The history of Guyana begins about 35,000 years ago with the arrival of humans coming from Eurasia. These migrants became the Carib and Arawak tribes, who met Alonso de Ojeda's first expedition from Spain in 1499 at the Essequibo River. In the ensuing colonial era, Guyana's government was defined by the successive policies of the French, Dutch, and British settlers. During the colonial period, Guyana's economy was focused on plantation agriculture, which initially depended on slave labor. Guyana saw major slave rebellions in 1763 and 1823. Following the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833, 800,000 enslaved Africans in the Caribbean and South Africa were freed, resulting in plantations contracting indentured workers, mainly from India. Eventually, these Indians joined forces with Afro-Guyanese descendants of slaves to demand equal rights in government and society. After the Second World War, the British Empire pursued policy decolonization of its overseas territories, with independence granted to British Guiana on May 26, 1966. Following independence, Forbes Burnham rose to power, quickly becoming an authoritarian leader, pledging to bring socialism to Guyana. His power began to weaken following international attention brought to Guyana in wake of the Jonestown mass murder suicide in 1978.

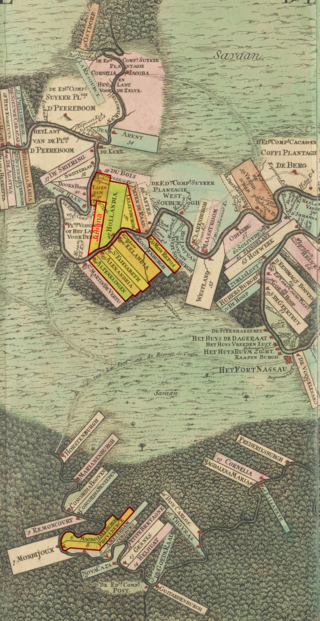

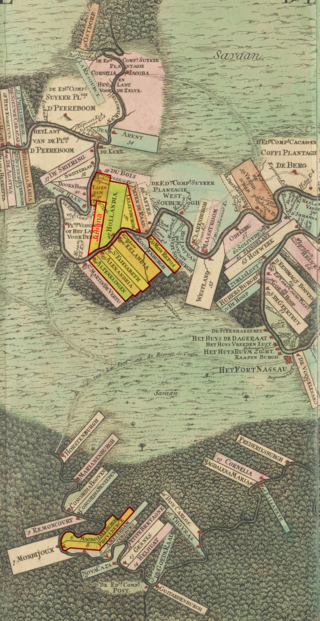

Demerara is a historical region in the Guianas, on the north coast of South America, now part of the country of Guyana. It was a colony of the Dutch West India Company between 1745 and 1792 and a colony of the Dutch state from 1792 until 1815. It was merged with Essequibo in 1812 by the British who took control. It formally became a British colony in 1815 until Demerara-Essequibo was merged with Berbice to form the colony of British Guiana in 1831. In 1838, it became a county of British Guiana until 1958. In 1966, British Guiana gained independence as Guyana and in 1970 it became a republic as the Co-operative Republic of Guyana. It was located around the lower course of the Demerara River, and its main settlement was Georgetown.

The music of Guyana encompasses a range of musical styles and genres that draw from various influences including: Indian, Latino-Hispanic, European, African, Chinese, and Amerindian music. Popular Guyanese performers include: Terry Gajraj, Eddy Grant, Dave Martins & the Tradewinds, Aubrey Cummings, Colle´ Kharis and Nicky Porter. Eddie Hooper The Guyana Music Festival has proven to be influential on the Guyana music scene.

Cuffy, also spelled as Kofi or Koffi, was an Akan man who was captured in his native West Africa and stolen for slavery to work on the plantations of the Dutch colony of Berbice in present-day Guyana. In 1763, he led a major slave revolt of more than 3,800 slaves against the colonial regime. Today, he is a national hero in Guyana.

Islam in Guyana is the third largest religion in the country after Christianity and Hinduism, respectively. According to the 2012 census, 7% of the country’s population is Muslim. However, a Pew Research survey from 2010 estimates that 6.4% of the country is Muslim. Islam was first introduced to Guyana via slaves from West Africa, but was suppressed on plantations until Muslims from British India were brought to the country as indentured labour. The current President of Guyana, Mohamed Irfaan Ali is the first Muslim president.

Rosignol is a village on the west bank of the Berbice River in Mahaica-Berbice, Guyana.

Baracara village was founded by people of African descent in the East Berbice-Corentyne Region of Guyana, located on the Canje River. The community has also been called New Ground Village or Wel te Vreeden. Baracara is 20 miles west of Corriverton and just north of the Torani Canal's connection to the Canje River.

The Mahaica River is a small river in northern Guyana that drains into the Atlantic Ocean. The village of Mahaica is found at its mouth.

The Railways of Guyana comprised two public railways, the Demerara-Berbice Railway and the Demerara-Essequibo Railway. There are also several industrial railways mainly for the bauxite industry. The Demerara-Berbice Railway is the oldest in South America. None of the railways are in operation in the 21st century.

The Berbice slave uprising was a slave revolt in Guyana that began on 23 February 1763 and lasted to December, with leaders including Coffy. The first major slave revolt in South America, it is seen as a major event in Guyana's anti-colonial struggles, and when Guyana became a republic in 1970 the state declared 23 February as a day to commemorate the start of the Berbice slave revolt.

Vreed en Hoop is a village at the mouth of the Demerara River on its west bank, in the Essequibo Islands-West Demerara region of Guyana, located at sea level. It is the location of the Regional Democratic Council office making it the administrative center for the region. There is also a police station, magistrate's court and post office.

Ryhaan Shah is an Indo-Guyanese writer born in Berbice, Guyana. She is active in Guyanese public life as the President of the Guyanese Indian Heritage Association (GIHA).

The people of Guyana, or Guyanese, come from a wide array of backgrounds and cultures including aboriginal natives, African and Indian origins, as well as a minority of Chinese and European descendant peoples. Demographics as of 2012 are Afro-Guyanese 39.8%, Indo-Guyanese 30.1%, mixed race 19.9%, Amerindian 10.5%, other 1.5%. As a result, Guyanese do not equate their nationality with race and ethnicity, but with citizenship. Although citizens make up the majority of Guyanese, there is a substantial number of Guyanese expatriates, dual citizens and descendants living worldwide, chiefly elsewhere in the Anglosphere.

Rockstone is a village on the right bank of the Essequibo River in the Upper Demerara-Berbice Region of Guyana, altitude 6 metres. Rockstone is approximately 26 km west of Linden and is linked by road.

The Demerara rebellion of 1823 was an uprising involving between 9,000 and 12,000 enslaved people that took place in the colony of Demerara-Essequibo (Guyana). The exact number of how many took part in the uprising is a matter of debate. The rebellion, which began on 18 August 1823 and lasted for two days. Their goal was full emancipation. The uprising was triggered by a widespread but mistaken belief that Parliament had passed a law that abolished slavery and that this was being withheld by the colonial rulers. Instigated chiefly by Jack Gladstone, an enslaved man from the "Success" plantation, the rebellion also involved his father, Quamina, and other senior members of their church group. Its English pastor, John Smith, was implicated.

Quamina Gladstone, most often referred to simply as Quamina, was a Guyanese slave from Africa and father of Jack Gladstone. He and his son were involved in the Demerara rebellion of 1823, one of the largest slave revolts in the British colonies before slavery was abolished.

Coromantee, Coromantins, Coromanti or Kormantine is an English-language term for enslaved people from the Akan ethnic group, taken from the Gold Coast region in modern-day Ghana. The term was primarily used in the Caribbean and is now considered archaic.

Mining in Guyana is a significant contributor to the economy owing to sizable reserves of bauxite, gold, and diamonds. Much of these resources are found in Guyana's Hilly Sand and Clay belt, a region that makes up 20% of the country.

Fort Wellington is a village located in the Mahaica-Berbice region of Guyana, serving as its regional capital.