Darwinism is a theory of biological evolution developed by the English naturalist Charles Darwin (1809–1882) and others, stating that all species of organisms arise and develop through the natural selection of small, inherited variations that increase the individual's ability to compete, survive, and reproduce. Also called Darwinian theory, it originally included the broad concepts of transmutation of species or of evolution which gained general scientific acceptance after Darwin published On the Origin of Species in 1859, including concepts which predated Darwin's theories. English biologist Thomas Henry Huxley coined the term Darwinism in April 1860.

Anarchist communism is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private property but retention of personal property and collectively-owned items, goods, and services. It supports social ownership of property and the distribution of resources "From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs".

Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin was a Russian anarchist and geographer known as a proponent of anarchist communism.

Green anarchism, also known as ecological anarchism or eco-anarchism, is an anarchist school of thought that focuses on ecology and environmental issues. It is an anti-capitalist and anti-authoritarian form of radical environmentalism, which emphasises social organization, freedom and self-fulfillment.

Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution is a 1902 collection of anthropological essays by Russian naturalist and anarchist philosopher Peter Kropotkin. The essays, initially published in the English periodical The Nineteenth Century between 1890 and 1896, explore the role of mutually beneficial cooperation and reciprocity in the animal kingdom and human societies both past and present. It is an argument against theories of social Darwinism that emphasize competition and survival of the fittest, and against the romantic depictions by writers such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who thought that cooperation was motivated by universal love. Instead, Kropotkin argues that mutual aid has pragmatic advantages for the survival of human and animal communities and, along with the conscience, has been promoted through natural selection.

A benefit society, fraternal benefit society, fraternal benefit order, friendly society, or mutual aid society is a society, an organization or a voluntary association formed to provide mutual aid, benefit, for instance insurance for relief from sundry difficulties. Such organizations may be formally organized with charters and established customs, or may arise ad hoc to meet unique needs of a particular time and place.

Solidarity or solidarism is an awareness of shared interests, objectives, standards, and sympathies creating a psychological sense of unity of groups or classes. Solidarity does not reject individuals and sees individuals as the basis of society. It refers to the ties in a society that bind people together as one. The term is generally employed in sociology and the other social sciences as well as in philosophy and bioethics. It is a significant concept in Catholic social teaching and in Christian democratic political ideology. Although being interconnected concepts, solidarity, by contrast to charity, takes a systems change approach.

Common ownership refers to holding the assets of an organization, enterprise or community indivisibly rather than in the names of the individual members or groups of members as common property.

Sufra is a community food and support hub based in Stonebridge ward in the London Borough of Brent.

Catholic Relief Services (CRS) is the international humanitarian agency of the Catholic community in the United States. Founded in 1943 by the Bishops of the United States, the agency provides assistance to 130 million people in more than 110 countries and territories in Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and Eastern Europe.

Hunger in the United States of America affects millions of Americans, including some who are middle class, or who are in households where all adults are in work. The United States produces far more food than it needs for domestic consumption—hunger within the U.S. is caused by some Americans having insufficient money to buy food for themselves or their families. Additional causes of hunger and food insecurity include neighborhood deprivation and agricultural policy. Hunger is addressed by a mix of public and private food aid provision. Public interventions include changes to agricultural policy, the construction of supermarkets in underserved neighborhoods, investment in transportation infrastructure, and the development of community gardens. Private aid is provided by food pantries, soup kitchens, food banks, and food rescue organizations.

A community fridge is a refrigerator located in a public space. Sometimes called freedges, they are a type of mutual aid project that enables food to be shared within a community. Some community fridges also have an associated area for non-perishable food. Unlike traditional food pantries, these grassroots projects encourage anyone to put food in and take food out without limit, helping to remove the stigma from its use. The fridges take a decentralized approach, often being maintained by a network of volunteers, community members, local businesses, and larger organizations. Food in community fridges is primarily donated by individuals or food rescue organizations and can be sourced from a variety of places. Major grocers like Trader Joe's and Whole Foods donate large amounts of excess foods to food rescue organizations that then donate to these fridges. The food donated would have otherwise been thrown out.

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted religion in various ways, including the cancellation of the worship services of various faiths and the closure of Sunday schools, as well as the cancellation of pilgrimages, ceremonies and festivals. Many churches, synagogues, mosques, and temples have offered worship through livestream amidst the pandemic, or held interactive sessions on Zoom.

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted inequities experienced by marginalized populations, and has had a significant impact on the LGBT community. Gay pride events were cancelled or postponed worldwide. More than 220 gay pride celebrations around the world were canceled or postponed in 2020, and in response a Global Pride event was hosted online. LGBTQ+ people also tend to be more likely to have pre-existing health conditions, such as asthma, HIV/AIDS, cancer, or obesity, that would worsen their chances of survival if they became infected with COVID-19. They are also more likely to smoke.

The COVID-19 pandemic has greatly impacted the international and domestic economies. Thus, many organizations, private individuals, religious institutions and governments have created different charitable drives, concerts and other events to lessen the economic impact felt.

Both the national government and local governments have responded to the COVID-19 pandemic in the Philippines with various declarations of emergency, closure of schools and public meeting places, lockdowns, and other restrictions intended to slow the spread of the virus.

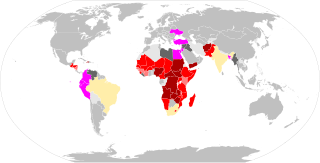

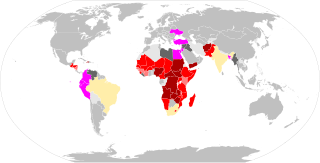

During the COVID-19 pandemic, food insecurity has intensified in many places – in the second quarter of 2020 there were multiple warnings of famine later in the year. In an early report, the Nongovernmental Organization (NGO) Oxfam-International talks about "economic devastation" while the lead-author of the UNU-WIDER report compared COVID-19 to a "poverty tsunami". Others talk about "complete destitution", "unprecedented crisis", "natural disaster", "threat of catastrophic global famine". The decision of WHO on 11 March 2020, to qualify COVID as a pandemic, that is "an epidemic occurring worldwide, or over a very wide area, crossing international boundaries and usually affecting a large number of people" also contributed to building this global-scale disaster narrative.

The United Nations response to the COVID-19 pandemic has been led by its Secretary-General and can be divided into formal resolutions at the General Assembly and at the Security Council (UNSC), and operations via its specialized agencies and chiefly the World Health Organization in the initial stages, but involving more humanitarian-oriented agencies as the humanitarian impact became clearer, and then economic organizations, like the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, the International Labour Organization, and the World Bank, as the socioeconomic implications worsened.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Native American tribes and tribal communities has been severe and has emphasized underlying inequalities in Native American communities compared to the majority of the American population. The pandemic exacerbated existing healthcare and other economic and social disparities between Native Americans and other racial and ethnic groups in the United States. Along with black Americans, Latinos, and Pacific Islanders, the death rate in Native Americans due to COVID-19 was twice that of white and Asian Americans, with Native Americans having the highest mortality rate of all racial and ethnic groups nationwide. As of January 5, 2021, the mortality impact in Native American populations from COVID-19 was 1 in 595 or 168.4 deaths in 100,000, compared to 1 in 1,030 for white Americans and 1 in 1,670 for Asian Americans. Prior to the pandemic, Native Americans were already at a higher risk for infectious disease and mortality than any other group in the United States.

Community pantries in the Philippines are food banks established by Filipinos during the country's COVID-19 community quarantine.