Related Research Articles

The Cree are a North American Indigenous people. They live primarily in Canada, where they form one of the country's largest First Nations.

The Métis are an Indigenous people whose historical homelands includes Canada's three Prairie Provinces, as well as parts of British Columbia, the Northwest Territories, Northwest Ontario and the Northern United States. They have a shared history and culture, deriving from specific mixed European and Indigenous ancestry, which became distinct through ethnogenesis by the mid-18th century, during the early years of the North American fur trade.

Treaty 6 is the sixth of the numbered treaties that were signed by the Canadian Crown and various First Nations between 1871 and 1877. It is one of a total of 11 numbered treaties signed between the Canadian Crown and First Nations. Specifically, Treaty 6 is an agreement between the Crown and the Plains and Woods Cree, Assiniboine, and other band governments at Fort Carlton and Fort Pitt. Key figures, representing the Crown, involved in the negotiations were Alexander Morris, Lieutenant Governor of the North-West Territories; James McKay, The Minister of Agriculture for Manitoba; and W.J. Christie, the Chief Factor of the Hudson's Bay Company. Chief Mistawasis and Chief Ahtahkakoop represented the Carlton Cree.

Harold Cardinal was a Cree writer, political leader, teacher, negotiator, and lawyer. Throughout his career he advocated, on behalf of all First Nation peoples, for the right to be "the red tile in the Canadian mosaic."

The George Gordon First Nation is a First Nations band government located near the village of Punnichy, Saskatchewan, in Canada. The nation has an enrolled population of 3,752 people, 1,191 of whom live on the band's reserves. Chief Byron Bitternose leads the First Nation. Their territory is located on the Gordon 86 reserve, as arranged by Treaty 4.

The Sweetgrass First Nation is a Cree First Nation reserve in Cut Knife, Saskatchewan, Canada. Their territory is located 35 kilometers west of Battleford. The reserve was established when Chief Sweetgrass signed Treaty 6 on September 9, 1876, with the Fort Pitt Indians. Chief Sweetgrass was killed six months after signing Treaty 6, after which Sweetgrass's son, Apseenes, succeeded him. Apseenes was unsuccessful in leading the band so chiefdom was handed over to Wah-wee-kah-oo-tah-mah-hote after he signed Treaty 6 in 1876 at Fort Carlton. Wah-wee-kah-oo-tah-mah-hote served as chief between 1876 and 1883 but was deposed and Apseenes took over chiefdom.

Noel Victor Starblanket was a Canadian politician. For two terms from 1976 to 1980 he was chief of the National Indian Brotherhood.

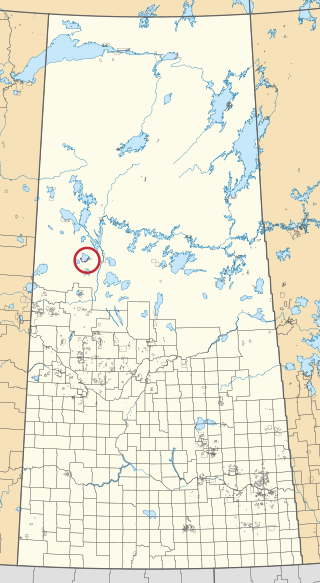

Canoe Lake 165 is an Indian reserve of the Canoe Lake Cree First Nation in the boreal forest of northern Saskatchewan, Canada. Its location is on Canoe Lake approximately thirty miles west of Beauval, within the ancient hunting grounds of the Woodland Cree. In the 2016 Canadian Census, it recorded a population of 912 living in 250 of its 273 total private dwellings. In the same year, its Community Well-Being index was calculated at 53 of 100, compared to 58.4 for the average First Nations community and 77.5 for the average non-Indigenous community. The reserve includes the settlement of Canoe Narrows. The name of the reserve and the settlement in Cree is nêhiyaw-wapâsihk ᓀᐦᐃᔭᐤ ᐘᐹᓯᕽ.

Mary Ellen Elizabeth Turpel-Lafond is a Canadian lawyer, former judge, and legislative advocate for children's rights.

Cowessess First Nation is a Saulteaux First Nations band government in southern Saskatchewan, Canada. The band's main reserve is Cowessess 73, one of several adjoining Indigenous communities in the Qu'Appelle Valley. The band also administers Cowessess 73A, near Esterhazy, and Treaty Four Reserve Grounds 77, which is shared with 32 other bands.

Tracey Lindberg is a writer, scholar, lawyer and Indigenous Rights activist from the Kelly Lake Cree Nation in British Columbia. She is Cree-Métis and a member of the As'in'i'wa'chi Ni'yaw Nation Rocky Mountain Cree.

Marion Ironquill Meadmore is an Ojibwa-Cree Canadian activist and lawyer. Meadmore was the first woman of the First Nations to attain a law degree in Canada. She founded the first Indian and Métis Friendship Centre in Canada to assist indigenous people who had relocated to urban areas with adjustments to their new communities. She edited the native newspaper The Prairie Call, bringing cultural events as well as socio-economic challenges into discussion for native communities. She was the only woman on the Temporary Committee of the National Indian Council, which would later become the Assembly of First Nations, and would become the secretary-treasurer of the organization when it was formalized. She was one of the women involved in the launch of the Kinew Housing project, to bring affordable, safe housing to indigenous urban dwellers and a founder of the Indigenous Bar Association of Canada. She has received the Order of Canada as well as many other honors for her activism on behalf of indigenous people. She was a founder and currently serves on the National Indigenous Council of Elders.

Judy Anderson is a Nêhiyaw Cree artist from the Gordon First Nation in Saskatchewan, Canada, which is a Treaty 4 territory. Anderson is currently an Associate Professor of Canadian Indigenous Studio Art in the Department of Arts at the University of Calgary. Her artwork focuses on issues of spirituality, colonialism, family, and Indigeneity and she uses in her practice hand-made paper, beadwork, painting, and does collaborative projects, such as the ongoing collaboration with her son Cruz, where the pair combine traditional Indigenous methodologies and graffiti. Anderson has also been researching traditional European methods and materials of painting.

Michael Linklater is a retired Canadian basketball player. He last played for the Saskatchewan Rattlers in the Canadian Elite Basketball League (CEBL). He is a Nehiyaw (Cree). Linklater received the 2018 Tom Longboat Award, which recognizes Aboriginal athletes "for their outstanding contributions to sport in Canada". He won the 2018 Inspire Award in the sports category.

Sylvia McAdam Saysewahum is a member of the Cree Nation. She is an advocate for First Nation and environmental rights in Canada. She is a founding member of Idle No More, a lawyer, a professor, and an author. In all of these cases, her work is focused on spreading awareness and education about First Nation and Environmental rights.

Indigenous law in Canada refers to the legal traditions, customs, and practices of Indigenous peoples and groups. Canadian aboriginal law is different from Indigenous Law. Canadian Aboriginal law provides certain constitutionally recognized rights to land and traditional practices.

Birdie is the 2015 debut novel of Indigenous Canadian author Tracey Lindberg. It was first published in hardback on May 26, 2015 by HarperCollins Publishers. Upon its release it was named a CBC Canada Reads Finalist, OLA Evergreen Award and a KOBO Emerging Writer Prize. The book is known for its inclusion of Cree Law and its commentary on Canadian Colonialism.

Lisa Bird-Wilson is a Métis and nêhiyaw writer from Saskatchewan.

Criminal sentencing in Canada is governed by the Canadian Criminal Code. The Criminal Code, along with the Supreme Court of Canada, have distinguished the treatment of Indigenous individuals within the Canadian Criminal Sentencing Regime.

Belinda kakiyosēw Daniels is a nēhiyaw Canadian educator and language activist known for efforts to teach and revitalize nēhiyawēwin.

References

- 1 2 Lindberg, Darcy (2020). "Nêhiyaw Âskiy Wiyasiwêwina: Plains Cree Earth Law and constitutional/ecological reconciliation". Canada: University of Victoria. p. 40. Retrieved 2021-11-17.

- 1 2 Snyder E, Napoleon V, Borrows J (2015). "Gender and Violence: Drawing on Indigenous Legal Resources" (PDF). UNC Law Review. 48: 800. Retrieved 2018-07-23.

- 1 2 3 4 Flaminio, Anna Louisa (2013). Gladue through Wahkohtowin: Social History Through Cree Kinship Lens in Corrections and Parole (LLM Thesis). University of Saskatchewan College of Law [unpublished]. pp. 18–26. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.842.2573 .

- ↑ Borrows J (2010). Canada's Indigenous Constitution. Beilen: University of Toronto Press. p. 24. ISBN 9781442698529.

- 1 2 Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (2015). Canada's Residential Schools: Reconciliation: The Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Volume 6 (Report). McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 58–59.

- ↑ Napoleon V (2007). "Thinking about Indigenous Legal Orders" (PDF). National Centre for First Nations Governance. 1 (1): 15. Retrieved 2018-07-24.

- ↑ Lindberg, Darcy (2018-01-01). "Miyo Nehiyawiwin : Ceremonial Aesthetics and Nehiyaw Legal Pedagogy". Indigenous Law Journal at the University of Toronto, Faculty of Law. 16: 51–65. ISSN 1703-4566.

- ↑ Buhler, Sarah (2017). "Reading Law and Imagining Justice in the Wahkohtowin Classroom". Windsor Yearbook of Access to Justice. 34 (1): 175–188. doi:10.22329/wyaj.v34i1.5011. ISSN 2561-5017. S2CID 148767988 . Retrieved 2023-11-10.