Wang Zhaoming, widely known by his pen name Wang Jingwei, was a Chinese politician. He was initially a member of the left wing of the Kuomintang, leading a government in Wuhan in opposition to the right-wing government in Nanjing, but later became increasingly anti-communist after his efforts to collaborate with the Chinese Communist Party ended in political failure. His political orientation veered sharply to the right later in his career after he collaborated with the Japanese.

Wu Jingheng, commonly known by his courtesy name Wu Zhihui, also known as Wu Shi-Fee, was a Chinese linguist and philosopher who was the chairman of the 1912–13 Commission on the Unification of Pronunciation that created Zhuyin and standardized Guoyu pronunciation.

The Hsing Chung Hui, translated as the Revive China Society (興中會), the Society for Regenerating China, or the Proper China Society was founded by Sun Yat-sen on 24 November 1894 to forward the goal of establishing prosperity for China and as a platform for future revolutionary activities. It was formed during the First Sino-Japanese War, after a string of Chinese military defeats exposed corruption and incompetence within the imperial government of the Qing dynasty. The Revive China Society went through several political re-organizations in later years and eventually became the party known as the Kuomintang. As such, the contemporary Kuomintang considers its founding date to be the establishment of Revive China Society.

Sun Fo or Sun Ke, courtesy name Zhesheng (哲生), was a high-ranking official in the government of the Republic of China. He was the son of Sun Yat-sen, the founder of the Republic of China, and his first wife Lu Muzhen.

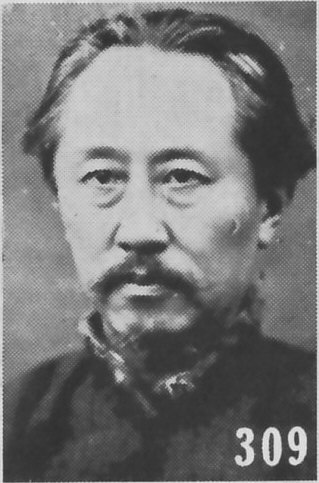

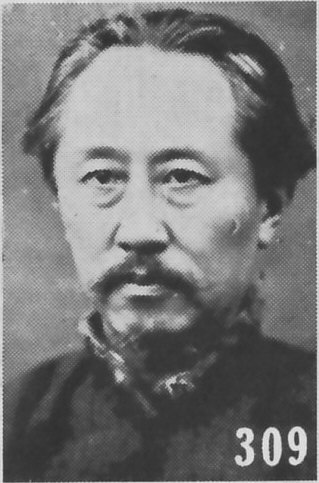

Liu Shifu also known as Sifu, was a Chinese assassin and politician. He was an Esperantist and an influential figure in the Chinese revolutionary movement in the early twentieth century, and in the Chinese anarchist movement in particular. He was a key figure in the movement, particularly in Kwangtung province, and one of the most important organizers in the Chinese anarchist tradition. He is sometimes considered as the Pierre-Joseph Proudhon of China.

The China Zhi Gong Party is one of the eight legally recognized minor political parties in the People's Republic of China that are subservient to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and represented in the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), a principal organization in the CCP's united front strategy. Some scholars have described the Zhi Gong Party as "gathering non-party voices to support the party".

Liao Zhongkai was a Chinese-American Kuomintang leader and financier. He was the principal architect of the first Kuomintang–Chinese Communist Party (KMT–CCP) United Front in the 1920s. He was assassinated in Canton in August 1925.

Anarchism in China was a strong intellectual force in the reform and revolutionary movements in the early 20th century. In the years before and just after the overthrow of the Qing dynasty Chinese anarchists insisted that a true revolution could not be political, replacing one government with another, but had to overthrow traditional culture and create new social practices, especially in the family. "Anarchism" was translated into Chinese as 無政府主義 literally, "the doctrine of no government."

The Constitutional Protection Movement was a series of movements led by Sun Yat-sen to resist the Beiyang government between 1917 and 1922, in which Sun established another government in Guangzhou as a result. It was known as the Third Revolution by the Kuomintang. The constitution that it intended to protect was the Provisional Constitution of the Republic of China. The first movement lasted from 1917 to 1920; the second from 1921 to 1922. An attempted third movement, begun in 1923, ultimately became the genesis for the Northern Expedition in 1926.

The Shanghai massacre of 12 April 1927, the April 12 Purge or the April 12 Incident as it is commonly known in China, was the violent suppression of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) organizations and leftist elements in Shanghai by forces supporting General Chiang Kai-shek and conservative factions in the Kuomintang. Following the incident, conservative KMT elements carried out a full-scale purge of communists in all areas under their control, and violent suppression occurred in Guangzhou and Changsha. The purge led to an open split between left-wing and right-wing factions in the KMT, with Chiang Kai-shek establishing himself as the leader of the right-wing faction based in Nanjing, in opposition to the original left-wing KMT government based in Wuhan, which was led by Wang Jingwei. By 15 July 1927, the Wuhan regime had expelled the Communists in its ranks, effectively一 ending the First United Front, a working alliance of both the KMT and CCP under the tutelage of Comintern agents. For the rest of 1927, the CCP would fight to regain power, beginning the Autumn Harvest Uprising. With the failure and the crushing of the Guangzhou Uprising at Guangzhou however, the power of the Communists was largely diminished, unable to launch another major urban offensive.

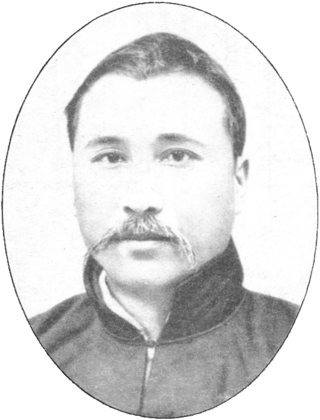

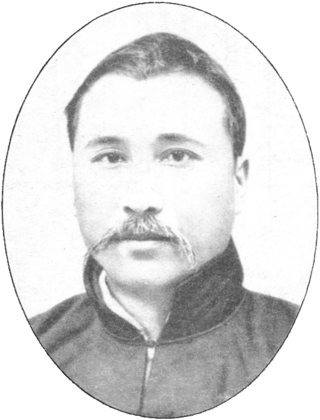

Chen Jiongming, courtesy name Jingcun (竞存/競存), nickname Ayan (阿烟/阿煙), was a Chinese lawyer, military general, revolutionary, anarchist and politician who was best known as a Hailufeng Hokkien revolutionary figure in the early period of the Republic of China.

SS Zhongshan, formerly romanized as Chung Shan, was a Chinese gunboat built in Japan in 1913. It was originally known as SS Yongfeng, before being renamed in 1925 in honor of Sun Yat-sen. Zhongshan was sunk by the Imperial Japanese Navy during the Second Sino-Japanese War, but was later raised and restored as a museum ship in Wuhan.

Anarchism in Vietnam first emerged in the early twentieth century, as the Vietnameses started to fight against their colonial government along with the puppet feudal dynasty for either independence or higher autonomy. Some famous radical figures such as Phan Bội Châu and Nguyễn An Ninh became exposed to strands of anarchism in Japan, China and France. Anarchism reached its apex in Vietnam during the 1920s, but it soon began to lose its influence with the introduction of Marxism-Leninism and the beginning of the Vietnamese communist movement. In recent years, Anarchism in Vietnam has attracted new adherents.

The Yunnan–Guangxi War was a war of succession fought for control of the Chinese Nationalist Party after the death of Sun Yat-sen in 1925. It was launched by the Yunnan clique against the party leadership and the New Guangxi clique.

Li Jishen or Li Chi-shen was a Chinese military officer and politician, general of the National Revolutionary Army of the Republic of China, Vice President of the People's Republic of China (1949–1954), Vice Chairman of the National People's Congress (1954–1959), Vice Chairman the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (1949–1959) and founder and first Chairman of the Revolutionary Committee of the Kuomintang (1948–1959).

Zhang Renjie, born Zhang Jingjiang, was a political figure and financial entrepreneur in the Republic of China. He studied and worked in France in the early 1900s, where he became an early Chinese Anarchist under the influence of Li Shizeng and Wu Zhihui, his lifelong friends. He became wealthy trading Chinese artworks in the West and investing on the Shanghai stock exchange. Zhang gave generous financial support to Sun Yat-sen and was an early patron of Chiang Kai-shek. In the 1920s, he, Li, Wu and the educator Cai Yuanpei were known as the fiercely anti-Communist Four Elders of the Chinese Nationalist Party.

Li Shizeng, born Li Yuying, was an educator, promoter of anarchist doctrines, political activist, and member of the Chinese Nationalist Party in early Republican China.

Socialism in Hong Kong is a political trend taking root from Marxism and Leninism which was imported to Hong Kong in the early 1920s. Socialist trends have taken various forms, including Marxism–Leninism, Maoism, Trotskyism, democratic socialism and liberal socialism, with the Marxist–Leninists being the most dominant faction due to the influence of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) regime in the mainland. The "traditional leftists" became the largest force representing the pro-Beijing camp in the post-war decades, which had an uneasy relationship with the colonial authorities. As the Chinese Communist Party adopted capitalist economic reforms from 1978 onwards and the pro-Beijing faction became increasingly conservative, the socialist agenda has been slowly taken up by the liberal-dominated pro-democratic camp.

Cantonese nationalism is a political movement which supports the independence of Guangdong or Cantonese-majority areas from China. These movements wanted to establish an independent or autonomous political entity. In modern China, this idea has been put forward by others including Kang Youwei's followers and Ou Jujia. Kang Youwei's followers later opposed the claim. In his book "New Guangdong", Ou put forward the idea of establishing "Guangdong of Guangdong". In 1911, there was a revolution. At the end of October 1911, members of the Guangdong Alliance Chen Jiongming, Deng Jun and Peng Ruihai organized civil army uprisings throughout Guangdong. On November 9, Chen Jiongming led his troops to restore Huizhou. On the same day, Guangdong announced independence and established the Guangdong Military Government of the Republic of China. On January 1, 1912, the Republic of China was established, and Guangdong Province became a province in the Republic of China. In the early years of the Republic of China Guangdong Province drafted the "Guangdong Provincial Draft". This is inspired by the idea of autonomous provinces. The draft passed by the Guangdong Provincial Assembly on December 19, 1921. However, this proposal for the future planning of Guangdong Province did not receive sufficient support, and it was aborted as the Soviet forces intervened in the Far East and the KMT and the Communist Party went northward.

Anarchism in Malaysia arose from the revolutionary activities of Chinese immigrants in British Malaya, who were the first to construct an organized anarchist movement in the country - reaching its peak during the 1920s. After a campaign of repression by the British authorities, anarchism was supplanted by Bolshevism as the leading revolutionary current, until the resurgence of the anarchist movement during the 1980s, as part of the Malaysian punk scene.