Related Research Articles

A witch-hunt, or a witch purge, is a search for people who have been labeled witches or a search for evidence of witchcraft. Practicing evil spells or incantations was proscribed and punishable in early human civilizations in the Middle East. In medieval Europe, witch-hunts often arose in connection to charges of heresy from Christianity. An intensive period of witch-hunts occurring in Early Modern Europe and to a smaller extent Colonial America, took place about 1450 to 1750, spanning the upheavals of the Counter Reformation and the Thirty Years' War, resulting in an estimated 35,000 to 50,000 executions. The last executions of people convicted as witches in Europe took place in the 18th century. In other regions, like Africa and Asia, contemporary witch-hunts have been reported from sub-Saharan Africa and Papua New Guinea, and official legislation against witchcraft is still found in Saudi Arabia and Cameroon today.

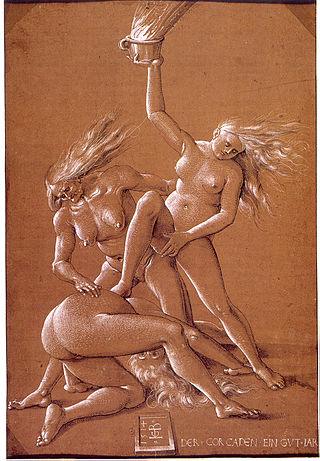

European witchcraft is a multifaceted historical and cultural phenomenon that unfolded over centuries, leaving a mark on the continent's social, religious, and legal landscapes. The roots of European witchcraft trace back to classical antiquity when concepts of magic and religion were closely related, and society closely integrated magic and supernatural beliefs. Ancient Rome, then a pagan society, had laws against harmful magic. In the Middle Ages, accusations of heresy and devil worship grew more prevalent. By the early modern period, major witch hunts began to take place, partly fueled by religious tensions, societal anxieties, and economic upheaval. Witches were often viewed as dangerous sorceresses or sorcerers in a pact with the Devil, capable of causing harm through black magic. A feminist interpretation of the witch trials is that misogynist views of women led to the association of women and malevolent witchcraft.

Werewolf witch trials were witch trials combined with werewolf trials. Belief in werewolves developed parallel to the belief in European witches, in the course of the Late Middle Ages and the Early Modern period. Like the witchcraft trials as a whole, the trial of supposed werewolves emerged in what is now Switzerland during the Valais witch trials in the early 15th century and spread throughout Europe in the 16th, peaking in the 17th and subsiding by the 18th century. The persecution of werewolves and the associated folklore is an integral part of the "witch-hunt" phenomenon, albeit a marginal one, accusations of lycanthropy involved in only a small fraction of witchcraft trials.

In the early modern period, from about 1400 to 1775, about 100,000 people were prosecuted for witchcraft in Europe and British America. Between 40,000 and 60,000 were executed. The witch-hunts were particularly severe in parts of the Holy Roman Empire. Prosecutions for witchcraft reached a high point from 1560 to 1630, during the Counter-Reformation and the European wars of religion. Among the lower classes, accusations of witchcraft were usually made by neighbors, and women made formal accusations as much as men did. Magical healers or 'cunning folk' were sometimes prosecuted for witchcraft, but seem to have made up a minority of the accused. Roughly 80% of those convicted were women, most of them over the age of 40. In some regions, convicted witches were burnt at the stake.

Barbara Zdunk was an ethnically Polish alleged arsonist accused of witchcraft. Zdunk lived in the town of Rößel, in what was then East Prussia, and is now Reszel in Poland. She is considered by many to have been the last woman executed for witchcraft in Europe. Although, the accusations of witchcraft were listed in her case, witchcraft was not a criminal offense in Prussia at the time.

The Doruchów witch trial was a witch trial which took place in the village of Doruchów in Poland in the 18th century. It was the last mass trial of sorcery and witchcraft in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Krystyna Ceynowa, also spelled as Cejnowa, was an ethnic Polish victim of murder by lynching and an alleged witch. Accused of sorcery, she was subjected to the ordeal of water and drowned in Ceynowa. She was the last person in Poland and among the last people in Europe to be subjected to lynching on the grounds of sorcery and witchcraft.

In early modern Scotland, in between the early 16th century and the mid-18th century, judicial proceedings concerned with the crimes of witchcraft took place as part of a series of witch trials in Early Modern Europe. In the late middle age there were a handful of prosecutions for harm done through witchcraft, but the passing of the Witchcraft Act 1563 made witchcraft, or consulting with witches, capital crimes. The first major issue of trials under the new act were the North Berwick witch trials, beginning in 1590, in which King James VI played a major part as "victim" and investigator. He became interested in witchcraft and published a defence of witch-hunting in the Daemonologie in 1597, but he appears to have become increasingly sceptical and eventually took steps to limit prosecutions.

Witchcraft in Orkney possibly has its roots in the settlement of Norsemen on the archipelago from the eighth century onwards. Until the early modern period magical powers were accepted as part of the general lifestyle, but witch-hunts began on the mainland of Scotland in about 1550, and the Scottish Witchcraft Act of 1563 made witchcraft or consultation with witches a crime punishable by death. One of the first Orcadians tried and executed for witchcraft was Allison Balfour, in 1594. Balfour, her elderly husband and two young children, were subjected to severe torture for two days to elicit a confession from her.

Sweden was a country with few witch trials compared to other countries in Europe. In Sweden, about four hundred people were executed for witchcraft prior to the last case in 1704. Most of these cases occurred during a short but intense period; the eight years between 1668 and 1676, when the witch hysteria called Det stora oväsendet took place, causing a large number of witch trials in the country. It is this infamous period of intensive witch hunt that is most well known and explored.

In the Holy Roman Empire, witch trials composed of the areas of the present day Germany, were the most extensive in Europe and in the world, both to the extent of the witch trials as such as well as to the number of executions.

The Witch trials in Spain were few in comparison with most of Europe. The Spanish Inquisition preferred to focus on the crime of heresy and, consequently, did not consider the persecution of witchcraft a priority and in fact discouraged it rather than have it conducted by the secular courts. This was similar to the Witch trials in Portugal and, with a few exceptions, mainly successful. However, while the Inquisition discouraged witch trials in Spain proper, it did encourage the particularly severe Witch trials in the Spanish Netherlands.

The Witch trials in Portugal were perhaps the fewest in all of Europe. Similar to the Spanish Inquisition in neighboring Spain, the Portuguese Inquisition preferred to focus on the persecution of heresy and did not consider witchcraft to be a priority. In contrast to the Spanish Inquisition, however, the Portuguese Inquisition was much more efficient in preventing secular courts from conducting witch trials, and therefore almost managed to keep Portugal free from witch trials. Only seven people are known to have been executed for sorcery in Portugal.

The Witch trials in Denmark are poorly documented, with the exception of the region of Jylland in the 1609–1687 period. The most intense period in the Danish witchcraft persecutions was the great witch hunt of 1617–1625, when most executions took place, which was affected by a new witchcraft act introduced in 1617.

The witch trials in Norway were the most intense among the Nordic countries. There seems to be around an estimated 277 to 350 executions between 1561 and 1760. Norway was in a union with Denmark during this period, and the witch trials were conducted by instructions from Copenhagen. The authorities and the clergy conducted the trials using demonology handbooks and used interrogation techniques and sometimes torture. After a guilty verdict, the condemned was forced to expose accomplices and commonly deaths occurred due to torture or prison. Witch trials were in decline by the 1670s as judicial and investigative methods were improved. A Norwegian law from 1687 maintained the death penalty for witchcraft, and the last person to be sentenced guilty of witchcraft in Norway was Birgitte Haldorsdatter in 1715. The Witchcraft Act was formally in place until 1842.

Witch trials in Latvia and Estonia were mainly conducted by the Baltic German elite of clergy, nobility and burghers against the indigenous peasantry in order to persecute Paganism by use of Christian demonology and witchcraft ideology. In this aspect, they are similar to the Witch trials in Iceland. They are badly documented, as many would have been conducted by the private estate courts of the landlords, which did not preserve any court protocols.

The witch trials in the Netherlands were among the smallest in Europe. The Netherlands are known for having discontinued their witchcraft executions earlier than any other European country. The provinces began to phase out capital punishment for witchcraft beginning in 1593. The last trial in the Northern Netherlands took place in 1610.

The Witch trials in Finland were conducted in connection to Sweden and were relatively few with the exception of the 1660s and 1670s, when a big witch hunt affected both Finland and Sweden. Finland differed from most of Europe in that an uncommonly large part of the accused were men, which it had in common with the witch trials in Iceland. Most of the people accused in Finland were men, so called "wise men" hired to perform magic by people. From 1674 to 1678, a real witch hysteria broke out in Ostrobothnia, during which twenty women and two men were executed.

The Witch trials in Hungary were conducted over a longer period of time than in most countries in Europe, as documented witch trials are noted as early as the Middle Ages and lasted until the late 18th-century. During the 16th and 17th centuries Hungary was divided into three parts: Habsburg Hungary, Ottoman Hungary and Transylvania, with some differences between them in regard to the witch hunt. The most intense period of witch hunt in Hungary took place in the 18th-century, at a time when they were rare in the rest of Europe except Poland. The trials finally stopped in 1768 by abolition of the death penalty for witchcraft by Austria, which controlled Hungary at the time. An illegal witch trial and execution took place in 1777.

The witch trials in Orthodox Russia were different in character than the witch trials in Roman Catholic and Protestant Europe due to the differing cultural and religious background. It is often treated as an exception to modern theories of witch-hunts, due to the perceived difference in scale, the gender distribution of those accused, and the lack of focus on the demonology of a witch who made a pact with Satan and attended a Witches' Sabbath, but only on the practice of magic as such.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 (in German) Jacek Wijaczka (5 February 2008), Hexenprozesse in Polen vom 16. bis zum 18. Jahrhundert Archived 2017-02-11 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Jóźwiak, Krzysztof (15 October 2016). "Procesy czarownic w Rzeczypospolitej Obojga Narodów". www.rp.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2020-09-01.

- 1 2 Jabłońska, Ewa (16 September 2019). "Polskie polowanie na czarownice. Jak do tego doszło?". www.national-geographic.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2020-09-01.

- ↑ Haelschner, Hugo (1868). System des Preußischen Strafrechts[System of Prussian criminal law] (in German). Bonn: Adolph Marcus.

- 1 2 Tazbir, Janusz (15 September 2001). "Liczenie wiedźm". www.polityka.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2020-09-01.