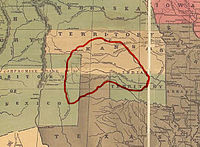

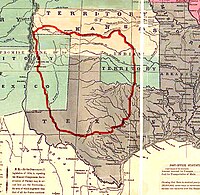

Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States government for the relocation of Native Americans who held original Indian title to their land as a sovereign independent state. The concept of an Indian territory was an outcome of the U.S. federal government's 18th- and 19th-century policy of Indian removal. After the American Civil War (1861–1865), the policy of the U.S. government was one of assimilation.

Kiowa or Ka'igwa people are a Native American tribe and an indigenous people of the Great Plains of the United States. They migrated southward from western Montana into the Rocky Mountains in Colorado in the 17th and 18th centuries, and eventually into the Southern Plains by the early 19th century. In 1867, the Kiowa were moved to a reservation in southwestern Oklahoma.

The Medicine Lodge Treaty is the overall name for three treaties signed near Medicine Lodge, Kansas, between the Federal government of the United States and southern Plains Indian tribes in October 1867, intended to bring peace to the area by relocating the Native Americans to reservations in Indian Territory and away from European-American settlement. The treaty was negotiated after investigation by the Indian Peace Commission, which in its final report in 1868 concluded that the wars had been preventable. They determined that the United States government and its representatives, including the United States Congress, had contributed to the warfare on the Great Plains by failing to fulfill their legal obligations and to treat the Native Americans with honesty.

Tribal sovereignty in the United States is the concept of the inherent authority of Indigenous tribes to govern themselves within the borders of the United States.

The Sac and Fox Nation is the largest of three federally recognized tribes of Sauk and Meskwaki (Fox) Indian peoples. Originally from the Lake Huron and Lake Michigan area, they were forcibly relocated to Oklahoma in the 1870s and are predominantly Sauk. The Sac and Fox Oklahoma Tribal Statistical Area (OTSA) is the land base in Oklahoma governed by the tribe.

An American Indian reservation is an area of land held and governed by a U.S. federal government-recognized Native American tribal nation, whose government is sovereign, subject to regulations passed by the United States Congress and administered by the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs, and not to the U.S. state government in which it is located. Some of the country's 574 federally recognized tribes govern more than one of the 326 Indian reservations in the United States, while some share reservations, and others have no reservation at all. Historical piecemeal land allocations under the Dawes Act facilitated sales to non–Native Americans, resulting in some reservations becoming severely fragmented, with pieces of tribal and privately held land being treated as separate enclaves. This jumble of private and public real estate creates significant administrative, political, and legal difficulties.

The Red River War was a military campaign launched by the United States Army in 1874 to displace the Comanche, Kiowa, Southern Cheyenne, and Arapaho tribes from the Southern Plains, and forcibly relocate the tribes to reservations in Indian Territory. The war had several army columns crisscross the Texas Panhandle in an effort to locate, harass, and capture nomadic Native American bands. Most of the engagements were small skirmishes with few casualties on either side. The war wound down over the last few months of 1874, as fewer and fewer Indian bands had the strength and supplies to remain in the field. Though the last significantly sized group did not surrender until mid-1875, the war marked the end of free-roaming Indian populations on the southern Great Plains.

Seminole Tribe of Florida v. Florida, 517 U.S. 44 (1996), was a United States Supreme Court case which held that Article One of the U.S. Constitution did not give the United States Congress the power to abrogate the sovereign immunity of the states that is further protected under the Eleventh Amendment. Such abrogation is permitted where it is necessary to enforce the rights of citizens guaranteed under the Fourteenth Amendment as per Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer. The case also held that the doctrine of Ex parte Young, which allows state officials to be sued in their official capacity for prospective injunctive relief, was inapplicable under these circumstances, because any remedy was limited to the one that Congress had provided.

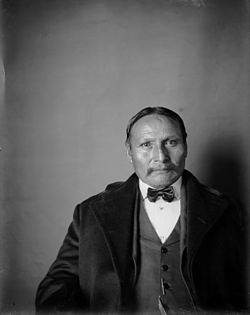

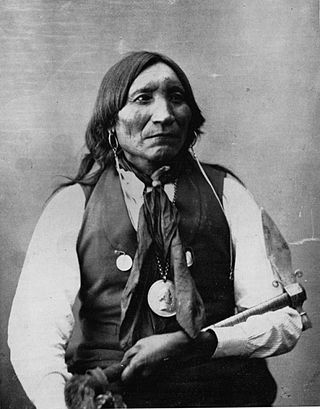

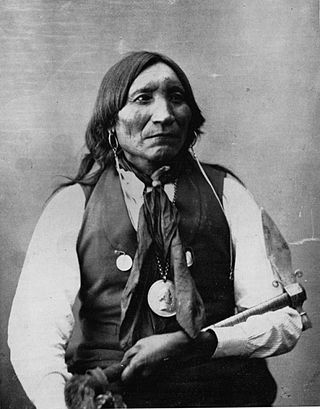

Lone Wolf the Younger, also known as Gui-pah-gho the Younger, or the Elk Creek Lone Wolf was a Kiowa and warrior originally named Mamay-day-te.After a raid he was given the name Gui-pah-gho by Gui-pah-gho the Elder after avenging the death of Tau-ankia, the only son of Gui-pah-gho the Elder. Mamay-day-te participated in a raid avenging deaths and counted his first coup during the attack. Lone Wolf the Younger led the Kiowa resistance to United States governmental influence on the reservation, which culminated in the Supreme Court case Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock.

William McKendree Springer was a United States Representative from Illinois.

The Omaha Reservation of the federally recognized Omaha tribe is located mostly in Thurston County, Nebraska, with sections in neighboring Cuming and Burt counties, in addition to Monona County in Iowa. As of the 2020 federal census, the reservation population was 4,526. The tribal seat of government is in Macy. The villages of Rosalie, Pender and Walthill are located within reservation boundaries, as is the northernmost part of Bancroft. Due to land sales in the area since the reservation was established, Pender has disputed tribal jurisdiction over it, to which the Supreme Court ruled unanimously in 2016 that "the disputed land is within the reservation’s boundaries."

The Indian Peace Commission was a group formed by an act of Congress on July 20, 1867 "to establish peace with certain hostile Indian tribes." It was composed of four civilians and three, later four, military leaders. Throughout 1867 and 1868, they negotiated with a number of tribes, including the Comanche, Kiowa, Arapaho, Kiowa-Apache, Cheyenne, Lakota, Navajo, Snake, Sioux, and Bannock. The treaties that resulted were designed to move the tribes to reservations, to "civilize" and assimilate these native peoples, and transition their societies from a nomadic to an agricultural existence.

Menominee Tribe v. United States, 391 U.S. 404 (1968), is a case in which the Supreme Court ruled that the Menominee Indian Tribe kept their historical hunting and fishing rights even after the federal government ceased to recognize the tribe. It was a landmark decision in Native American case law.

Ex parte Crow Dog, 109 U.S. 556 (1883), is a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States that followed the death of one member of a Native American tribe at the hands of another on reservation land. Crow Dog was a member of the Brulé band of the Lakota Sioux. On August 5, 1881 he shot and killed Spotted Tail, a Lakota chief; there are different accounts of the background to the killing. The tribal council dealt with the incident according to Sioux tradition, and Crow Dog paid restitution to the dead man's family. However, the U.S. authorities then prosecuted Crow Dog for murder in a federal court. He was found guilty and sentenced to hang.

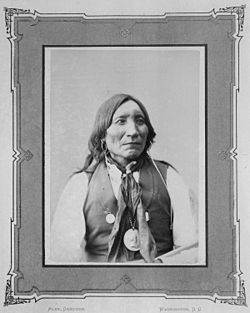

Guipago or Lone Wolf the Elder was the last Principal Chief of the Kiowa tribe. He was a member of the Koitsenko, the Kiowa warrior elite, and was a signer of the Little Arkansas Treaty in 1865.

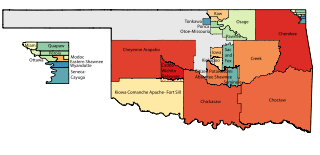

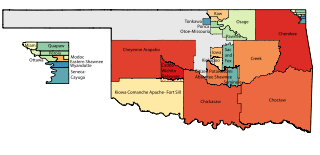

Oklahoma Tribal Statistical Area is a statistical entity identified and delineated by federally recognized American Indian tribes in Oklahoma as part of the U.S. Census Bureau's 2010 Census and ongoing American Community Survey. Many of these areas are also designated Tribal Jurisdictional Areas, areas within which tribes will provide government services and assert other forms of government authority. They differ from standard reservations, such as the Osage Nation of Oklahoma, in that allotment was broken up and as a consequence their residents are a mix of native and non-native people, with only tribal members subject to the tribal government. At least five of these areas, those of the so-called five civilized tribes of Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek and Seminole, which cover 43% of the area of the state, are recognized as reservations by federal treaty, and thus not subject to state law or jurisdiction for tribal members.

The Cherokee Commission, was a three-person bi-partisan body created by President Benjamin Harrison to operate under the direction of the Secretary of the Interior, as empowered by Section 14 of the Indian Appropriations Act of March 2, 1889. Section 15 of the same Act empowered the President to open land for settlement. The Commission's purpose was to legally acquire land occupied by the Cherokee Nation and other tribes in the Oklahoma Territory for non-indigenous homestead acreage.

An Organic Act is a generic name for a statute used by the United States Congress to describe a territory, in anticipation of being admitted to the Union as a state. Because of Oklahoma's unique history an explanation of the Oklahoma Organic Act needs a historic perspective. In general, the Oklahoma Organic Act may be viewed as one of a series of legislative acts, from the time of Reconstruction, enacted by Congress in preparation for the creation of a united State of Oklahoma. The Organic Act created Oklahoma Territory, and Indian Territory that were Organized incorporated territories of the United States out of the old "unorganized" Indian Territory. The Oklahoma Organic Act was one of several acts whose intent was the assimilation of the tribes in Oklahoma and Indian Territories through the elimination of tribes' communal ownership of property.

Sharp v. Murphy, 591 U.S. ___ (2020), was a Supreme Court of the United States case of whether Congress disestablished the Muscogee (Creek) Nation reservation. After holding the case from the 2018 term, the case was decided on July 9, 2020, in a per curiam decision following McGirt v. Oklahoma that, for the purposes of the Major Crimes Act, the reservations were never disestablished and remain Native American country.

Cherokee Nation v. Hitchcock, 187 U.S. 294 (1902) was a US Supreme Court case that decided the US Congress has the right to pass legislation that controls the actions and property of tribal states without their consent. The Cherokee Nation brought this case against the Secretary of the Interior because the Secretary authorized mineral and oil leases on Cherokee land, an action Congress had authorized by legislation. The Cherokee Nation argued that this action violated the treaty rights promised by the US to their Indian nation. In their decision, the Court stated this was out of the Court’s power as it was a question for the legislative branch to determine, not the judicial.