Anarcho-syndicalism is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that views revolutionary industrial unionism or syndicalism as a method for workers in capitalist society to gain control of an economy and thus control influence in broader society. The end goal of syndicalism is to abolish the wage system, regarding it as wage slavery. Anarcho-syndicalist theory generally focuses on the labour movement. Reflecting the anarchist philosophy from which it draws its primary inspiration, anarcho-syndicalism is centred on the idea that power corrupts and that any hierarchy that cannot be ethically justified must be dismantled.

The Iberian Anarchist Federation is a Spanish organization of anarchist militants active within affinity groups in the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT) anarcho-syndicalist union. It is often abbreviated as CNT-FAI because of the close relationship between the two organizations. The FAI publishes the periodical Tierra y Libertad.

Sébastien Faure was a French anarchist, convicted sex offender, freethought and secularist activist and a principal proponent of synthesis anarchism.

José Peirats Valls (1908–1989) was a Spanish anarchist, activist, journalist and historian.

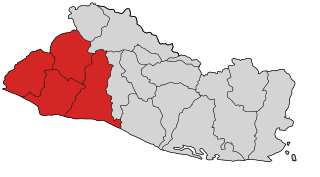

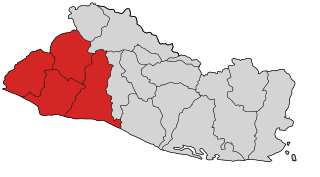

La Matanza refers to a communist-indigenous rebellion that took place in El Salvador between 22 and 25 January 1932. It was succeeded by large-scale government killings in western El Salvador, which resulted in the deaths of 10,000 to 40,000 people.

Anarchism as a social movement in Cuba held great influence with the working classes during the 19th and early 20th century. The movement was particularly strong following the abolition of slavery in 1886, until it was repressed first in 1925 by President Gerardo Machado, and more thoroughly by Fidel Castro's Marxist–Leninist government following the Cuban Revolution in the late 1950s. Cuban anarchism mainly took the form of anarcho-collectivism based on the works of Mikhail Bakunin and, later, anarcho-syndicalism. The Latin American labor movement, and by extension the Cuban labor movement, was at first more influenced by anarchism than Marxism.

The Argentinian anarchist movement was the strongest such movement in South America. It was strongest between 1890 and the start of a series of military governments in 1930. During this period, it was dominated by anarchist communists and anarcho-syndicalists. The movement's theories were a hybrid of European anarchist thought and local elements, just as it consisted demographically of both European immigrant workers and native Argentinians.

Anarchism in Ecuador appeared at the end of the 19th century. At the beginning of the 20th century it started to gain influence in sectors of organized workers and intellectuals.

The Salvadoran military dictatorship was the period of time in Salvadoran history where the Salvadoran Armed Forces governed the country for almost 48 years from 2 December 1931 until 15 October 1979. The authoritarian military dictatorship limited political rights throughout the country and maintained its governance through rigged and fixed elections.

Anarchism in Bolivia has a relatively short but rich history, spanning over a hundred years, primarily linked to syndicalism, the peasantry, and various social movements. Its heyday was during the 20th century's first decades, between 1910 and 1930, but a number of contemporary movements still exist.

Anarchism in Venezuela has historically played a fringe role in the country's politics, being consistently smaller and less influential than equivalent movements in much of the rest of South America. It has, however, had a certain impact on the country's cultural and political evolution.

Lola (Dolores) Iturbe was a prominent Spanish anarcho-syndicalist, trade unionist, activist, and journalist during the Second Spanish Republic, and a member of the French Resistance during the Battle of France. She co-founded the anarcho-feminist movement, Mujeres Libres, and of the Comité de Milicias Antifascistas during the Spanish Civil War.

The anarchist movement in Chile emerged from European immigrants, followers of Mikhail Bakunin affiliated with the International Workingmen's Association, who contacted Manuel Chinchilla, a Spaniard living in Iquique. Their influence could be perceived at first within the labour unions of typographers, painters, builders and sailors. During the first decades of the 20th century, anarchism had a significant influence on the labour movement and intellectual circles of Chile. Some of the most prominent Chilean anarchists were: the poet Carlos Pezoa Véliz, the professor Dr Juan Gandulfo, the syndicalist workers Luis Olea, Magno Espinoza, Alejandro Escobar y Carballo, Ángela Muñoz Arancibia, Juan Chamorro, Armando Triviño and Ernesto Miranda, the teacher Flora Sanhueza, and the writers José Domingo Gómez Rojas, Fernando Santiván, José Santos González Vera and Manuel Rojas. At the moment, anarchist groups are experiencing a comeback in Chile through various student collectives, affinity groups, community and cultural centres, and squatting.

The Palm Sunday Coup was an attempted military coup d'état in El Salvador which occurred in early-April 1944. The coup was staged by pro-Axis sympathizers in the Salvadoran Army against President General Maximiliano Hernández Martínez.

Anarchism in Colombia was a political movement that emerged from the disparate social movements of the 19th-century, becoming an organized force in the 1910s and 1920s. After a period of recession, the movement re-emerged in the late 20th century, with the rise of counter-cultural, left-wing and indigenous resistance movements.

Anarchism in Panama began as an organized movement among immigrant workers, brought to the country to work on the numerous megaprojects throughout its history.

Anarchism in Costa Rica emerged in the 1890s, when it first came to the attention of the country's ruling elites, including the Catholic Church.

Anarchism in Nicaragua emerged during the United States occupation of Nicaragua, when the workers' movement was first organized against the interests of foreign capital. This led to a synthesis of Latin American anarchism with the goals of national liberation, which influenced the early Sandinista movement.

Anarchism in the Dominican Republic first surfaced in the late 19th century, as part of the nascent workers' movement.

Anarchism in Guatemala emerged from the country's labor movement in the late 19th century. Anarcho-syndicalism rose to prominence in the early 20th century, reaching its peak during the 1920s, before being suppressed by the right-wing dictatorship of Jorge Ubico.