| Successor | Arkansas chapter of White Citizen's Council |

|---|---|

| Formation | February 1955 Pine Bluff, Arkansas, U.S. |

| Dissolved | March 1956 |

| Type | Hate group/Pro-segregation |

| Purpose | Maintaining segregation and white supremacy in the state of Arkansas. |

| Headquarters | Pine Bluff, Arkansas, U.S. |

President | L.D. Poynter |

Executive Secretary | Amis Gutheridge |

Spokesperson | Amis Gutheridge |

| Affiliations | White Citizen's Council |

White America, Inc., was an organization founded in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, in February 1955. The organization was created following the desegregation of schools in Arkansas, to attempt to prevent "any attempts by Negroes to enter white schools" in the state. [1] The group joined two other militant white supremacist organizations in September 1955 to attempt to intimidate the local school board of Hoxie to reverse its decision to integrate its schools.

The group's intimidating actions were so severe that a federal judge said they amounted to terrorism and placed an injunction on the organization and its affiliates to prevent them from contacting or otherwise interfering with the school board. This was the first time in U.S. history that a federal court had placed such an injunction on white supremacist intimidation. The group was affiliated with the White Citizens' Councils that existed throughout the United States during the Civil Rights Movement, as well as other state and regional segregationist organizations.

A year after its formation, White America, Inc., merged with the official White Citizens' Council chapter in Little Rock.

While the Civil Rights Movement was ongoing, several anti-integration groups founded to attempt to stop the racial desegregation and removals of discrimination which were beginning to occur. [2] [3] One such network of organizations was the White Citizens' Councils, which founded in 1954, [4] after the landmark U.S. Supreme Court ruling Brown v. Board of Education , that same year, that stated state laws permitting white and black segregation were found to be unconstitutional. [5] While the decision effectively overturned the Plessy v. Ferguson decision of 1896, which allowed states to segregate schools stating "separate educational facilities are inherently unequal", there was no true enforcement of this ruling in the south for many years. [6] Blatant discrimination continued to take place for decades via Jim Crow laws, which had mandated racial segregation in all public facilities in the states of the former Confederate States of America, and continued to be enforced in many ways until 1965. [7]

White America, Inc., was founded by three white supremacist employees of the Cotton Belt Railroad in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, in February 1955. [8] [9] [10] They formed the organization to, in the words of one of the co-founders, "perpetuate the white race and to endeavor to have this and future generations free of contamination of Negro blood". [11] The organization's main goal was to prevent or stop racial integration in the state's schools. [9] The president of the group stated they were going to stop "any attempts by Negroes to enter white schools" and that they would do so "on a peaceable basis_through legal action", but warned if that failed that "the people" would "take matters into their own hands". [12] The organization believed that the Brown vs. Board of Education ruling by the United States Supreme Court violated states' rights. [9] The co-founder and organization president, L. D. Poynter, stated at a meeting in Pine Bluff that if integration happened "in a few years we won't be able to identify ourselves as white or black". [11] The articles of incorporation of White America, Inc., entitled the executive office of the organization to the "Pine Bluff Labor Temple". [9]

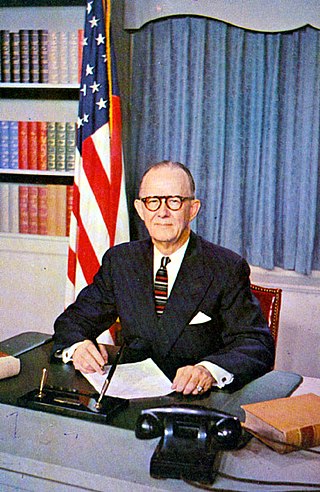

In February 1955 the group circulated a petition to request the state to place a referendum on the ballot to force the state government to "prevent integration". [9] The petition garnered over 6,000 signatures and was submitted to state senator Lawrence Blackwell. [10] In February 1956, a primary gubernatorial candidate (eventually elected as the 38th Governor of Arkansas), Orval Faubus, stated he held no objections to state employees signing the petition to have a pro-segregation measure placed on the ballot that November. [13] The following month White America, Inc., commended Faubus for his statement; according to Amis Guthridge, the group's executive secretary, Faubus had "finally declared himself for the principles which White America stands for", but stopped short of endorsing him for the 1956 Arkansas gubernatorial election. [14]

The organization worked with other white supremacist and anti-integration groups in the state, including the Hoxie Committee for Segregation and the White Citizen's Council of Arkansas. [15]

As in most areas in the Jim Crow south, Hoxie, Arkansas, had a segregated school system. This remained in place until June 11, 1955, after the Brown v. Board of Education ruling, the local school superintendent requested and received the unanimous support of the school board to integrate the entirety of the school system, including restrooms and cafeterias. [16]

When local segregationists heard of the decision they converged in the summer of 1955 to attempt to intimidate the superintendent and school board to reverse the decision. [8] [17] [18] [19] They called for the removal of the local school board, and even threatened the life of the superintendent. [19] To further intimidate the local community the groups began performing drive-by shootings of homes where black schoolchildren lived. [19] Guthridge stated that school integration was a "plan that was founded in Moscow in 1924 to mongrelize the white race in America" and claimed that white Methodist women "want integration so that the Negro can get in the white bedroom". [20] [21]

In Hoxie School District No. 46 of Lawrence Co., Ark. v. Brewer , 137 F. Supp. 364, the first time the federal government had ever intervened in a case of white supremacist's intimidation, U.S. federal judge Albert L. Reeves ruled that the actions by the anti-integration groups amounted to acts of terrorism, and ordered them to stop interfering with the Hoxie school board. [22] [23] White America, Inc., immediately appealed the injunction to the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals, which upheld the ruling by the lower court. [24] The Eighth Circuit ruling stated that the segregationists' conduct "was deliberately aimed at preventing the school board from affording to all the children within the school district the equal protection of the laws". [24]

Assisted by the Hoxie Committee for Segregation, White America, Inc., began a campaign to enroll over 100,000 members statewide for $2 ($18.23 adjusted for inflation in 2018) a year. [25] Guthridge, stated they intended to enlist over two thousand people in Lawrence County alone, after the Hoxie school integration dispute. [25]

In late 1956, after the group's unsuccessful segregation attempts in Hoxie, White America, Inc., merged with the Arkansas chapter of the White Citizens' Council. [21] [26]

Hoxie is a city in Lawrence County, Arkansas, United States. It lies immediately south of Walnut Ridge. The population was 2,780 at the 2010 census.

Orval Eugene Faubus was an American politician who served as the 36th Governor of Arkansas from 1955 to 1967, as a member of the Democratic Party.

The Council of Conservative Citizens is an American white supremacist organization. Founded in 1985, it advocates white nationalism, and supports some paleoconservative causes. In the organization's statement of principles, it states that they "oppose all efforts to mix the races of mankind".

The Women's Emergency Committee to Open Our Schools (WEC) was an organization formed by a group of socially prominent white women in the city of Little Rock, Arkansas during the Little Rock Crisis in 1958. The organization advocated for the integration of the Little Rock public school system and was a major obstacle to Governor Orval Faubus's efforts to prevent racial integration. The women spoke out in favor of a special election to remove segregationists from the Little Rock school board.

The Citizens' Councils were an associated network of white supremacist, segregationist organizations in the United States, concentrated in the South and created as part of a white backlash against the US Supreme Court's landmark Brown v. Board of Education ruling. The first was formed on July 11, 1954. The name was changed to the Citizens' Councils of America in 1956. With about 60,000 members across the Southern United States, the groups were founded primarily to oppose racial integration of public schools: the logical conclusion of the Brown v. Board of Education ruling.

James Douglas Johnson, known as "Justice Jim" Johnson, was an Arkansas legislator and jurist known for outspoken support of racial segregation during the mid-20th century. He served as an associate justice of the Arkansas Supreme Court from 1959 to 1966, and in the Arkansas Senate from 1951 to 1957. Johnson unsuccessfully sought several elected positions, including Governor of Arkansas in 1956 and 1966, and the United States Senate in 1968. A segregationist, Johnson was frequently compared to George Wallace of Alabama. He joined the Republican Party in 1983.

Lawrence Brooks Hays was an American lawyer and politician who served eight terms as a Democratic member of the United States House of Representatives from the State of Arkansas from 1943 to 1959. He was also a president of the Southern Baptist Convention.

Ronald Norwood Davies was a United States district judge of the United States District Court for the District of North Dakota. He is best known for his role in the Little Rock Integration Crisis in the fall of 1957. Davies ordered the desegregation of the previously all-white Little Rock Central High.

Segregation academies are private schools in the Southern United States that were founded in the mid-20th century by white parents to avoid having their children attend desegregated public schools. They were founded between 1954, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that segregated public schools were unconstitutional, and 1976, when the court ruled similarly about private schools.

Harry Scott Ashmore was an American journalist who won a Pulitzer Prize for his editorials in 1957 on the school integration conflict in Little Rock, Arkansas.

The Little Rock Nine were a group of nine African American students enrolled in Little Rock Central High School in 1957. Their enrollment was followed by the Little Rock Crisis, in which the students were initially prevented from entering the racially segregated school by Orval Faubus, the Governor of Arkansas. They then attended after the intervention of President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

The Mansfield school desegregation incident is a 1956 event in the Civil Rights Movement in Mansfield, Texas, a suburb of the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex.

The Arkansas Negro Boys' Industrial School (1927-1968) was a juvenile correctional facility for black male youth in Arkansas. There were two locations in 1936, one in Jefferson County and one in Wrightsville 10 miles (16 km) southeast of Little Rock. A fire in 1959 at the children's dormitory killed twenty-one victims.

The Stanley Plan was a package of 13 statutes adopted in September 1956 by the U.S. state of Virginia. The statutes were designed to ensure racial segregation would continue in that state's public schools despite the unanimous ruling of the U.S. Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) that school segregation was unconstitutional. The legislative program was named for Governor Thomas B. Stanley, a Democrat, who proposed the program and successfully pushed for its enactment. The Stanley plan was a critical element in the policy of "massive resistance" to the Brown ruling advocated by U.S. Senator Harry F. Byrd Sr. The plan also included measures designed to curb the Virginia state chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which many Virginia segregationists believed was responsible for "stirring up" litigation to integrate the public schools.

Dollarway High School is a comprehensive public high school in northwest Pine Bluff, Arkansas that serves grades 9 through 12. It is one of three public high schools in Pine Bluff and is a part of the Pine Bluff School District effective July 1, 2021. Prior to that point it was the only high school managed by the Dollarway School District. Within the state, the school is often referred to as Pine Bluff Dollarway.

Hoxie School District is a public school district based in Hoxie, Arkansas, United States. The Hoxie School District encompasses 124.17 square miles (321.6 km2) of land including all or portions of Lawrence County communities including Hoxie, small portions of Walnut Ridge, Sedgwick, and Minturn.

School integration in the United States is the process of ending race-based segregation within American public and private schools. Racial segregation in schools existed throughout most of American history and remains an issue in contemporary education. During the Civil Rights Movement school integration became a priority, but since then de facto segregation has again become prevalent.

This is a timeline of the civil rights movement in the United States, a nonviolent mid-20th century freedom movement to gain legal equality and the enforcement of constitutional rights for people of color. The goals of the movement included securing equal protection under the law, ending legally institutionalized racial discrimination, and gaining equal access to public facilities, education reform, fair housing, and the ability to vote.

Roy Vincent Harris was an American politician and newspaper publisher in the U.S. state of Georgia during the mid-1900s. From the 1920s until the 1940s, Harris served several terms in both the Georgia House of Representatives and the Georgia State Senate, and he served as the speaker of the house from 1937 to 1940 and again from 1943 to 1946. Historian Harold Paulk Henderson has called Harris "one of Georgia's most capable behind-the-scenes politicians".

The Ministers' Manifesto refers to a series of manifestos written and endorsed by religious leaders in Atlanta, Georgia, United States, during the 1950s. The first manifesto was published in 1957 and was followed by another the following year. The manifestos were published during the civil rights movement amidst a national process of school integration that had begun several years earlier. Many white conservative politicians in the Southern United States embraced a policy of massive resistance to maintain school segregation. However, the 80 clergy members that signed the manifesto, which was published in Atlanta's newspapers on November 3, 1957, offered several key tenets that they said should guide any debate on school integration, including a commitment to keeping public schools open, communication between both white and African American leaders, and obedience to the law. In October 1958, following the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation Temple bombing in Atlanta, 311 clergy members signed another manifesto that reiterated the points made in the previous manifesto and called on the governor of Georgia to create a citizens' commission to help with the eventual school integration process in Atlanta. In August 1961, the city initiated the integration of its public schools.