Related Research Articles

Libertarian socialism, also referred to as anarcho-socialism, anarchist socialism, free socialism, stateless socialism, socialist anarchism and socialist libertarianism, is an anti-authoritarian, anti-statist and libertarian political philosophy within the socialist movement which rejects the state socialist conception of socialism as a statist form where the state retains centralized control of the economy. Overlapping with anarchism and libertarianism, libertarian socialists criticize wage slavery relationships within the workplace, emphasizing workers' self-management and decentralized structures of political organization. As a broad socialist tradition and movement, libertarian socialism includes anarchist, Marxist, and anarchist- or Marxist-inspired thought as well as other left-libertarian tendencies. Anarchism and libertarian Marxism are the main currents of libertarian socialism.

The Anarchist Federation is a far left federation of anarcho-communists in Great Britain. It is not a political party, but a direct action, agitational and propaganda organisation.

Shachtmanism is the form of Marxism associated with Max Shachtman (1904–1972). It has two major components: a bureaucratic collectivist analysis of the Soviet Union and a third camp approach to world politics. Shachtmanites believe that the Stalinist rulers of proclaimed socialist countries are a new ruling class distinct from the workers and reject Trotsky's description of Stalinist Russia as a "degenerated workers' state".

Anarchism in the United Kingdom initially developed within the religious dissent movement that began after the Protestant Reformation. Anarchism was first seen among the radical republican elements of the English Civil War and following the Stuart Restoration grew within the fringes of radical Whiggery. The Whig politician Edmund Burke was the first to expound anarchist ideas, which developed as a tendency that influenced the political philosophy of William Godwin, who became the first modern proponent of anarchism with the release of his 1793 book Enquiry Concerning Political Justice.

The history of anarchism is as ambiguous as anarchism itself. Scholars find it hard to define or agree on what anarchism means, which makes outlining its history difficult. There is a range of views on anarchism and its history. Some feel anarchism is a distinct, well-defined 19th and 20th century movement while others identify anarchist traits long before first civilisations existed.

The Zabalaza Anarchist Communist Front, formerly known as the Zabalaza Anarchist Communist Federation (ZabFed), is a platformist–especifista anarchist political organisation in South Africa, based primarily in Johannesburg. The word zabalaza means "struggle" in isiZulu and isiXhosa. Initially, as ZabFed, it was a federation of pre-existing collectives, mainly in Soweto and Johannesburg. It is now a unitary organisation based on individual applications for membership, describing itself as a "federation of individuals". Historically the majority of members have been people of colour. Initially the ZACF had sections in both South Africa and Swaziland. The two sections were split in 2007, but the Swazi group faltered in 2008. Currently the ZACF also recruits in Zimbabwe. Members have historically faced repression in both Swaziland and South Africa.

Anarchism in Africa refers both to purported anarchic political organisation of some traditional African societies and to modern anarchist movements in Africa.

The Japanese Anarchist Federation was an anarchist organisation that existed in Japan from 1946 to 1968.

Anarchism without adjectives, in the words of historian George Richard Esenwein, "referred to an unhyphenated form of anarchism, that is, a doctrine without any qualifying labels such as communist, collectivist, mutualist, or individualist. For others, [...] [it] was simply understood as an attitude that tolerated the coexistence of different anarchist schools".

Libertarian Marxism is a broad scope of economic and political philosophies that emphasize the anti-authoritarian and libertarian aspects of Marxism. Early currents of libertarian Marxism such as left communism emerged in opposition to Marxism–Leninism.

Anarchism is generally defined as the political philosophy which holds the state to be undesirable, unnecessary and harmful as well as opposing authority and hierarchical organization in the conduct of human relations. Proponents of anarchism, known as anarchists, advocate stateless societies based on non-hierarchical voluntary associations. While anarchism holds the state to be undesirable, unnecessary and harmful, opposition to the state is not its central or sole definition. Anarchism can entail opposing authority or hierarchy in the conduct of all human relations.

Anarchism in Sweden first grew out of the nascent social democratic movement during the later 19th century, with a specifically libertarian socialist tendency emerging from a split in the movement. As with the movements in Germany and the Netherlands, Swedish anarchism had a strong syndicalist tendency, which culminated in the establishment of the Central Organisation of the Workers of Sweden (SAC) following an aborted general strike. The modern movement emerged during the late 20th century, growing within a number of countercultural movements before the revival of anarcho-syndicalism during the 1990s.

Anarchism in Ireland has its roots in the stateless organisation of the túatha in Gaelic Ireland. It first began to emerge from the libertarian socialist tendencies within the Irish republican movement, with anarchist individuals and organisations sprouting out of the resurgent socialist movement during the 1880s, particularly gaining prominence during the time of the Dublin Socialist League.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to anarchism, generally defined as the political philosophy which holds the state to be undesirable, unnecessary and harmful, or alternatively as opposing authority and hierarchical organization in the conduct of human relations. Proponents of anarchism, known as anarchists, advocate stateless societies or non-hierarchical voluntary associations.

Libertarianism in the United Kingdom can either refer to a political movement synonymous with anarchism, left-libertarianism and libertarian socialism, or to a political movement concerned with the pursuit of propertarian right-libertarian ideals in the United Kingdom which emerged and became more prominent in British politics after the 1980s neoliberalism and the economic liberalism of the premiership of Margaret Thatcher, albeit not as prominent as libertarianism in the United States in the 1970s and the presidency of Republican Ronald Reagan during the 1980s.

Contemporary anarchism within the history of anarchism is the period of the anarchist movement continuing from the end of World War II and into the present. Since the last third of the 20th century, anarchists have been involved in anti-globalisation, peace, squatter and student protest movements. Anarchists have participated in violent revolutions such as in those that created the Free Territory and Revolutionary Catalonia, and anarchist political organizations such as the International Workers' Association and the Industrial Workers of the World have existed since the 20th century. Within contemporary anarchism, the anti-capitalism of classical anarchism has remained prominent.

Social anarchism, sometimes referred to as red anarchism, is the branch of anarchism that sees individual freedom as interrelated with mutual aid. Social anarchist thought emphasizes community and social equality as complementary to autonomy and personal freedom. It attempts to accomplish this balance through freedom of speech, which is maintained in a decentralized federalism, with freedom of interaction in thought and subsidiarity. Subsidiarity is best defined as "that one should not withdraw from individuals and commit to the community what they can accomplish by their own enterprise and industry" and that "[f]or every social activity ought of its very nature to furnish help to the members of the body social, and never destroy and absorb them", or the slogan "Do not take tools out of people's hands".

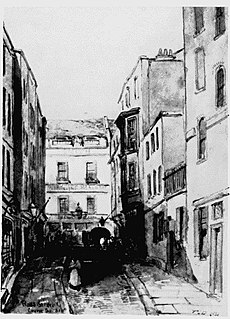

The Rose Street Club was a far-left, anarchist organisation based in what is now Manette Street, London. Originally centred around London's German community, and acting as a meeting point for new immigrants, it became one of the leading radical clubs of Victorian London in the late-nineteenth century. Although its roots went back to the 1840s, it was properly formed in 1877 by members of a German émigré workers' education group, which soon became frequented by London radicals, and within a few years had led to the formation of similar clubs, sometimes in support and sometimes in rivalry. The Rose Street Club provided a platform for the radical speakers and agitators of the day and produced its own paper, Freiheit—which was distributed over Europe, and especially Germany—and pamphlets for other groups and individuals. Although radical, the club initially focused as much on providing a social service to its members as on activism. With the arrival of the anarchist Johann Most in London in the early 1880s, and his increasing influence within the club, it became increasingly aligned with anarchism.

The Anarchist Federation of Britain was a British anarchist organisation that participated in the anti-war movement during World War II, organising a number of strike actions and providing support to conscientious objectors. Over time it gravitated towards anarcho-syndicalism, causing a split in the organisation, with the remnants reconstituting themselves as the Syndicalist Workers Federation.

References

- ↑ Franks 2006, p. 220.

- ↑ Franks 2006, p. 164.

- 1 2 Cross 2014, p. 134; Franks 2006, p. 70.

- ↑ Cross 2014, p. 134.

- 1 2 Franks 2006, p. 70.

- ↑ Cross 2014, pp. 134–135.

- ↑ Franks 2006, pp. 73–74.

- ↑ Cross 2014, p. 135; Franks 2006, p. 74.

- 1 2 Cross 2014, p. 135.

- ↑ Franks 2006, pp. 75–76.

- ↑ Franks 2006, p. 74.

- ↑ Franks 2006, p. 83.