Leninism is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary vanguard party as the political prelude to the establishment of communism. Lenin's ideological contributions to the Marxist ideology relate to his theories on the party, imperialism, the state, and revolution. The function of the Leninist vanguard party is to provide the working classes with the political consciousness and revolutionary leadership necessary to depose capitalism.

Otto Bauer was one of the founders and leading thinkers of the left-socialist Austromarxists who sought a middle ground between social democracy and revolutionary socialism. He was a member of the Austrian Parliament from 1907 to 1934, deputy party leader of the Social Democratic Workers' Party (SDAP) from 1918 to 1934, and Foreign Minister of the Republic of German-Austria in 1918 and 1919. In the latter position he worked unsuccessfully to bring about the unification of Austria and the Weimar Republic. His opposition to the SDAP joining coalition governments after it lost its leading position in Parliament in 1920 and his practice of advising the party to wait for the proper historical circumstances before taking action were criticized by some for facilitating Austria's move from democracy to fascism in the 1930s. When the SDAP was outlawed by Austrofascist Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg in 1934, Bauer went into exile where he continued to work for Austrian socialism until his death.

The International Working Union of Socialist Parties was a political international for the co-operation of socialist parties.

The Social Democratic Workers' Party of Germany was a Marxist socialist political party in the North German Confederation during unification.

Max Adler was an Austrian jurist, politician and social philosopher; his theories were of central importance to Austromarxism. He was a brother of Oskar Adler.

Carl Grünberg was a German-Austrian Marxist philosopher of law and history.

National personal autonomy is one form of non-territorial autonomy that grew out of autonomy ideas developed by Austromarxist thinkers.

Marxism is a method of socioeconomic analysis that originates in the works of 19th century German philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Marxism analyzes and critiques the development of class society and especially of capitalism as well as the role of class struggles in systemic, economic, social and political change. It frames capitalism through a paradigm of exploitation and analyzes class relations and social conflict using a materialist interpretation of historical development – materialist in the sense that the politics and ideas of an epoch are determined by the way in which material production is carried on.

Internationalist and defencist were the broad opposing camps in the international socialist movement during and shortly after the First World War. Prior to 1914, anti-militarism had been an article of faith among most European socialist parties. Leaders of the Second International had even suggested that socialist workers might foil a declaration of war by means of a general strike.

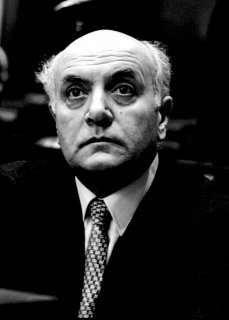

Rudolf Hilferding was an Austrian-born Marxist economist, socialist theorist, politician and the chief theoretician for the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) during the Weimar Republic, being almost universally recognized as the SPD's foremost theoretician of this century. He was also a physician.

The Social Democratic Party of Austria is a social-democratic political party in Austria. Founded in 1889 as the Social Democratic Workers' Party of Austria and later known as the Socialist Party of Austria from 1945 until 1991, the party is the oldest extant political party in Austria. Along with the Austrian People's Party (ÖVP), it is one of the country's two traditional major parties. It is positioned on the centre-left on the political spectrum.

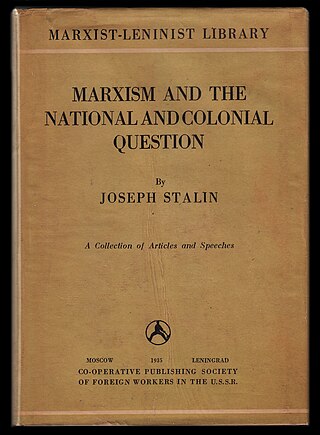

Marxism and the National Question is a short work of Marxist theory written by Joseph Stalin in January 1913 while living in Vienna. First published as a pamphlet and frequently reprinted, the essay by the ethnic Georgian Stalin was regarded as a seminal contribution to Marxist analysis of the nature of nationality and helped to establish his reputation as an expert on the topic. Stalin would later become the first People's Commissar of Nationalities following the victory of the Bolshevik Party in the October Revolution of 1917.

Eurocommunism was a trend in the 1970s and 1980s within various Western European communist parties which said they had developed a theory and practice of social transformation more relevant for Western Europe. During the Cold War, they sought to reject the influence of the Soviet Union and the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. The trend was especially prominent in Italy, Spain, and France.

Friedrich Wolfgang "Fritz" Adler was an Austrian socialist politician, physicist, philosopher and journalist. He is perhaps best known for his assassination of Minister-President Karl von Stürgkh in 1916.

Revolutionary socialism is a political philosophy, doctrine, and tradition within socialism that stresses the idea that a social revolution is necessary to bring about structural changes in society. More specifically, it is the view that revolution is a necessary precondition for transitioning from a capitalist to a socialist mode of production. Revolution is not necessarily defined as a violent insurrection; it is defined as a seizure of political power by mass movements of the working class so that the state is directly controlled or abolished by the working class as opposed to the capitalist class and its interests.

In Marxist philosophy, the dictatorship of the proletariat is a condition in which the proletariat holds state power. The dictatorship of the proletariat is the intermediate stage between a capitalist economy and a communist economy, whereby the post-revolutionary state seizes the means of production, compels the implementation of direct elections on behalf of and within the confines of the ruling proletarian state party, and institutes elected delegates into representative workers' councils that nationalise ownership of the means of production from private to collective ownership. During this phase, the administrative organizational structure of the party is to be largely determined by the need for it to govern firmly and wield state power to prevent counterrevolution and to facilitate the transition to a lasting communist society.

Orthodox Marxism is the body of Marxist thought which emerged after the death of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in the late 19th century, expressed in its primary form by Karl Kautsky. Kautsky's views of Marxism dominated the European Marxist movement for two decades, and orthodox Marxism was the official philosophy of the majority of the socialist movement as represented in the Second International until the First World War in 1914, whose outbreak caused Kautsky's influence to wane and brought to prominence the orthodoxy of Vladimir Lenin. Orthodox Marxism aimed to simplify, codify and systematize Marxist method and theory by clarifying perceived ambiguities and contradictions in classical Marxism.

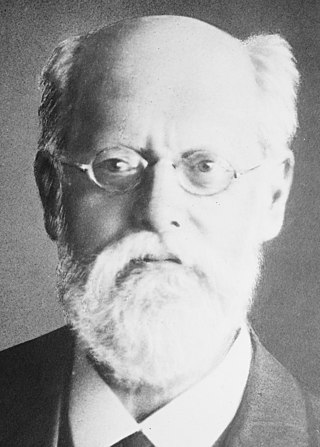

Karl Johann Kautsky was a Czech-Austrian philosopher, journalist, and Marxist theorist. A leading theorist of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and the Second International, Kautsky advocated orthodox Marxism, which emphasized the scientific, materialist, and determinist character of Karl Marx's work. This interpretation dominated European Marxism for two decades, from the death of Friedrich Engels in 1895 to the outbreak of World War I in 1914.

Social democracy originated as an ideology within the labour whose goals have been a social revolution to move away from purely laissez-faire capitalism to a social capitalism model sometimes called a social market economy. In a nonviolent revolution as in the case of evolutionary socialism, or the establishment and support of a welfare state. Its origins lie in the 1860s as a revolutionary socialism associated with orthodox Marxism. Starting in the 1890s, there was a dispute between committed revolutionary social democrats such as Rosa Luxemburg and reformist social democrats. The latter sided with Marxist revisionists such as Eduard Bernstein, who supported a more gradual approach grounded in liberal democracy and cross-class cooperation. Karl Kautsky represented a centrist position. By the 1920s, social democracy became the dominant political tendency, along with communism, within the international socialist movement, representing a form of democratic socialism with the aim of achieving socialism peacefully. By the 1910s, social democracy had spread worldwide and transitioned towards advocating an evolutionary change from capitalism to socialism using established political processes such as the parliament. In the late 1910s, socialist parties committed to revolutionary socialism renamed themselves as communist parties, causing a split in the socialist movement between these supporting the October Revolution and those opposing it. Social democrats who were opposed to the Bolsheviks later renamed themselves as democratic socialists in order to highlight their differences from communists and later in the 1920s from Marxist–Leninists, disagreeing with the latter on topics such as their opposition to liberal democracy whilst sharing common ideological roots.

Der Kampf was a monthly political magazine published in the period between 1907 and 1938. It was first headquartered in Vienna and then in Prague and Brno. It was affiliated with the Austrian Social Democratic Party (SDAP), and its subtitle was Sozialdemokratische Monatsschrift.