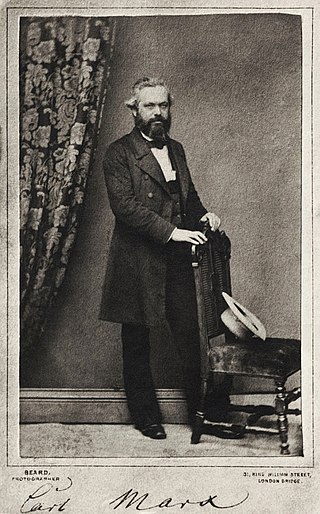

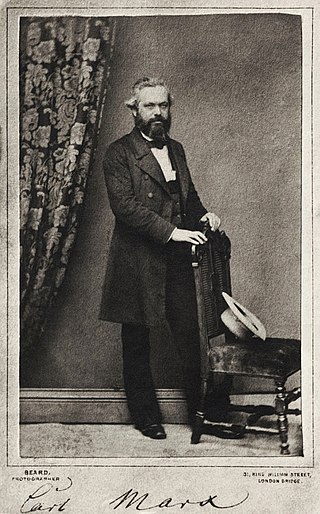

Marxism is a method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialectical perspective to view social transformation. It originates from the works of 19th-century German philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. As Marxism has developed over time into various branches and schools of thought, no single, definitive Marxist theory exists. Marxism has had a profound impact in shaping the modern world, with various left-wing to far-left political movements taking inspiration from it in varying local contexts.

The critique of ideology is a concept used in critical theory, literary studies, and cultural studies. It focuses on analyzing the ideology found in cultural texts, whether those texts be works of popular culture or high culture, philosophy or TV advertisements. These ideologies can be expressed implicitly or explicitly. The focus is on analyzing and demonstrating the underlying ideological assumptions of the texts and then criticizing the attitude of these works. An important part of ideology critique has to do with “looking suspiciously at works of art and debunking them as tools of oppression”.

Marxian class theory asserts that an individual's position within a class hierarchy is determined by their role in the production process, and argues that political and ideological consciousness is determined by class position. A class is those who share common economic interests, are conscious of those interests, and engage in collective action which advances those interests. Within Marxian class theory, the structure of the production process forms the basis of class construction.

Marxism is a method of socioeconomic analysis that originates in the works of 19th century German philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Marxism analyzes and critiques the development of class society and especially of capitalism as well as the role of class struggles in systemic, economic, social and political change. It frames capitalism through a paradigm of exploitation and analyzes class relations and social conflict using a materialist interpretation of historical development – materialist in the sense that the politics and ideas of an epoch are determined by the way in which material production is carried on.

Marxist humanism is an international body of thought and political action rooted in a humanist interpretation of the works of Karl Marx. It is an investigation into "what human nature consists of and what sort of society would be most conducive to human thriving" from a critical perspective rooted in Marxist philosophy. Marxist humanists argue that Marx himself was concerned with investigating similar questions.

In Marxist philosophy, reification is the "conversion of the subject to an object, as when the worker becomes a commodity", or the process by which human social relations are perceived as inherent attributes of the people involved in them, or attributes of some product of the relation, such as a traded commodity.

Structural Marxism is an approach to Marxist philosophy based on structuralism, primarily associated with the work of the French philosopher Louis Althusser and his students. It was influential in France during the 1960s and 1970s, and also came to influence philosophers, political theorists and sociologists outside France during the 1970s. Other proponents of structural Marxism were the sociologist Nicos Poulantzas and the anthropologist Maurice Godelier. Many of Althusser's students broke with structural Marxism in the late 1960s and 1970s.

In Marxism, class consciousness is the set of beliefs that a person holds regarding their social class or economic rank in society, the structure of their class, and their class interests. According to Karl Marx, it is an awareness that is key to sparking a revolution that would "create a dictatorship of the proletariat, transforming it from a wage-earning, property-less mass into the ruling class".

The correct place of Karl Marx's early writings within his system as a whole has been a matter of great controversy. Some believe there is a break in Marx's development that divides his thought into two periods: the "Young Marx" is said to be a thinker who deals with the problem of alienation, while the "Mature Marx" is said to aspire to a scientific socialism.

In Marxist theory, society consists of two parts: the base and superstructure. The base refers to the mode of production which includes the forces and relations of production into which people enter to produce the necessities and amenities of life. The superstructure refers to society's other relationships and ideas not directly relating to production including its culture, institutions, roles, rituals, religion, media, and state. The relation of the two parts is not strictly unidirectional. The superstructure can affect the base. However, the influence of the base is predominant.

Classical Marxism is the body of economic, philosophical, and sociological theories expounded by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in their works, as contrasted with orthodox Marxism, Marxism–Leninism, and autonomist Marxism which emerged after their deaths. The core concepts of classical Marxism include alienation, base and superstructure, class consciousness, class struggle, exploitation, historical materialism, ideology, revolution; and the forces, means, modes, and relations of production. Marx's political praxis, including his attempt to organize a professional revolutionary body in the First International, often served as an area of debate for subsequent theorists.

In Marxist philosophy, the dictatorship of the proletariat is a condition in which the proletariat holds state power. The dictatorship of the proletariat is the intermediate stage between a capitalist economy and a communist economy, whereby the post-revolutionary state seizes the means of production, compels the implementation of direct elections on behalf of and within the confines of the ruling proletarian state party, and instituting elected delegates into representative workers' councils that nationalise ownership of the means of production from private to collective ownership. During this phase, the administrative organizational structure of the party is to be largely determined by the need for it to govern firmly and wield state power to prevent counterrevolution and to facilitate the transition to a lasting communist society. Other terms commonly used to describe the dictatorship of the proletariat include socialist state, proletarian state, democratic proletarian state, revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat and democratic dictatorship of the proletariat. In Marxist philosophy, the term dictatorship of the bourgeoisie is the antonym to the dictatorship of the proletariat.

Marxist philosophy or Marxist theory are works in philosophy that are strongly influenced by Karl Marx's materialist approach to theory, or works written by Marxists. Marxist philosophy may be broadly divided into Western Marxism, which drew from various sources, and the official philosophy in the Soviet Union, which enforced a rigid reading of Marx called dialectical materialism, in particular during the 1930s. Marxist philosophy is not a strictly defined sub-field of philosophy, because the diverse influence of Marxist theory has extended into fields as varied as aesthetics, ethics, ontology, epistemology, social philosophy, political philosophy, the philosophy of science, and the philosophy of history. The key characteristics of Marxism in philosophy are its materialism and its commitment to political practice as the end goal of all thought. The theory is also about the struggles of the proletariat and their reprimand of the bourgeoisie.

György Lukács was a Hungarian Marxist philosopher, literary historian, literary critic, and aesthetician. He was one of the founders of Western Marxism, an interpretive tradition that departed from the Soviet Marxist ideological orthodoxy. He developed the theory of reification, and contributed to Marxist theory with developments of Karl Marx's theory of class consciousness. He was also a philosopher of Leninism. He ideologically developed and organised Lenin's pragmatic revolutionary practices into the formal philosophy of vanguard-party revolution.

Dialectical materialism is a materialist theory based upon the writings of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels that has found widespread applications in a variety of philosophical disciplines ranging from philosophy of history to philosophy of science. As a materialist philosophy, Marxist dialectics emphasizes the importance of real-world conditions and the presence of functional contradictions within and among social relations, which derive from, but are not limited to the contradictions that occur in social class, labour economics, and socioeconomic interactions.

Western Marxism is a current of Marxist theory that arose from Western and Central Europe in the aftermath of the 1917 October Revolution in Russia and the ascent of Leninism. The term denotes a loose collection of theorists who advanced an interpretation of Marxism distinct from both classical and Orthodox Marxism and the Marxism-Leninism of the Soviet Union.

History and Class Consciousness: Studies in Marxist Dialectics is a 1923 book by the Hungarian philosopher György Lukács, in which the author re-emphasizes the philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel's influence on the philosopher Karl Marx, analyzes the concept of "class consciousness," and attempts a philosophical justification of Bolshevism.

Various Marxist authors have focused on Marx's method of analysis and presentation as key factors both in understanding the range and incisiveness of Karl Marx's writing in general, his critique of political economy, as well as Grundrisse andDas Kapital in particular. One of the clearest and most instructive examples of this is his discussion of the value-form, which acts as a primary guide or key to understanding the logical argument as it develops throughout the volumes of Das Kapital.

Historical materialism is Karl Marx's theory of history. Marx locates historical change in the rise of class societies and the way humans labor together to make their livelihoods. For Marx and his lifetime collaborator, Friedrich Engels, the ultimate cause and moving power of historical events are to be found in the economic development of society and the social and political upheavals wrought by changes to the mode of production. It provides a challenge to the view that historical processes have come to a close and that capitalism is the end of history. Although Marx never brought together a formal or comprehensive description of historical materialism in one published work, his key ideas are woven into a variety of works from the 1840s onward. Since Marx's time, the theory has been modified and expanded. It now has many Marxist and non-Marxist variants.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to Marxism: