| Wichita Massacre | |

|---|---|

| Location | Wichita, Kansas, U.S. |

| Date | December 8–15, 2000 |

Attack type | Spree killing, robbery, rape, kidnapping, mass murder |

| Weapons | Lorcin L-380 pistols |

| Deaths | 5 (includes 1 death resulting from injuries sustained post-attack) |

| Injured | 2 |

| Perpetrators | Jonathan Carr Reginald Carr |

The Wichita Massacre, also known as the Wichita Horror, was a week-long violent crime spree perpetrated by brothers Reginald and Jonathan Carr in the city of Wichita, Kansas, between December 8 and 15, 2000. Five people were killed, and two people, a man and a woman, were severely wounded. The brothers were arrested and convicted of multiple counts of murder, kidnapping, robbery, and rape. They were both sentenced to death in October 2002. [1] Their vicious crimes created panic in the Wichita area resulting in an increase in the sales of guns, locks, and home security systems. [2]

The case has received significant attention because the killers' death sentences have been subject to various rulings related to the use of executions in Kansas. In 2004, the Kansas Supreme Court overturned the state's death penalty law, but the Kansas Attorney General appealed to the US Supreme Court, which upheld the constitutionality of the death penalty in Kansas. On July 25, 2014, the Kansas Supreme Court again overturned the Carrs' death sentences on a legal technicality relating to their original trial judge not giving each brother a separate penalty proceeding. [3] After an appeal by the state's attorney general to the US Supreme Court, it overturned the decision of the Kansas Supreme Court in January 2016 and reinstated the death sentences. [4] The Carr brothers are incarcerated on death row at El Dorado Correctional Facility.

The Carr brothers were from Dodge City, Kansas. Reginald Dexter Carr, Jr., was born on November 14, 1977. Jonathan Daniel Carr was born on March 30, 1980. At the time of the Wichita Massacre, both 23-year-old Reginald and 20-year-old Jonathan had lengthy criminal records.

On December 8, 2000, having recently arrived in Wichita, the brothers robbed and wounded 23-year-old Andrew Schreiber, an assistant baseball coach. Three days later, on December 11, they shot 55-year-old cellist and librarian Ann Walenta as she tried to escape from them in her car. She died three weeks later in hospital from her wounds.

On December 14, the brothers broke into a house at 12727 East Birchwood Drive in Wichita. Inside the property, which they had chosen at random, were Brad Heyka, Heather Muller, Aaron Sander, Jason Befort, and his girlfriend, a young woman identified as "Holly G." Heyka was a director of finance with a local financial services company; Muller was a local preschool teacher; Sander a former financial analyst who had been studying to become a priest; Befort was a local high school teacher; and Holly G. was a teacher. [5]

First, the Carrs searched the house for valuables. Befort had intended to propose to Holly, and she found this out when the Carrs discovered an engagement ring hidden in a popcorn box. After burgling the house, the Carrs forced their victims to strip naked and bound them. The brothers then repeatedly raped the two women and forced the men to engage in sexual acts with the women and the women with each other. After taking the victims in Befort's truck to ATMs to empty their bank accounts, they drove them to the closed Stryker Soccer Complex on the outskirts of Wichita, where they shot all five execution-style in the back of their heads. The Carrs then drove Befort's truck over their bodies and left them for dead. Holly G. survived because her plastic barrette deflected the bullet to the side of her head, while the other four were killed instantly. She walked naked for more than a mile in freezing weather to seek first aid and shelter at a house. Before getting medical treatment, she reported the incident and descriptions of her attackers to the couple who took her in before the police arrived.

After the killings, the Carrs returned to the house to ransack it for more valuables; while there, they used a golf club to beat Holly's pet dog, Nikki, to death. [6]

Police captured the Carr brothers the next day. Both Schreiber and the dying Walenta identified Reginald. The District Attorney said that they believed the motive was robbery. With the help of Holly's testimony at the trial, the brothers were convicted on nearly all 113 counts against them, including kidnapping, robbery, rape, four counts of capital murder, and one count of first-degree murder. Reginald Carr was convicted on 50 counts and Jonathan Carr on 43. They were sentenced to death for the capital murders, plus life in prison, with a minimum of decades before being eligible for parole. [3] Their cases were later appealed.

There has been continuing attention for the Carr brothers' case because of various rulings about the Kansas death penalty law and decisions by its high court on such cases. In 2004, the Kansas Supreme Court overturned the state's death penalty law, but the state attorney general appealed this ruling to the U.S. Supreme Court. It upheld the constitutionality of the state's death penalty law, which returned the Carrs and other condemned killers to death row.

On July 25, 2014, the Kansas Supreme Court announced it had overturned the Carr death sentences on appeal. The six justice-majority said they did so because the trial judge failed to adequately separate the penalty proceedings for each defendant. According to a release from the Kansas Supreme Court public information officer, the court unanimously reversed three of each defendant's four capital convictions because jury instructions on sex-crime-based capital murder were "fatally erroneous and three of the multiple-homicide capital murder charges duplicated the first." [3]

The high court upheld most of the convictions against each of the brothers despite other purported lower-court errors. The court ruled that the brothers were entitled to separate sentencing trials, as "differentiation in the moral culpability of two defendants" can cause a jury "to show mercy to one while refusing to show mercy to the other." [3] Even if the death penalties were not upheld, each of the Carrs was already sentenced to serve at least "70 to 80 years" in prison before being eligible for parole. [4]

The Kansas Attorney General appealed the high court's ruling to the US Supreme Court, which in March 2015 agreed to hear the Carr brothers' sentencing case, together with another death-penalty case from the state. In January 2016, the United States Supreme Court (in an 8–1 ruling) reinstated the death sentences, overturning the Kansas Supreme Court, deciding that neither the jury instructions that were challenged by the Carrs' legal counsel, nor the combined sentencing proceedings, violated the Constitution. [4] [7] The Kansas Supreme Court affirmed the death penalty for the brothers on January 21, 2022. [8]

The victims were white and the Carr brothers are black, but the District Attorney held that there was no prima facie evidence of a racial crime. Based on the robberies, Sedgwick County District Attorney Nola Foulston decided against treating these incidents as hate crimes. Conservative media commentators David Horowitz, Michelle Malkin, and Thomas Sowell said the crimes were downplayed; they felt the national media suppressed the stories due to political correctness. [9] [ better source needed ] Sowell, an African-American conservative, has said the media has a double standard regarding interracial offenses, tending to play up "vicious crimes by whites against blacks" but play down "equally vicious crimes by blacks against whites". [2]

Years later, The Wichita Eagle commented that the deaths of four young black people who were murdered by a young black man eight days before the "Wichita Massacre" in 2000 received less general media coverage than the murders committed by the Carr brothers. In this case, Cornelius Oliver, 19, killed his girlfriend, Raeshawnda Wheaton, 18, at her house, as well as her roommate Dessa Ford, and friends Jermaine Levy and Quincy Williams, who were visiting the women. Oliver shot the men in the back of the head where they sat on a couch. The couple had been known to have a "volatile, violent relationship". The police arrested Oliver that day; he still had blood on his shoes. [10]

Some members of the black community questioned why the murders of the four young black people was superseded by attention given to the Carr brothers' killing of four young white people. A relative of Wheaton asked, "How could one be any worse than the other, if the results [multiple deaths] were the same?" [10] The deaths of Wheaton and her friends were characterized by Oliver having had a personal relationship with at least one of his victims, unlike the Carrs who chose their victims at random. In addition, the Carrs committed rapes, as well as other assaults and abuses, to the victims. There was no prolonged torture or sexual component in the Wheaton case. Oliver was convicted of the four murders and is serving a life sentence in prison, with no possibility of parole before 2140. [10]

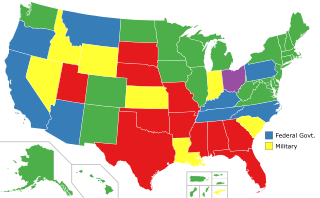

In the United States, capital punishment is a legal penalty throughout the country at the federal level, in 27 states, and in American Samoa. It is also a legal penalty for some military offenses. Capital punishment has been abolished in 23 states and in the federal capital, Washington, D.C. It is usually applied for only the most serious crimes, such as aggravated murder. Although it is a legal penalty in 27 states, 20 states currently have the ability to execute death sentences, with the other seven, as well as the federal government, being subject to different types of moratoriums.

In the U.S. state of California, capital punishment is not allowed to be carried out as of March 2019, because executions were halted by an official moratorium ordered by Governor Gavin Newsom. Before the moratorium, executions had been frozen by a federal court order since 2006, and the litigation resulting in the court order has been on hold since the promulgation of the moratorium. Thus, there will be a court-ordered moratorium on executions after the termination of Newsom's moratorium if capital punishment remains a legal penalty in California by then.

The U.S. state of Washington enforced capital punishment until the state's capital punishment statute was declared null and void and abolished in practice by a state Supreme Court ruling on October 11, 2018. The court ruled that it was unconstitutional as applied due to racial bias however it did not render the wider institution of capital punishment unconstitutional and rather required the statute to be amended to eliminate racial biases. From 1904 to 2010, 78 people were executed by the state; the last was Cal Coburn Brown on September 10, 2010. In April 2023, Governor Jay Inslee signed SB5087 which formally abolished capital punishment in Washington State and removed provisions for capital punishment from state law.

Capital punishment is one of two possible penalties for aggravated murder in the U.S. state of Oregon, with it being required by the Constitution of Oregon.

A home invasion, also called a hot prowl burglary, is a sub-type of burglary in which an offender unlawfully enters into a building residence while the occupants are inside. The overarching intent of a hot prowl burglary can be theft, robbery, assault, sexual assault, murder, kidnapping, or another crime, either by stealth or direct force. Hot prowl burglaries are considered especially dangerous by law enforcement because of the potential for a violent confrontation between the occupant and the offender.

Roper v. Simmons, 543 U.S. 551 (2005), is a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of the United States in which the Court held that it is unconstitutional to impose capital punishment for crimes committed while under the age of 18. The 5–4 decision overruled Stanford v. Kentucky, in which the court had upheld execution of offenders at or above age 16, and overturned statutes in 25 states.

The rapes and murders of Julie and Robin Kerry occurred on April 5, 1991, on the Chain of Rocks Bridge over the Mississippi River in St. Louis, Missouri. The two sisters were raped and then murdered by a group of four males, who also attempted to murder the sisters' cousin.

Coker v. Georgia, 433 U.S. 584 (1977), held that the death penalty for rape of an adult woman was grossly disproportionate and excessive punishment, and therefore unconstitutional under the Eighth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. A few states continued to have child rape statutes that authorized the death penalty. In Kennedy v. Louisiana (2008), the court expanded Coker, ruling that the death penalty is unconstitutional in all cases that do not involve intentional homicide or crimes against the State.

Wrongful execution is a miscarriage of justice occurring when an innocent person is put to death by capital punishment. Cases of wrongful execution are cited as an argument by opponents of capital punishment, while proponents say that the argument of innocence concerns the credibility of the justice system as a whole and does not solely undermine the use of the death penalty.

Kansas v. Marsh, 548 U.S. 163 (2006), is a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held that a Kansas death penalty statute was consistent with the United States Constitution. The statute in question provided for a death sentence when the aggravating factors and mitigating factors were of equal weight.

Capital punishment in Connecticut formerly existed as an available sanction for a criminal defendant upon conviction for the commission of a capital offense. Since the 1976 United States Supreme Court decision in Gregg v. Georgia until Connecticut repealed capital punishment in 2012, Connecticut had only executed one person, Michael Bruce Ross in 2005. Initially, the 2012 law allowed executions to proceed for those still on death row and convicted under the previous law, but on August 13, 2015, the Connecticut Supreme Court ruled that applying the death penalty only for past cases was unconstitutional.

Bigby v. Dretke 402 F.3d 551, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit heard a case appealed from the United States District Court for the Northern District of Texas on the issue of the instructions given to a jury in death penalty sentencing. The decision took into account the recent United States Supreme Court decisions concerning the relevance of mitigating evidence in sentencing, as in Penry v. Lynaugh.

Kennedy v. Louisiana, 554 U.S. 407 (2008), is a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of the United States which held that the Eighth Amendment's Cruel and Unusual Punishments Clause prohibits the imposition of the death penalty for a crime in which the victim did not die or the victim's death was not intended.

The Double Jeopardy Clause of the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution provides: "[N]or shall any person be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb..." The four essential protections included are prohibitions against, for the same offense:

Scott Allen Hain was the last person executed in the United States for crimes committed as a juvenile. Hain was executed by Oklahoma for a double murder–kidnapping he committed when he was 17 years old.

Paul George Cassell is a former United States district judge of the United States District Court for the District of Utah, who is currently the Ronald N. Boyce Presidential Professor of Criminal Law and University Distinguished Professor of Law at the S.J. Quinney College of Law at the University of Utah. He is best known as an expert in, and proponent of, victims' rights.

Capital punishment is currently a legal penalty in the U.S. state of Kansas, although it has not been used since 1965.

Kansas v. Carr, 577 U.S. 108 (2016), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States clarified several procedures for sentencing defendants in capital cases. Specifically, the Court held that judges are not required to affirmatively instruct juries about the burden of proof for establishing mitigating evidence, and that joint trials of capital defendants "are often preferable when the joined defendants’ criminal conduct arises out of a single chain of events". This case included the last majority opinion written by Justice Antonin Scalia before his death in February 2016.

Kho Jabing, later in life Muhammad Kho Abdullah, was a Malaysian of mixed Chinese and Iban descent from Sarawak, Malaysia, who partnered with a friend to rob and murder a Chinese construction worker named Cao Ruyin in Singapore on 17 February 2008. While his accomplice was eventually jailed and caned for robbery, Kho Jabing was convicted of murder and sentenced to death on 30 July 2010, and lost his appeal on 24 May 2011.

Capital punishment in Malawi is a legal punishment for certain crimes. The country abolished the death penalty following a Malawian Supreme Court ruling in 2021, but it was soon reinstated. However, the country is currently under a death penalty moratorium, which has been in place since the latest execution in 1992.