported by Robert Hay and John Wilkinson in the 1820s and visited by Howard Carter; however, it was not fully explored until Otto Schaden's excavations in 1991.

KV44 is an ancient Egyptian tomb located in the Valley of the Kings, Egypt. It was discovered and excavated by Howard Carter in 1901 and was re-examined in 1991 by Donald P. Ryan. The single chamber accessed by a shaft contained three intact Twenty-second Dynasty burials; the remains of seven mummies from the original interment were found within the fill. The original cutting of the tomb is dated to the Eighteenth Dynasty.

Tomb KV21 is an ancient Egyptian tomb located in the Valley of the Kings in Egypt. It was discovered in 1817 by Giovanni Belzoni and later re-excavated by Donald P. Ryan in 1989. It contains the mummies of two women, thought to be Eighteenth Dynasty queens. In 2010, a team headed by Zahi Hawass used DNA evidence to tentatively identify one mummy, KV21A, as the biological mother of the two fetuses preserved in the tomb of King Tutankhamun.

KV31 is an ancient Egyptian tomb located in the Valley of the Kings, near Luxor, Egypt. Only the top of the shaft was known prior to excavation by the University of Basel Kings' Valley Project in 2010, and no earlier excavations are known, although it is suggested that the stone sarcophagus excavated by Giovanni Battista Belzoni in 1817 may have originated from this tomb. The tomb was found to be filled with mixed debris of pottery sherds and linen fragments, as well as the remains of five mummified elite individuals dating to the Eighteenth Dynasty.

Tomb KV58, known as the "Chariot Tomb", is located in the Valley of the Kings in Egypt. It was discovered in January 1909 by Harold Jones, excavating on behalf of Theodore M. Davis. The circumstances of the discovery and specifics of the excavation were only given a passing mention in Davis' account, who attributes the discovery to Edward Ayrton in 1907 instead. The tomb consists of a shaft leading to a single chamber and contained only embossed gold foil, furniture knobs, and a single ushabti. The contents likely originated from the Eighteenth Dynasty tomb of Ay in WV23. Davis considered this tomb to be the burial place of the then little-known pharaoh Tutankhamun.

The Valley of the Kings, also known as the Valley of the Gates of the Kings, is an area in Egypt where, for a period of nearly 500 years from the Eighteenth Dynasty to the Twentieth Dynasty, rock-cut tombs were excavated for pharaohs and powerful nobles under the New Kingdom of ancient Egypt.

The majority of the 65 numbered tombs in the Valley of the Kings can be considered minor tombs, either because at present they have yielded little information or because the results of their investigation was only poorly recorded by their explorers, while some have received very little attention or were only cursorily noted. Most of these tombs are small, often only consisting of a single burial chamber accessed by means of a shaft or a staircase with a corridor or a series of corridors leading to the chamber, but some are larger, multiple chambered tombs. These minor tombs served various purposes, some were intended for burials of lesser royalty or for private burials, some contained animal burials and others apparently never received a primary burial. In many cases these tombs also served secondary functions and later intrusive material has been found related to these secondary activities. While some of these tombs have been open since antiquity, the majority were discovered in the 19th and early 20th centuries during the height of exploration in the valley.