Related Research Articles

Witchcraft, as most commonly understood in both historical and present-day communities, is the use of alleged supernatural powers of magic. A witch is a practitioner of witchcraft. Traditionally, "witchcraft" means the use of magic or supernatural powers to inflict harm or misfortune on others, and this remains the most common and widespread meaning. According to Encyclopedia Britannica, "Witchcraft thus defined exists more in the imagination of contemporaries than in any objective reality. Yet this stereotype has a long history and has constituted for many cultures a viable explanation of evil in the world". The belief in witchcraft has been found in a great number of societies worldwide. Anthropologists have applied the English term "witchcraft" to similar beliefs in occult practices in many different cultures, and societies that have adopted the English language have often internalised the term.

A witch-hunt, or a witch purge, is a search for people who have been labeled witches or a search for evidence of witchcraft. Practicing evil spells or incantations was proscribed and punishable in early human civilizations in the Middle East. In medieval Europe, witch-hunts often arose in connection to charges of heresy from Christianity. An intensive period of witch-hunts occurring in Early Modern Europe and to a smaller extent Colonial America, took place about 1450 to 1750, spanning the upheavals of the Counter Reformation and the Thirty Years' War, resulting in an estimated 35,000 to 50,000 executions. The last executions of people convicted as witches in Europe took place in the 18th century. In other regions, like Africa and Asia, contemporary witch-hunts have been reported from sub-Saharan Africa and Papua New Guinea, and official legislation against witchcraft is still found in Saudi Arabia and Cameroon today.

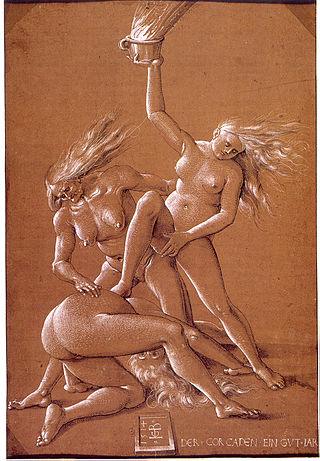

A Witches' Sabbath is a purported gathering of those believed to practice witchcraft and other rituals. The phrase became especially popular in the 20th century.

European witchcraft is a multifaceted historical and cultural phenomenon that unfolded over centuries, leaving a mark on the continent's social, religious, and legal landscapes. The roots of European witchcraft trace back to classical antiquity when concepts of magic and religion were closely related, and society closely integrated magic and supernatural beliefs. Ancient Rome, then a pagan society, had laws against harmful magic. In the Middle Ages, accusations of heresy and devil worship grew more prevalent. By the early modern period, major witch hunts began to take place, partly fueled by religious tensions, societal anxieties, and economic upheaval. Witches were often viewed as dangerous sorceresses or sorcerers in a pact with the Devil, capable of causing harm through black magic. A feminist interpretation of the witch trials is that misogynist views of women led to the association of women and malevolent witchcraft.

In the early modern period, from about 1400 to 1775, about 100,000 people were prosecuted for witchcraft in Europe and British America. Between 40,000 and 60,000 were executed. The witch-hunts were particularly severe in parts of the Holy Roman Empire. Prosecutions for witchcraft reached a high point from 1560 to 1630, during the Counter-Reformation and the European wars of religion. Among the lower classes, accusations of witchcraft were usually made by neighbors, and women made formal accusations as much as men did. Magical healers or 'cunning folk' were sometimes prosecuted for witchcraft, but seem to have made up a minority of the accused. Roughly 80% of those convicted were women, most of them over the age of 40. In some regions, convicted witches were burnt at the stake.

The trials of the Pendle witches in 1612 are among the most famous witch trials in English history, and some of the best recorded of the 17th century. The twelve accused lived in the area surrounding Pendle Hill in Lancashire, and were charged with the murders of ten people by the use of witchcraft. All but two were tried at Lancaster Assizes on 18–19 August 1612, along with the Samlesbury witches and others, in a series of trials that have become known as the Lancashire witch trials. One was tried at York Assizes on 27 July 1612, and another died in prison. Of the eleven who went to trial – nine women and two men – ten were found guilty and executed by hanging; one was found not guilty.

Helen Ukpabio is the founder and head of African Evangelical franchise Liberty Foundation Gospel Ministries based in Calabar, Cross River State, Nigeria. She is widely accused of causing large-scale harassment and violence against children accused of witchcraft.

The Samlesbury witches were three women from the Lancashire village of Samlesbury – Jane Southworth, Jennet Bierley, and Ellen Bierley – accused by a 14-year-old girl, Grace Sowerbutts, of practising witchcraft. Their trial at Lancaster Assizes in England on 19 August 1612 was one in a series of witch trials held there over two days, among the most infamous in English history. The trials were unusual for England at that time in two respects: Thomas Potts, the clerk to the court, published the proceedings in his The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches in the Countie of Lancaster; and the number of the accused found guilty and hanged was unusually high, ten at Lancaster and another at York. All three of the Samlesbury women were acquitted.

The Mora witch trial, which took place in Mora, Sweden, in 1669, is the most internationally famous Swedish witch trial. Reports of the trial spread throughout Europe, and a provocative German illustration of the execution is considered to have had some influence on the Salem witch trials. It was the first mass execution during the great Swedish witch hunt of 1668–1676.

Throughout the era of the European witch trials in the Early Modern period, from the 15th to the 18th century, there were protests against both the belief in witches and the trials. Even those protestors who believed in witchcraft were typically sceptical about its actual occurrence.

Witchcraft accusations against children in Africa have received increasing international attention in the first decade of the 21st century.

Europe's Inner Demons: An Enquiry Inspired by the Great Witch-Hunt is a historical study of the beliefs regarding European witchcraft in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe, with particular reference to the development of the witches' sabbat and its influence on the witch trials in the Early Modern period. It was written by the English historian Norman Cohn, then of the University of Sussex, and first published by Sussex University Press in association with Heinemann Educational Books in 1975. It was released as a part of a series of academic books entitled 'Studies in the Dynamics of Persecution and Extermination' that were funded by the Columbus Centre and edited by Cohn himself.

Leo Igwe is a Nigerian human rights advocate and humanist. Igwe is a former Western and Southern African representative of the International Humanist and Ethical Union, and has specialized in campaigning against and documenting the impacts of child witchcraft accusations. He holds a Ph.D. from the Bayreuth International School of African Studies at the University of Bayreuth in Germany, having earned a graduate degree in philosophy from the University of Calabar, in Nigeria. Igwe's human rights advocacy has brought him into conflict with high-profile witchcraft believers, such as Liberty Foundation Gospel Ministries, because of his criticism of what he describes as their role in the violence and child abandonment that sometimes result from accusations of witchcraft.

In early modern Scotland, in between the early 16th century and the mid-18th century, judicial proceedings concerned with the crimes of witchcraft took place as part of a series of witch trials in Early Modern Europe. In the late middle age there were a handful of prosecutions for harm done through witchcraft, but the passing of the Witchcraft Act 1563 made witchcraft, or consulting with witches, capital crimes. The first major issue of trials under the new act were the North Berwick witch trials, beginning in 1590, in which King James VI played a major part as "victim" and investigator. He became interested in witchcraft and published a defence of witch-hunting in the Daemonologie in 1597, but he appears to have become increasingly sceptical and eventually took steps to limit prosecutions.

The great Scottish witch hunt of 1649–50 was a series of witch trials in Scotland. It is one of five major hunts identified in early modern Scotland and it probably saw the most executions in a single year.

Witch-hunts are a contemporary phenomenon occurring globally, with notable occurrences in Sub-Saharan Africa, India, Nepal, and Papua New Guinea. Modern witch-hunts surpass the body counts of early-modern witch-hunting. Sub-Saharan Africa, particularly the Democratic Republic of Congo, South Africa, Tanzania, Kenya, and Nigeria, experiences a high prevalence of witch-hunting. In Cameroon, accusations have resurfaced in courts, often involving child-witchcraft scares. Gambia witnessed government-sponsored witch hunts, leading to abductions, forced confessions, and deaths.

The Bute witches were six Scottish women accused of witchcraft and interrogated in the parish of Rothesay on Bute during the Great Scottish Witch Hunt of 1661–62. The Privy Council granted a Commission of Justiciary for a local trial to be held and four of the women – believed by historians to be Margaret McLevin, Margaret McWilliam, Janet Morrison and Isobell McNicoll – were executed in 1662; a fifth may have died while incarcerated. One woman, Jonet NcNicoll, escaped from prison before she could be executed but when she returned to the island in 1673 the sentence was implemented.

The witch trials in Connecticut, also sometimes referred to as the Hartford witch trials, occurred from 1647 to 1663. They were the first large-scale witch trials in the American colonies, predating the Salem Witch Trials by nearly thirty years. John M. Taylor lists a total of 37 cases, 11 of which resulted in executions. The execution of Alse Young of Windsor in the spring of 1647 was the beginning of the witch panic in the area, which would not come to an end until 1670 with the release of Katherine Harrison.

During a 104-year period from 1626 to 1730, there are documented Virginia Witch Trials, hearings and prosecutions of people accused of witchcraft in Colonial Virginia. More than two dozen people are documented having been accused, including two men. Virginia was the first colony to have a formal accusation of witchcraft in 1626, and the first formal witch trial in 1641.

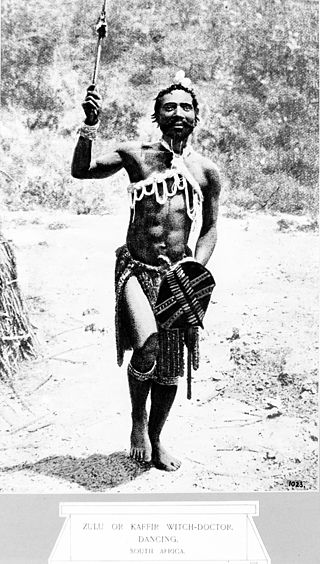

In Africa, witchcraft refers to various beliefs and practices. These beliefs often play a significant role in shaping social dynamics and can influence how communities address challenges and seek spiritual assistance. However much of what witchcraft represents in Africa has been susceptible to misunderstandings and confusion, thanks in no small part to a tendency among western scholars since the time of Margaret Murray to approach the subject through a comparative lens vis-a-vis European witchcraft. The definition of witchcraft differs between Africans and Europeans which causes misunderstandings of African conjure practices among Europeans. While some colonialists tried to eradicate witch hunting by introducing legislation to prohibit accusations of witchcraft, some of the countries where this was the case have formally recognized the existence of witchcraft via the law. This has produced an environment that encourages persecution of suspected witches.

References

- ↑ Secker, Emilie (2012-12-12). "Witchcraft stigmatization in Nigeria: Challenges and successes in the implementation of child rights". International Social Work. 56 (1): 22–36. doi:10.1177/0020872812459065. ISSN 0020-8728. S2CID 143707973.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Golden, Richard M. Encyclopedia of Witchcraft: The Western Tradition s.v. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2006.

- ↑ Poole, Robert (June 2012). "Witchcraft, history and children: interpreting England's biggest witch trial, 1612". Teaching History. 147: 36–37 – via JStor.

- ↑ Bailey, Michael D. Historical Dictionary of Witchcraft (Historical Dictionaries of Religions, Philosophies and Movements). Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2003.

- ↑ Cf. John Crewdson. By Silence Betrayed: Sexual Abuse of Children in America. (Boston: Little, Brown, 1988), 170.

- ↑ Burns, William E. Witch Hunts in Europe and America: An Encyclopedia. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2003.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Walinski-Kiehl, Robert S. (August 1996). "The devil's children: child witch-trials in early modern Germany". Continuity and Change. 11 (2): 171–189. doi:10.1017/S0268416000003301. ISSN 1469-218X. S2CID 145158797.

- 1 2 3 4 Roper, Lyndal (2000). "'Evil Imaginings and Fantasies': Child-Witches and the End of the Witch Craze". Past & Present. 167 (167): 107–139. doi:10.1093/past/167.1.107. ISSN 0031-2746. JSTOR 651255.

- ↑ Rowlands, Alison. The 'Little Witch Girl' of Rothenburg. History Review, 42(Mar 2002)27.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Willumsen, Liv Helene (2013-02-01). "Children accused of witchcraft in 17th-century Finnmark". Scandinavian Journal of History. 38 (1): 18–41. doi:10.1080/03468755.2012.741450. ISSN 0346-8755. S2CID 96469672.

- ↑ Ruickbie, Leo. Child Witches: From Imaginary Cannibalism to Ritual Abuse. Paranthropology, 3.3 (July 2012), pp. 13-21.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fontaine, Jean La (2009). The Devil's Children (1st ed.). Routledge. ISBN 9781315615479.

- 1 2 Laming, Lord (2001). The Victoria Climbie Inquiry. COI Communications. pp. 37–50.

- 1 2 Adinkrah, Mensah (2011-09-01). "Child witch hunts in contemporary Ghana". Child Abuse & Neglect. 35 (9): 741–752. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.05.011. ISSN 0145-2134. PMID 21943497.

- ↑ Joselow, Gabe (October 15, 2012). "Children Accused of Witchcraft Left Vulnerable in Central African Republic". Voice of American News / FIND– via ProQuest.

- ↑ CONGO RELATIVES ACCUSING KIDS OF WITCHCRAFT :[ALL Edition]. (2006, August 30). The Augusta Chronicle , p. A11. Retrieved December 1, 2008, from ProQuest NewsStand database. (Document ID: 1116345621).

- 1 2 Faith Karimi. "Abuse of child 'witches' on rise, aid group says". CNN.

- 1 2 3 4 Van Der Meer, Erwin (June 2013). "Child witchcraft accusations in Southern Malawi". Australasian Review of African Studies, the. 34 (1): 129.

- ↑ Children are targets of Nigerian witch hunt. (The Observer, 9 December 2007)

- ↑ STUDIA INSTITUTI ANTHROPOS, Vol. 41 Anthony J. Gittins : Mende Religion. Steyler Verlag, Nettetal, 1987. p. 200

- ↑ "Felix Riedel: Children in African Witch-Hunts – An introduction for Scientists and Social Workers". whrin.org.

- ↑ Riedel, Felix (2012). "Children in African Witch-Hunts - An Introduction for Scientists and Social Workers" (PDF).