| Bryan v. Itasca County | |

|---|---|

| |

| Argued April 20, 1976 Decided June 14, 1976 | |

| Full case name | Russell Bryan v. Itasca County, Minnesota |

| Citations | 426 U.S. 373 ( more ) 96 S. Ct. 2102; 48 L. Ed. 2d 710; 1976 U.S. LEXIS 61 |

| Case history | |

| Prior | Bryan v. Itasca County, 228N.W.2d249 (Minn.1975). |

| Holding | |

| Minnesota did not have the right to assess a tax on the property of an Indian living on tribal land absent a specific Congressional grant of authority to do so | |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinion | |

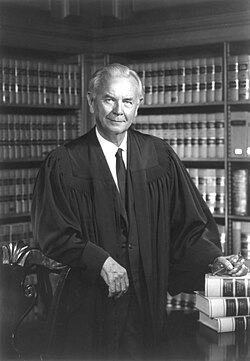

| Majority | Brennan, joined by unanimous |

| Laws applied | |

| 28 U.S.C. § 1360 | |

Bryan v. Itasca County, 426 U.S. 373 (1976), was a landmark case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that a state did not have the right to assess a tax on the property of a Native American (Indian) living on tribal land absent a specific Congressional grant of authority to do so.

Contents

- Background

- Background information

- History

- Lower courts

- Opinion of the Court

- Arguments

- Unanimous opinion

- Subsequent developments

- References

- External links

The case arose when a Minnesota county taxed an Ojibwe couple's mobile home located on a reservation. The Court ruled that the state did not have the authority to impose such a tax or, more generally, to regulate behavior on the reservation. Bryan has become a landmark case that has led to Indian gaming on reservations and altered the economic status of almost every Indian tribe. Later decisions, citing Bryan, ruled that Public Law 280 allows states to enact prohibitions, or crimes, that would apply on reservations, but could not impose regulations on conduct that was otherwise allowed. The case has also called into question the ability of the states to impose any sort of regulations on tribal reservations, such as labor standards and certain traffic regulations. [1]