Tribal sovereignty in the United States is the concept of the inherent authority of indigenous tribes to govern themselves within the borders of the United States. Originally, the U.S. federal government recognized American Indian tribes as independent nations, and came to policy agreements with them via treaties. As the U.S. accelerated its westward expansion, internal political pressure grew for "Indian removal", but the pace of treaty-making grew nevertheless. The Civil War forged the U.S. into a more centralized and nationalistic country, fueling a "full bore assault on tribal culture and institutions", and pressure for Native Americans to assimilate. In the Indian Appropriations Act of 1871, Congress prohibited any future treaties. This move was steadfastly opposed by Native Americans. Currently, the U.S. recognizes tribal nations as "domestic dependent nations" and uses its own legal system to define the relationship between the federal, state, and tribal governments.

Public Law 280, is a federal law of the United States establishing "a method whereby States may assume jurisdiction over reservation Indians," as stated in McClanahan v. Arizona State Tax Commission. 411 U.S. 164, 177 (1973).

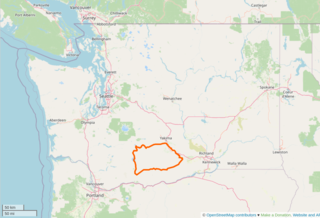

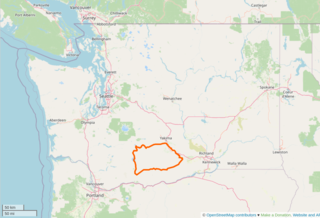

The Yakama Indian Reservation is a Native American reservation in Washington state of the federally recognized tribe known as the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation. The tribe is made up of Klikitat, Palus, Wallawalla, Wanapam, Wenatchi, Wishram, and Yakama peoples.

Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe, 435 U.S. 191 (1978), is a United States Supreme Court case deciding that Indian tribal courts have no criminal jurisdiction over non-Indians. The case was decided on March 6, 1978 with a 6–2 majority. The court opinion was written by William Rehnquist, and a dissenting opinion was written by Thurgood Marshall, who was joined by Chief Justice Warren Burger. Justice William J. Brennan did not participate in the decision.

United States v. Washington, 384 F. Supp. 312, aff'd, 520 F.2d 676, commonly known as the Boldt Decision, was a legal case in 1974 heard in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Washington and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. The case re-affirmed the rights of American Indian tribes in the state of Washington to co-manage and continue to harvest salmon and other fish under the terms of various treaties with the U.S. government. The tribes ceded their land to the United States but reserved the right to fish as they always had. This included their traditional locations off the designated reservations.

Seminole Tribe of Florida v. Florida, 517 U.S. 44 (1996), was a United States Supreme Court case which held that Article One of the U.S. Constitution did not give the United States Congress the power to abrogate the sovereign immunity of the states that is further protected under the Eleventh Amendment. Such abrogation is permitted where it is necessary to enforce the rights of citizens guaranteed under the Fourteenth Amendment as per Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer. The case also held that the doctrine of Ex parte Young, which allows state officials to be sued in their official capacity for prospective injunctive relief, was inapplicable under these circumstances, because any remedy was limited to the one that Congress had provided.

Duro v. Reina, 495 U.S. 676 (1990), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court concluded that Indian tribes could not prosecute Indians who were members of other tribes for crimes committed by those nonmember Indians on their reservations. The decision was not well received by the tribes, because it defanged their criminal codes by depriving them of the power to enforce them against anyone except their own members. In response, Congress amended a section of the Indian Civil Rights Act, 25 U.S.C. § 1301, to include the power to "exercise criminal jurisdiction over all Indians" as one of the powers of self-government.

Indian termination is a phrase describing United States policies relating to Native Americans from the mid-1940s to the mid-1960s. It was shaped by a series of laws and practices with the intent of assimilating Native Americans into mainstream American society. Cultural assimilation of Native Americans was not new; the belief that indigenous people should abandon their traditional lives and become what the government considers "civilized" had been the basis of policy for centuries. What was new, however, was the sense of urgency that, with or without consent, tribes must be terminated and begin to live "as Americans." To that end, Congress set about ending the special relationship between tribes and the federal government.

United States v. Winans, 198 U.S. 371 (1905), was a U.S. Supreme Court case that held that the Treaty with the Yakima of 1855, negotiated and signed at the Walla Walla Council of 1855, as well as treaties similar to it, protected the Indians' rights to fishing, hunting and other privileges.

Nevada v. Hicks, 533 U.S. 353 (2001), is a United States Supreme Court case regarding the jurisdiction of Tribal Courts when state officials are sued by tribal members in tribal court. The Supreme Court unanimously decided that Tribal courts lack jurisdiction to decide tort claims or § 1983 claims related to State law enforcement's process on the reservation, but related to a crime that allegedly occurred off the reservation nor must the parties exhaust their claims in Tribal court before filing in federal court.

California v. Cabazon Band of Mission Indians, 480 U.S. 202 (1987), was a United States Supreme Court case involving the development of Native American gaming. The Supreme Court's decision effectively overturned the existing laws restricting gaming/gambling on U.S. Indian reservations.

United States v. Lara, 541 U.S. 193 (2004), was a United States Supreme Court landmark case which held that both the United States and a Native American (Indian) tribe could prosecute an Indian for the same acts that constituted crimes in both jurisdictions. The Court held that the United States and the tribe were separate sovereigns; therefore, separate tribal and federal prosecutions did not violate the Double Jeopardy Clause.

Menominee Tribe v. United States, 391 U.S. 404 (1968), is a case in which the Supreme Court ruled that the Menominee Indian Tribe kept their historical hunting and fishing rights even after the federal government ceased to recognize the tribe. It was a landmark decision in Native American case law.

South Dakota v. Bourland, 508 U.S. 679 (1993), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that Congress specifically abrogated treaty rights with the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe as to hunting and fishing rights on reservation lands that were acquired for a reservoir.

Bryan v. Itasca County, 426 U.S. 373 (1976), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that a state did not have the right to assess a tax on the property of a Native American (Indian) living on tribal land absent a specific Congressional grant of authority to do so.

Merrion v. Jicarilla Apache Tribe, 455 U.S. 130 (1982), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States holding that an Indian tribe has the authority to impose taxes on non-Indians that are conducting business on the reservation as an inherent power under their tribal sovereignty.

Oklahoma Tax Commission v. Sac & Fox Nation, 508 U.S. 114 (1993), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that absent explicit congressional direction to the contrary, it must be presumed that a State does not have jurisdiction to tax tribal members who live and work in Indian country, whether the particular territory consists of a formal or informal reservation, allotted lands, or dependent Indian communities.

United States v. John, 437 U.S. 634 (1978), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that lands designated as a reservation in Mississippi are "Indian country" as defined by statute, although the reservation was established nearly a century after Indian removal and related treaties. The court ruled that, under the Major Crimes Act, the State has no jurisdiction to try a Native American for crimes covered by that act that occurred on reservation land.

United States v. Antelope, 430 U.S. 641 (1977), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held that American Indians convicted on reservation land were not deprived of the equal protection of the laws; (a) the federal criminal statutes are not based on impermissible racial classifications but on political membership in an Indian tribe or nation; and (b) the challenged statutes do not violate equal protection. Indians or non-Indians can be charged with first-degree murder committed in a federal enclave.

Washington State Dep't of Licensing v. Cougar Den, Inc., 586 U.S. ___ (2019), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held that the Yakama Nation Treaty of 1855 preempts the state law which the State purported to be able to tax fuel purchased by a tribal corporation for sale to tribal members. This was a 5-4 plurality decision, with Justice Breyer's opinion being joined by Justices Sotomayor and Kagan. Justice Gorsuch, joined by Justice Ginsburg, penned a concurring opinion. There were dissenting opinions by Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Kavanaugh.