Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content in contrast to that of cast iron. It is a semi-fused mass of iron with fibrous slag inclusions, which give it a wood-like "grain" that is visible when it is etched, rusted, or bent to failure. Wrought iron is tough, malleable, ductile, corrosion resistant, and easily forge welded, but is more difficult to weld electrically.

Ashdown Forest is an ancient area of open heathland occupying the highest sandy ridge-top of the High Weald Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. It is situated some 30 miles (48 km) south of London in the county of East Sussex, England. Rising to an elevation of 732 feet (223 m) above sea level, its heights provide expansive vistas across the heavily wooded hills of the Weald to the chalk escarpments of the North Downs and South Downs on the horizon.

A blast furnace is a type of metallurgical furnace used for smelting to produce industrial metals, generally pig iron, but also others such as lead or copper. Blast refers to the combustion air being supplied above atmospheric pressure.

Bog iron is a form of impure iron deposit that develops in bogs or swamps by the chemical or biochemical oxidation of iron carried in solution. In general, bog ores consist primarily of iron oxyhydroxides, commonly goethite.

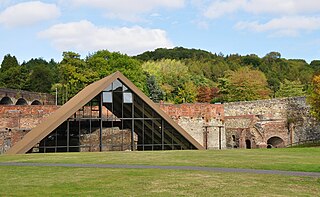

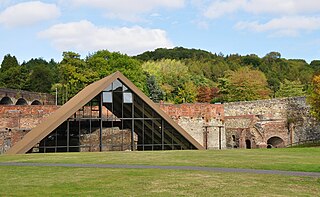

Coalbrookdale is a village in the Ironbridge Gorge and the Telford and Wrekin borough of Shropshire, England, containing a settlement of great significance in the history of iron ore smelting. It lies within the civil parish called the Gorge.

A bloomery is a type of metallurgical furnace once used widely for smelting iron from its oxides. The bloomery was the earliest form of smelter capable of smelting iron. Bloomeries produce a porous mass of iron and slag called a bloom. The mix of slag and iron in the bloom, termed sponge iron, is usually consolidated and further forged into wrought iron. Blast furnaces, which produce pig iron, have largely superseded bloomeries.

An ironworks or iron works is an industrial plant where iron is smelted and where heavy iron and steel products are made. The term is both singular and plural, i.e. the singular of ironworks is ironworks.

Buxted is a village and civil parish in the Wealden district of East Sussex in England. The parish is situated on the Weald, north of Uckfield; the settlements of Five Ash Down, Heron's Ghyll and High Hurstwood are included within its boundaries. At one time its importance lay in the Wealden iron industry, and later it became commercially important in the poultry and egg industry.

Puddling is the process of converting pig iron to bar (wrought) iron in a coal fired reverberatory furnace. It was developed in England during the 1780s. The molten pig iron was stirred in a reverberatory furnace, in an oxidizing environment to burn the carbon, resulting in wrought iron. It was one of the most important processes for making the first appreciable volumes of valuable and useful bar iron without the use of charcoal. Eventually, the furnace would be used to make small quantities of specialty steels.

A hammer mill, hammer forge or hammer works was a workshop in the pre-industrial era that was typically used to manufacture semi-finished, wrought iron products or, sometimes, finished agricultural or mining tools, or military weapons. The feature that gave its name to these workshops was the water-driven trip hammer, or set of hammers, used in the process. The shaft, or 'helve', of the hammer was pivoted in the middle and the hammer head was lifted by the action of cams set on a rotating camshaft that periodically depressed the end of the shaft. As it rose and fell, the head of the hammer described an arc. The face of the hammer was made of iron for durability.

A finery forge is a forge used to produce wrought iron from pig iron by decarburization in a process called "fining" which involved liquifying cast iron in a fining hearth and removing carbon from the molten cast iron through oxidation. Finery forges were used as early as the 3rd century BC in China. The finery forge process was replaced by the puddling process and the roller mill, both developed by Henry Cort in 1783–4, but not becoming widespread until after 1800.

The Tannehill Ironworks is the central feature of Tannehill Ironworks Historical State Park near the unincorporated town of McCalla in Tuscaloosa County, Alabama. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places as Tannehill Furnace, it was a major supplier of iron for Confederate ordnance. Remains of the old furnaces are located 12 miles (19 km) south of Bessemer off Interstate 59/Interstate 20 near the southern end of the Appalachian Mountains. The 2,063-acre (835 ha) park includes: the John Wesley Hall Grist Mill; the May Plantation Cotton Gin House; and the Iron & Steel Museum of Alabama.

Seend Ironstone Quarry and Road Cutting is a 3 acres (1.2 ha) Geological Site of Special Scientific Interest at Seend in Wiltshire, England, notified in 1965. The site contains facies of Lower Greensand containing specimens of fauna not found elsewhere.

Ferrous metallurgy is the metallurgy of iron and its alloys. The earliest surviving prehistoric iron artifacts, from the 4th millennium BC in Egypt, were made from meteoritic iron-nickel. It is not known when or where the smelting of iron from ores began, but by the end of the 2nd millennium BC iron was being produced from iron ores in the region from Greece to India,. The use of wrought iron was known by the 1st millennium BC, and its spread defined the Iron Age. During the medieval period, smiths in Europe found a way of producing wrought iron from cast iron, in this context known as pig iron, using finery forges. All these processes required charcoal as fuel.

Cornwall Iron Furnace is a designated National Historic Landmark that is administered by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission in Cornwall, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania in the United States. The furnace was a leading Pennsylvania iron producer from 1742 until it was shut down in 1883. The furnaces, support buildings and surrounding community have been preserved as a historical site and museum, providing a glimpse into Lebanon County's industrial past. The site is the only intact charcoal-burning iron blast furnace in its original plantation in the western hemisphere. Established by Peter Grubb in 1742, Cornwall Furnace was operated during the Revolution by his sons Curtis and Peter Jr. who were major arms providers to George Washington. Robert Coleman acquired Cornwall Furnace after the Revolution and became Pennsylvania's first millionaire. Ownership of the furnace and its surroundings was transferred to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in 1932.

Tilgate Park is a large recreational park situated south of Tilgate, South-East Crawley.

William Levett was an English clergyman. An Oxford-educated country rector, he was a pivotal figure in the use of the blast furnace to manufacture iron. With the patronage of the English Crown, furnaces in Sussex under Levett's ownership cast the first iron muzzle-loader cannons in England in 1543, a development which enabled England to ultimately reconfigure the global balance-of-power by becoming an ascendant naval force. William Levett continued to perform his ministerial duties while building an early munitions empire, and left the riches he accumulated to a wide variety of charities at his death.

St Leonard's Forest is at the western end of the Wealden Forest Ridge which runs from Horsham to Tonbridge, and is part of the High Weald Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. It lies on the ridge to the south of the A264 between Horsham and Crawley with the villages of Colgate and Lower Beeding within it. The A24 lies to west and A23 to the East and A272 through Cowfold to the south. Much has been cleared, but a large area is still wooded. Forestry England has 289 ha. which is open to the public, as are Owlbeech and Leechpool Woods to the east of Horsham, and Buchan Country Park to the SW of Crawley. The rest is private with just a few public footpaths and bridleways. Leonardslee Gardens were open to the public until July 2010 and re-opened in April 2019. An area of 85.4 hectares is St Leonards Forest Site of Special Scientific Interest.

The Lancashire hearth was used to fine pig iron, removing carbon to produce wrought iron.

Ashdown Forest formed an important part of the Wealden iron industry that operated from pre-Roman times until the early 18th century. The industry reached its peak in the two periods when the Weald was the main iron-producing region of Britain, namely in the first 200 years of the Roman occupation and during Tudor and early Stuart times. Iron-smelting in the former period was based on bloomery technology, while the latter depended for its rapid growth on the blast furnace, when the Ashdown area became the first in England to use this technology.