Libertarian socialism, also referred to as anarcho-socialism, anarchist socialism, free socialism, stateless socialism, socialist anarchism and socialist libertarianism, is an anti-authoritarian, anti-statist and libertarian political philosophy within the socialist movement which rejects the state socialist conception of socialism as a statist form where the state retains centralized control of the economy. Overlapping with anarchism and libertarianism, libertarian socialists criticize wage slavery relationships within the workplace, emphasizing workers' self-management and decentralized structures of political organization. As a broad socialist tradition and movement, libertarian socialism includes anarchist, Marxist and anarchist or Marxist-inspired thought as well as other left-libertarian tendencies. Anarchism and libertarian Marxism are the main currents of libertarian socialism.

Syndicalism is a current in the labor movement to establish local, worker-based organizations and advance the demands and rights of workers through strikes. Most active in the early 20th century, syndicalism was predominant in the revolutionary left in the decade which preceded the outbreak of World War I because orthodox Marxism was mostly reformist at that time, according to the Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm.

Anarcho-syndicalism is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that views revolutionary industrial unionism or syndicalism as a method for workers in capitalist society to gain control of an economy and thus control influence in broader society. The end goal of syndicalism is to abolish the wage system, regarding it as wage slavery. Anarcho-syndicalist theory therefore generally focuses on the labour movement.

Anarchism in Africa refers both to purported anarchic political organisation of some traditional African societies and to modern anarchist movements in Africa.

The Japanese Anarchist Federation was an anarchist organisation that existed in Japan from 1946 to 1968.

Anarchism in South Africa dates to the 1880s, and played a major role in the labour and socialist movements from the turn of the twentieth century through to the 1920s. The early South African anarchist movement was strongly syndicalist. The ascendance of Marxism–Leninism following the Russian Revolution, along with state repression, resulted in most of the movement going over to the Comintern line, with the remainder consigned to irrelevance. There were slight traces of anarchist or revolutionary syndicalist influence in some of the independent left-wing groups which resisted the apartheid government from the 1970s onward, but anarchism and revolutionary syndicalism as a distinct movement only began re-emerging in South Africa in the early 1990s. It remains a minority current in South African politics.

Italian anarchism as a movement began primarily from the influence of Mikhail Bakunin, Giuseppe Fanelli, and Errico Malatesta. Rooted in collectivist anarchism, it expanded to include illegalist individualist anarchism, mutualism, anarcho-syndicalism, and especially anarcho-communism. It participated in the biennio rosso and survived Italian fascism. Platformism and insurrectionary anarchism were particularly common in Italian anarchism and continue to influence the movement today. The synthesist Italian Anarchist Federation appeared after the war, and autonomismo and operaismo especially influenced Italian anarchism in the second half of the 20th century.

Anarchism in Australia arrived within a few years of anarchism developing as a distinct tendency in the wake of the 1871 Paris Commune. Although a minor school of thought and politics, composed primarily of campaigners and intellectuals, Australian anarchism has formed a significant current throughout the history and literature of the colonies and nation. Anarchism's influence has been industrial and cultural, though its influence has waned from its high point in the early 20th century where anarchist techniques and ideas deeply influenced the official Australian union movement. In the mid 20th century anarchism's influence was primarily restricted to urban bohemian cultural movements. In the late 20th century and early 21st century Australian anarchism has been an element in Australia's social justice and protest movements.

Anarchism in Japan began to emerge in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as Western anarchist literature began to be translated into Japanese. It existed throughout the 20th century in various forms, despite repression by the state that became particularly harsh during the two world wars, and it reached its height in the 1920s with organisations such as Kokuren and Zenkoku Jiren.

Anarchism in Poland first developed at the turn of the 20th century under the influence of anarchist ideas from Western Europe and from Russia.

Contemporary anarchism within the history of anarchism is the period of the anarchist movement continuing from the end of World War II and into the present. Since the last third of the 20th century, anarchists have been involved in anti-globalisation, peace, squatter and student protest movements. Anarchists have participated in violent revolutions such as in the Free Territory and Revolutionary Catalonia and anarchist political organizations such as the International Workers' Association and the Industrial Workers of the World exist since the 20th century. Within contemporary anarchism, the anti-capitalism of classical anarchism has remained prominent.

Anarcho-Syndicalism: Theory and Practice. An Introduction to a Subject Which the Spanish War Has Brought into Overwhelming Prominence is a book written by the German anarchist Rudolf Rocker. Its first edition was published by Secker and Warburg, London in 1938 and was translated from Ray E. Chase. Rocker penned this political and philosophical work in 1937, at the behest of Emma Goldman, as an introduction to the ideals fueling the Spanish social revolution and resistance to capitalism and fascism the world over. Within, Rocker offers an introduction to anarchist ideas, a history of the international workers' movement, and an outline of the syndicalist strategies and tactics embraced at the time. The Pluto Press and the newest AK Press editions including a lengthy introduction by Nicolas Walter and a preface by Noam Chomsky. An abridged version was published in the 1950s as Anarchism and Anarcho-Syndicalism.

Types of socialism include a range of economic and social systems characterised by social ownership and democratic control of the means of production and organizational self-management of enterprises as well as the political theories and movements associated with socialism. Social ownership may refer to forms of public, collective or cooperative ownership, or to citizen ownership of equity in which surplus value goes to the working class and hence society as a whole. There are many varieties of socialism and no single definition encapsulates all of them, but social ownership is the common element shared by its various forms. Socialists disagree about the degree to which social control or regulation of the economy is necessary, how far society should intervene, and whether government, particularly existing government, is the correct vehicle for change.

Social anarchism is the branch of anarchism that sees individual freedom as interrelated with mutual aid. Social anarchist thought emphasizes community and social equality as complementary to autonomy and personal freedom. It attempts to accomplish this balance through freedom of speech, which is maintained in a decentralized federalism, with freedom of interaction in thought and subsidiarity. Subsidiarity is best defined as "that one should not withdraw from individuals and commit to the community what they can accomplish by their own enterprise and industry" and that "[f]or every social activity ought of its very nature to furnish help to the members of the body social, and never destroy and absorb them", or the slogan "Do not take tools out of people's hands".

Collectivist anarchism, also referred to as anarchist collectivism and anarcho-collectivism, is a revolutionary socialist doctrine and anarchist school of thought that advocates the abolition of both the state and private ownership of the means of production as it envisions in its place the means of production being owned collectively whilst controlled and self-managed by the producers and workers themselves. Notwithstanding the name, collectivism anarchism is seen as a blend of individualism and collectivism.

Anarchism in Panama began as an organized movement among immigrant workers, brought to the country to work on the numerous megaprojects throughout its history.

Anarchism in Bangladesh has its roots in the ideas of the Bengali Renaissance and began to take influence as part of the revolutionary movement for Indian independence in Bengal. After a series of defeats of the revolutionary movement and the rise of state socialist ideas within the Bengali left-wing, anarchism went into a period of remission. This lasted until the 1990s, when anarchism again began to reemerge after the fracturing of the Communist Party of Bangladesh, which led to the rise of anarcho-syndicalism among the Bangladeshi workers' movement.

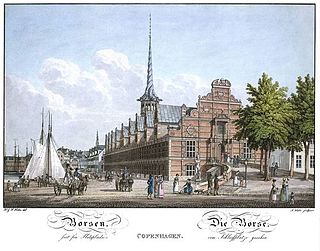

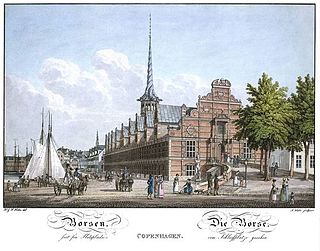

The Storm on the Stock Exchange was a violent attack on the Børsen in Copenhagen on 11 February 1918. The attack was organized by unemployed syndicalists.

Anarchism in Austria first developed from the anarchist segments of the International Workingmen's Association (IWA), eventually growing into a nationwide anarcho-syndicalist movement that reached its height during the 1920s. Following the institution of fascism in Austria and the subsequent war, the anarchist movement was slow to recover, eventually reconstituting anarcho-syndicalism by the 1990s.