The North Berwick witch trials were the trials in 1590 of a number of people from East Lothian, Scotland, accused of witchcraft in the St Andrew's Auld Kirk in North Berwick on Halloween night. They ran for two years, and implicated over 70 people. These included Francis Stewart, 5th Earl of Bothwell, on charges of high treason.

Agnes Sampson was a Scottish healer and purported witch. Also known as the "Wise Wife of Keith", Sampson was involved in the North Berwick witch trials in the later part of the sixteenth century.

Janet Horne was the last person to be executed legally for witchcraft in the British Isles.

In early modern Scotland, in between the early 16th century and the mid-18th century, judicial proceedings concerned with the crimes of witchcraft took place as part of a series of witch trials in Early Modern Europe. In the late middle age there were a handful of prosecutions for harm done through witchcraft, but the passing of the Witchcraft Act 1563 made witchcraft, or consulting with witches, capital crimes. The first major issue of trials under the new act were the North Berwick witch trials, beginning in 1590, in which King James VI played a major part as "victim" and investigator. He became interested in witchcraft and published a defence of witch-hunting in the Daemonologie in 1597, but he appears to have become increasingly sceptical and eventually took steps to limit prosecutions.

Geillis Duncan also spelled Gillis Duncan was a young maidservant in 16th century Scotland who was accused of being a witch. She was also the first recorded British named player of the mouth harp.

Margaret Bane also called Clerk, was a Scottish midwife and prominent victim of The Great Scottish Witch Hunt of 1597.

Witchcraft in Orkney possibly has its roots in the settlement of Norsemen on the archipelago from the eighth century onwards. Until the early modern period magical powers were accepted as part of the general lifestyle, but witch-hunts began on the mainland of Scotland in about 1550, and the Scottish Witchcraft Act of 1563 made witchcraft or consultation with witches a crime punishable by death. One of the first Orcadians tried and executed for witchcraft was Allison Balfour, in 1594. Balfour, her elderly husband and two young children, were subjected to severe torture for two days to elicit a confession from her.

The Pittenweem witches were five Scottish women accused of witchcraft in the small fishing village of Pittenweem in Fife on the east coast of Scotland in 1704. Another two women and a man were named as accomplices. Accusations made by a teenage boy, Patrick Morton, against a local woman, Beatrix Layng, led to the death in prison of Thomas Brown, and, in January 1705, the murder of Janet Cornfoot by a lynch mob in the village.

Margaret Aitken, known as the Great Witch of Balwearie, was an important figure in the great Scottish witchcraft panic of 1597 as her actions effectively led to an end of that series of witch trials. After being accused of witchcraft Aitken confessed but then identified hundreds of women as other witches to save her own life. She was exposed as a fraud a few months later and was burnt at the stake.

Beatrix Leslie was a Scottish midwife executed for witchcraft. In 1661 she was accused of causing the collapse of a coal pit through witchcraft. Little is known about her life before that, although there are reported disputes with neighbours that allude to a quarrelsome attitude.

Margaret Burges, also known as 'Lady Dalyell', was a Scottish businesswoman from Nether Cramond who was found guilty of witchcraft and executed in Edinburgh in 1629.

Issobell Young was a wife of a tenant farmer residing in the village of East Barns in the parish of Dunbar, Lothian, Scotland. She was tried, strangled, and burned at the stake at Castle Hill, Edinburgh for practising witchcraft.

The Survey of Scottish Witchcraft is an online database of witch trials in early modern Scotland, containing details of 3,837 accused gathered from contemporary court documents covering the period from 1563 until the repeal of the Scottish Witchcraft Act in 1736. The survey was made available online in 2003 after two years of work at the University of Edinburgh by Julian Goodare, now a professor of history at the University of Edinburgh, and Louise Yeoman, ex-curator at the National Library of Scotland, now a producer/presenter at BBC Radio Scotland, with assistance from researchers Lauren Martin and Joyce Miller, and Computing Services at the University of Edinburgh. The database is available for download from the website.

Julian Goodare is a professor of history at University of Edinburgh.

Louise Yeoman is a historian and broadcaster specialising in the Scottish witch hunts and 17th century Scottish religious beliefs.

The Witches of Bo'ness were a group of women accused of witchcraft in Bo'ness, Scotland in the late 17th century and ultimately executed for this crime. Among the more famous cases noted by historians, in 1679, Margaret Pringle, Bessie Vickar, Annaple Thomsone, and two women both called Margaret Hamilton were all accused of being witches, alongside "warlock" William Craw. The case of these six was "one of the last multiple trials to take place for witchcraft" in Scotland.

Violet Mar was a Scottish woman accused of plotting the death of Regent Morton by witchcraft.

Margaret Barclay, was an accused witch put on trial in 1618, 'gently' tortured, confessed and was strangled and burned at the stake in Irvine, Scotland. Her case was written about with horror by the romantic novelist Sir Walter Scott, and in the 21st century, a campaign for a memorial in the town and for a pardon for Barclay and other accused witches was raised in the Scottish Parliament.

Witches of Scotland was a campaign for legal pardons and historic justice for the people, primarily women, convicted of witchcraft and executed in Scotland between 1563 and 1736. A pardon and an apology was made on 8 March 2022. The aim was also to establish a national memorial for the convicted from the Scottish parliament.

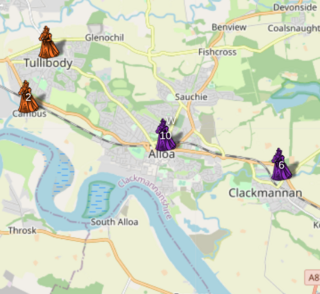

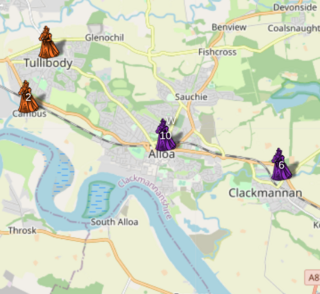

Margaret Duchill was a Scottish woman who confessed to witchcraft at Alloa during the year 1658. She was implicated by others and she named other women. She was executed on 1 June 1658.