Tribal sovereignty in the United States is the concept of the inherent authority of indigenous tribes to govern themselves within the borders of the United States. Originally, the U.S. federal government recognized American Indian tribes as independent nations, and came to policy agreements with them via treaties. As the U.S. accelerated its westward expansion, internal political pressure grew for "Indian removal", but the pace of treaty-making grew nevertheless. The Civil War forged the U.S. into a more centralized and nationalistic country, fueling a "full bore assault on tribal culture and institutions", and pressure for Native Americans to assimilate. In the Indian Appropriations Act of 1871, without any input from Native Americans, Congress prohibited any future treaties. This move was steadfastly opposed by Native Americans. Currently, the U.S. recognizes tribal nations as "domestic dependent nations" and uses its own legal system to define the relationship between the federal, state, and tribal governments.

The Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, also called Pine Ridge Agency, is an Oglala Lakota Indian reservation located virtually entirely in the U.S. state of South Dakota. Originally included within the territory of the Great Sioux Reservation, Pine Ridge was created by the Act of March 2, 1889, 25 Stat. 888. in the southwest corner of South Dakota on the Nebraska border. Today it consists of 3,468.85 sq mi (8,984 km2) of land area and is one of the largest reservations in the United States.

Public Law 280, is a federal law of the United States establishing "a method whereby States may assume jurisdiction over reservation Indians," as stated in McClanahan v. Arizona State Tax Commission. 411 U.S. 164, 177 (1973).

Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe, 435 U.S. 191 (1978), is a United States Supreme Court case deciding that Indian tribal courts have no criminal jurisdiction over non-Indians. The case was decided on March 6, 1978 with a 6–2 majority. The court opinion was written by William Rehnquist, and a dissenting opinion was written by Thurgood Marshall, who was joined by Chief Justice Warren Burger. Justice William J. Brennan did not participate in the decision.

The Nonintercourse Act is the collective name given to six statutes passed by the Congress in 1790, 1793, 1796, 1799, 1802, and 1834 to set Amerindian boundaries of reservations. The various Acts were also intended to regulate commerce between settlers and the natives. The most notable provisions of the Act regulate the inalienability of aboriginal title in the United States, a continuing source of litigation for almost 200 years. The prohibition on purchases of Indian lands without the approval of the federal government has its origins in the Royal Proclamation of 1763 and the Confederation Congress Proclamation of 1783.

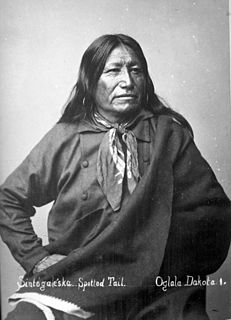

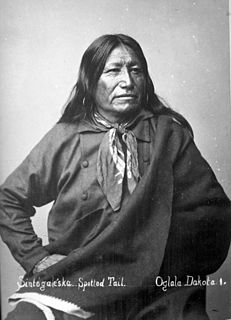

Spotted Tail ; born c. 1823 – died August 5, 1881) was a Brulé Lakota tribal chief. Although a great warrior in his youth, and having taken part in the Grattan massacre, he declined to participate in Red Cloud's War. He had become convinced of the futility of opposing the white incursions into his homeland; he became a statesman, speaking for peace and defending the rights of his tribe.

United States v. Kagama, 118 U.S. 375 (1886), was a United States Supreme Court case that upheld the constitutionality of the Major Crimes Act of 1885. This Congressional act gave the federal courts jurisdiction in certain Indian-on-Indian crimes, even if they were committed on an Indian reservation. Kagama, a Yurok Native American (Indian) accused of murder, was selected as a test case by the Department of Justice to test the constitutionality of the Act.

The Major Crimes Act is a law passed by the United States Congress in 1885 as the final section of the Indian Appropriations Act of that year. The law places certain crimes under federal jurisdiction if they are committed by a Native American in Native territory. The law follows the 1817 General Crimes Act, which extended federal jurisdiction to crimes committed in Native territory but did not cover crimes committed by Native Americans against Native Americans. The Major Crimes Act therefore broadened federal jurisdiction in Native territory by extending it to some crimes committed by Native Americans against Native Americans. The Major Crimes Act was passed by Congress in response to the Supreme Court of the United States's ruling in Ex parte Crow Dog that overturned the federal court conviction of Brule Lakota sub-chief Crow Dog for the murder of principal chief Spotted Tail on the Rosebud Indian Reservation.

Montana v. United States, 450 U.S. 544 (1981), was a Supreme Court case that addressed two issues: (1) Whether the title of the Big Horn Riverbed rested with the United States, in trust for the Crow Nation or passed to the State of Montana upon becoming a state and (2) Whether Crow Nation retained the power to regulate hunting and fishing on tribal lands owned in fee-simple by a non-tribal member. First, the Court held that Montana held title to the Big Horn Riverbed because the Equal Footing Doctrine required the United States to pass title to the newly incorporated State. Second, the Court held that Crow Nation lacked the power to regulate nonmember hunting and fishing on fee-simple land owned by nonmembers, but within the bounds of its reservation. More broadly, the Court held that Tribes could not exercise regulatory authority over nonmembers on fee-simple land within the reservation unless (1) the nonmember entered a "consensual relationship" with the Tribe or its members or (2) the nonmember's "conduct threatens or has some direct effect on the political integrity, the economic security, or the health or welfare of the tribe."

United States v. Lara, 541 U.S. 193 (2004), was a United States Supreme Court landmark case which held that both the United States and a Native American (Indian) tribe could prosecute an Indian for the same acts that constituted crimes in both jurisdictions. The Court held that the United States and the tribe were separate sovereigns; therefore, separate tribal and federal prosecutions did not violate the Double Jeopardy Clause.

Crow Dog was a Brulé Lakota subchief, born at Horse Stealing Creek, Montana Territory.

The United States was the first jurisdiction to acknowledge the common law doctrine of aboriginal title. Native American tribes and nations establish aboriginal title by actual, continuous, and exclusive use and occupancy for a "long time." Individuals may also establish aboriginal title, if their ancestors held title as individuals. Unlike other jurisdictions, the content of aboriginal title is not limited to historical or traditional land uses. Aboriginal title may not be alienated, except to the federal government or with the approval of Congress. Aboriginal title is distinct from the lands Native Americans own in fee simple and occupy under federal trust.

Ex parte Crow Dog, 109 U.S. 556 (1883), is a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States that followed the death of one member of a Native American tribe at the hands of another on reservation land. Crow Dog was a member of the Brulé band of the Lakota Sioux. On August 5, 1881 he shot and killed Spotted Tail, a Lakota chief; there are different accounts of the background to the killing. The tribal council dealt with the incident according to Sioux tradition, and Crow Dog paid restitution to the dead man's family. However, the U.S. authorities then prosecuted Crow Dog for murder in a federal court. He was found guilty and sentenced to hang.

Iron Crow v. Oglala Sioux Tribe of Pine Ridge Reservation, 231 F.2d 89, was a case where the plaintiffs challenged the authority of Indian tribal courts. The case, involving both adultery and tax assessment, was heard by the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit.

New Mexico v. Mescalero Apache Tribe, 462 U.S. 324 (1983), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that the application of New Mexico's laws to on-reservation hunting and fishing by nonmembers of the Tribe is preempted by the operation of federal law.

Idaho v. United States, 533 U.S. 262 (2001), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held that the United States, not the state of Idaho, held title to lands submerged under Lake Coeur d'Alene and the St. Joe River, and that the land was held in trust for the Coeur d'Alene Tribe as part of its reservation, and in recognition of the importance of traditional tribal uses of these areas for basic food and other needs.

United States v. John, 437 U.S. 634 (1978), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that lands designated as a reservation in Mississippi are "Indian country" as defined by statute, although the reservation was established nearly a century after Indian removal and related treaties. The court ruled that, under the Major Crimes Act, the State has no jurisdiction to try a Native American for crimes covered by that act that occurred on reservation land.

United States v. Ramsey, 271 U.S. 467 (1926), was a U.S. Supreme Court case in which the Court held that the government had the authority to prosecute crimes against Native Americans (Indians) on reservation land that was still designated Indian Country by federal law. The Osage Indian Tribe held mineral rights that were worth millions of dollars. A white rancher, William K. Hale, devised a plot to kill tribal members to allow his nephew, who was married to a tribal member, to inherit the mineral rights. The tribe requested the assistance of the federal government, which sent Bureau of Investigation agents to solve the murders. Hale and several others were arrested and tried for the murders, but they claimed that the federal government did not have jurisdiction. The district court quashed the indictments, but on appeal, the Supreme Court reversed, holding that the Osage lands were Indian Country and that the federal government therefore had jurisdiction. This put an end to the Osage Indian murders.

Sharp v. Murphy, 591 U.S. ___ (2020), was a Supreme Court of the United States case of whether Congress disestablished the Muscogee (Creek) Nation reservation. After holding the case from the 2018 term, the case was decided on July 9, 2020, in a per curiam decision following McGirt v. Oklahoma that, for the purposes of the Major Crimes Act, the reservations were never disestablished and remain Native American country.