John George Phillips, known as Jack Phillips was a British sailor and the senior wireless operator aboard the Titanic during her ill-fated maiden voyage in April 1912.

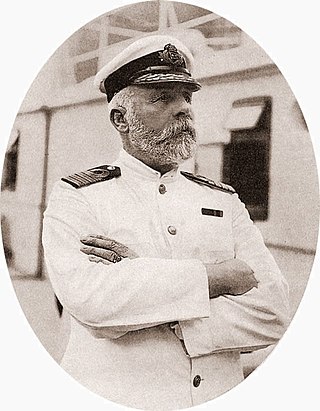

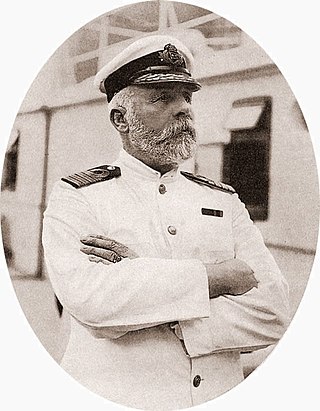

Edward John Smith was a British sea captain and naval officer. In 1880, he joined the White Star Line as an officer, beginning a long career in the British Merchant Navy. Smith went on to serve as the master of numerous White Star Line vessels. During the Second Boer War, he served in the Royal Naval Reserve, transporting British Imperial troops to the Cape Colony. Smith served as captain of the ocean liner Titanic, and went down with the ship when it sank on her maiden voyage.

HMS Birkenhead, also referred to as HM Troopship Birkenhead or Steam Frigate Birkenhead, was one of the first iron-hulled ships built for the Royal Navy. She was designed as a steam frigate, but was converted to a troopship before being commissioned.

William McMaster Murdoch, RNR was a Scottish sailor, who was the first officer on the RMS Titanic. He was the officer in charge on the bridge when the ship collided with an iceberg, and was one of the more than 1,500 people who died when the ship sank.

Titanic is a 1953 American drama film directed by Jean Negulesco and starring Clifton Webb and Barbara Stanwyck. It centers on an estranged couple and other fictional passengers on the ill-fated maiden voyage of the RMS Titanic, which took place in April 1912.

Commander Charles Herbert Lightoller, was a British mariner and naval officer. He was the second officer on board the RMS Titanic and the most senior officer to survive the Titanic disaster. As the officer in charge of loading passengers into lifeboats on the port side, Lightoller strictly enforced the women and children only protocol, not allowing any male passengers to board the lifeboats unless they were needed as auxiliary seamen. Lightoller served as a commanding officer in the Royal Navy during World War I and was twice decorated for gallantry. During World War II, in retirement, he voluntarily provided his personal yacht, the Sundowner, and sailed her as one of the "little ships" that played a part in the Dunkirk evacuation.

Robert Hichens was a British sailor who was part of the deck crew on board the RMS Titanic when she sank on her maiden voyage on 15 April 1912. He was one of seven quartermasters on board the vessel and was at the ship's wheel when the Titanic struck the iceberg. He was in charge of Lifeboat #6, where he refused to return to rescue people from the water due to fear of the boat being sucked into the ocean with the huge suction created by Titanic, or swamped by other floating passengers. According to several accounts of those on the boat, including Margaret Brown, who argued with him throughout the early morning, Lifeboat 6 did not return to save other passengers from the waters. In 1906, he married Florence Mortimore in Devon, England; when he registered for duty aboard the Titanic, his listed address was in Southampton, where he lived with his wife and two children.

Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Godfrey Peuchen was a Canadian businessman and RMS Titanic survivor.

Henry Tingle Wilde, RNR was a British naval officer who was the chief officer of the RMS Titanic. He died when the ship sank on her maiden voyage in April 1912.

James Paul Moody was a British sailor, who served as Titanic's sixth officer. He died when the ship sank on her maiden voyage.

Commander Harold Godfrey Lowe, RD was a Welsh naval officer. He was also the fifth officer of the RMS Titanic, and was amongst the four of the ship's officers to survive the disaster.

A Night to Remember is a 1958 British historical disaster docudrama film based on the eponymous 1955 book by Walter Lord. The film and book recount the final night of RMS Titanic, which sank on her maiden voyage after she struck an iceberg in 1912. Adapted by Eric Ambler and directed by Roy Ward Baker, the film stars Kenneth More as the ship's Second Officer Charles Lightoller and features Michael Goodliffe, Laurence Naismith, Kenneth Griffith, David McCallum and Tucker McGuire. It was filmed in the United Kingdom and tells the story of the sinking, portraying the main incidents and players in a documentary-style fashion with considerable attention to detail. The production team, supervised by producer William MacQuitty used blueprints of the ship to create authentic sets, while Fourth Officer Joseph Boxhall and ex-Cunard Commodore Harry Grattidge worked as technical advisors on the film. Its estimated budget of up to £600,000 was exceptional and made it the most expensive film ever made in Britain up to that time. The film's score was written by William Alwyn.

Archibald Gracie IV was an American writer, soldier, amateur historian, real estate investor, and survivor of the sinking of the Titanic. Gracie survived the sinking by climbing aboard an overturned collapsible lifeboat and wrote a popular book about the disaster. He never recovered from his ordeal and died less than eight months after the sinking, becoming the first adult survivor to die.

RMS Titanic sank in the early morning hours of 15 April 1912 in the North Atlantic Ocean, four days into her maiden voyage from Southampton to New York City. The largest ocean liner in service at the time, Titanic had an estimated 2,224 people on board when she struck an iceberg at around 23:40 on Sunday, 14 April 1912. Her sinking two hours and forty minutes later at 02:20 ship's time on Monday, 15 April, resulted in the deaths of more than 1,500 people, making it one of the deadliest peacetime maritime disasters in history.

Charles John Joughin was a British-American chef, known as being the chief baker aboard the RMS Titanic. He survived the ship's sinking, and became notable for having survived in the frigid water for an exceptionally long time before being pulled onto the overturned Collapsible B lifeboat with virtually no ill effects.

A total of 2,240 people sailed on the maiden voyage of the Titanic, the second of the White Star Line's Olympic-class ocean liners, from Southampton, England, to New York City. Partway through the voyage, the ship struck an iceberg and sank in the early morning of 15 April 1912, resulting in the deaths of 1,517 passengers.

Titanic Lifeboat No. 1 was a lifeboat from the steamship Titanic. It was the fifth boat launched to sea, over an hour after the liner collided with an iceberg and began sinking on 14 April 1912. With a capacity of 40 people, it was launched with only 12 aboard, the fewest to escape in any one boat that night.

"The captain goes down with the ship" is a maritime tradition that a sea captain holds the ultimate responsibility for both the ship and everyone embarked on it, and in an emergency they will devote their time to save those on board or die trying. Although often connected to the sinking of RMS Titanic in 1912 and its captain, Edward Smith, the tradition precedes Titanic by several years. In most instances, captains forgo their own rapid departure of a ship in distress, and concentrate instead on saving other people. It often results in either the death or belated rescue of the captain as the last person on board.

Lifeboats played a crucial role during the sinking of the Titanic on 14–15 April 1912. The ship had 20 lifeboats that, in total, could accommodate 1,178 people, a little over half of the 2,209 on board the night it sank.

The sinking of the RMS Titanic on April 14–15, 1912 resulted in an inquiry by a subcommittee of the Commerce Committee of the United States Senate, chaired by Senator William Alden Smith. The hearings began in New York on April 19, 1912, later moving to Washington, D.C., concluding on May 25, 1912 with a return visit to New York.