Lipids are a broad group of organic compounds which include fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins, monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The functions of lipids include storing energy, signaling, and acting as structural components of cell membranes. Lipids have applications in the cosmetic and food industries, and in nanotechnology.

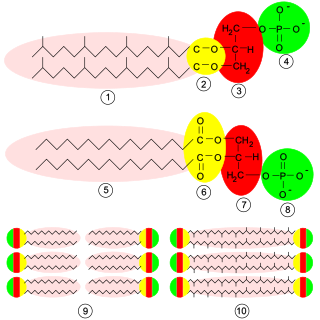

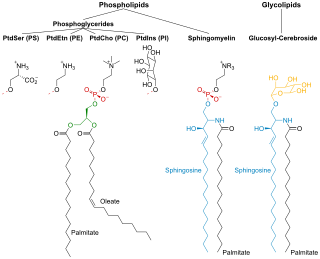

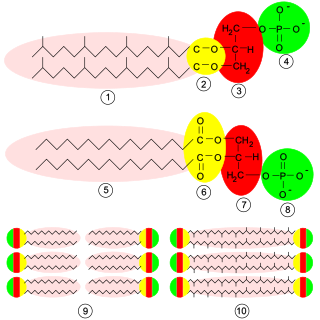

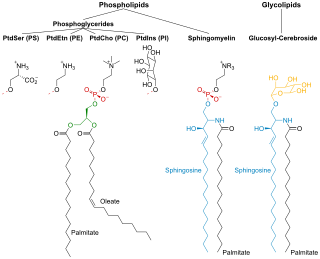

Phospholipids are a class of lipids whose molecule has a hydrophilic "head" containing a phosphate group and two hydrophobic "tails" derived from fatty acids, joined by an alcohol residue. Marine phospholipids typically have omega-3 fatty acids EPA and DHA integrated as part of the phospholipid molecule. The phosphate group can be modified with simple organic molecules such as choline, ethanolamine or serine.

A lipoprotein is a biochemical assembly whose primary function is to transport hydrophobic lipid molecules in water, as in blood plasma or other extracellular fluids. They consist of a triglyceride and cholesterol center, surrounded by a phospholipid outer shell, with the hydrophilic portions oriented outward toward the surrounding water and lipophilic portions oriented inward toward the lipid center. A special kind of protein, called apolipoprotein, is embedded in the outer shell, both stabilising the complex and giving it a functional identity that determines its role.

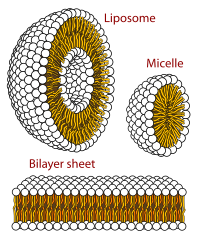

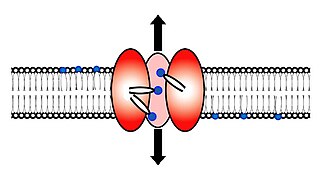

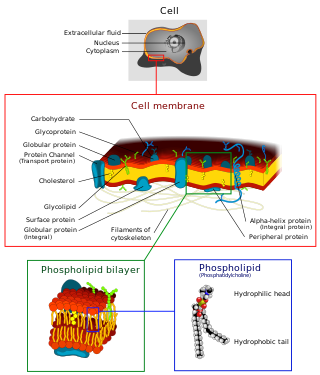

The lipid bilayer is a thin polar membrane made of two layers of lipid molecules. These membranes are flat sheets that form a continuous barrier around all cells. The cell membranes of almost all organisms and many viruses are made of a lipid bilayer, as are the nuclear membrane surrounding the cell nucleus, and membranes of the membrane-bound organelles in the cell. The lipid bilayer is the barrier that keeps ions, proteins and other molecules where they are needed and prevents them from diffusing into areas where they should not be. Lipid bilayers are ideally suited to this role, even though they are only a few nanometers in width, because they are impermeable to most water-soluble (hydrophilic) molecules. Bilayers are particularly impermeable to ions, which allows cells to regulate salt concentrations and pH by transporting ions across their membranes using proteins called ion pumps.

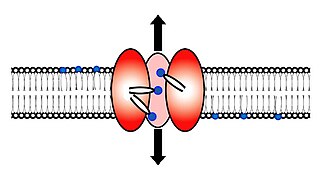

Peripheral membrane proteins, or extrinsic membrane proteins, are membrane proteins that adhere only temporarily to the biological membrane with which they are associated. These proteins attach to integral membrane proteins, or penetrate the peripheral regions of the lipid bilayer. The regulatory protein subunits of many ion channels and transmembrane receptors, for example, may be defined as peripheral membrane proteins. In contrast to integral membrane proteins, peripheral membrane proteins tend to collect in the water-soluble component, or fraction, of all the proteins extracted during a protein purification procedure. Proteins with GPI anchors are an exception to this rule and can have purification properties similar to those of integral membrane proteins.

Semipermeable membrane is a type of biological or synthetic, polymeric membrane that will allow certain molecules or ions to pass through it by osmosis. The rate of passage depends on the pressure, concentration, and temperature of the molecules or solutes on either side, as well as the permeability of the membrane to each solute. Depending on the membrane and the solute, permeability may depend on solute size, solubility, properties, or chemistry. How the membrane is constructed to be selective in its permeability will determine the rate and the permeability. Many natural and synthetic materials which are rather thick are also semipermeable. One example of this is the thin film on the inside of the egg.

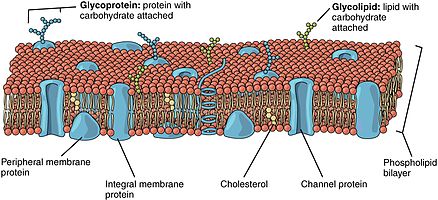

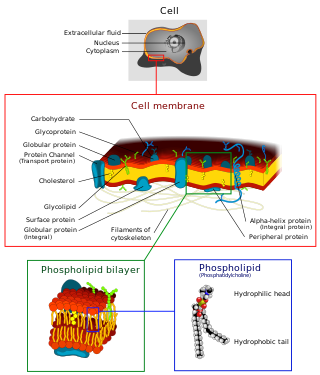

The fluid mosaic model explains various observations regarding the structure of functional cell membranes. According to this biological model, there is a lipid bilayer in which protein molecules are embedded. The phospholipid bilayer gives fluidity and elasticity to the membrane. Small amounts of carbohydrates are also found in the cell membrane. The biological model, which was devised by Seymour Jonathan Singer and Garth L. Nicolson in 1972, describes the cell membrane as a two-dimensional liquid that restricts the lateral diffusion of membrane components. Such domains are defined by the existence of regions within the membrane with special lipid and protein cocoon that promote the formation of lipid rafts or protein and glycoprotein complexes. In addition, it came before the other model that introduced the first bilayer. Another way to define membrane domains is the association of the lipid membrane with the cytoskeleton filaments and the extracellular matrix through membrane proteins. The current model describes important features relevant to many cellular processes, including: cell-cell signaling, apoptosis, cell division, membrane budding, and cell fusion. The fluid mosaic model is the most acceptable model of the plasma membrane. Its main function is to separate the contents of the cell from the exterior.

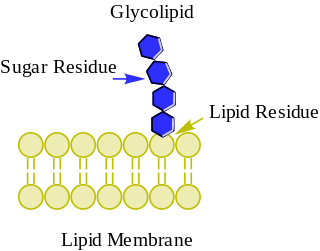

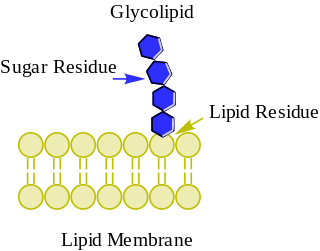

Glycolipids are lipids with a carbohydrate attached by a glycosidic (covalent) bond. Their role is to maintain the stability of the cell membrane and to facilitate cellular recognition, which is crucial to the immune response and in the connections that allow cells to connect to one another to form tissues. Glycolipids are found on the surface of all eukaryotic cell membranes, where they extend from the phospholipid bilayer into the extracellular environment.

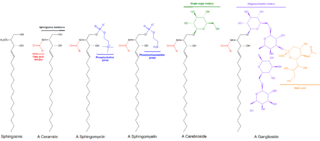

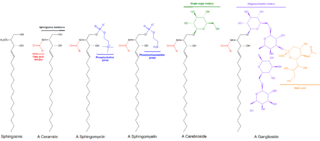

Sphingomyelin is a type of sphingolipid found in animal cell membranes, especially in the membranous myelin sheath that surrounds some nerve cell axons. It usually consists of phosphocholine and ceramide, or a phosphoethanolamine head group; therefore, sphingomyelins can also be classified as sphingophospholipids. In humans, SPH represents ~85% of all sphingolipids, and typically make up 10–20 mol % of plasma membrane lipids.

Glycerophospholipids or phosphoglycerides are glycerol-based phospholipids. They are the main component of biological membranes. Two major classes are known: those for bacteria and eukaryotes and a separate family for archaea.

An amphiphile, or amphipath, is a chemical compound possessing both hydrophilic and lipophilic (fat-loving) properties. Such a compound is called amphiphilic or amphipathic. Amphiphilic compounds include surfactants. The phospholipid amphiphiles are the major structural component of cell membranes.

Scramblase is a protein responsible for the translocation of phospholipids between the two monolayers of a lipid bilayer of a cell membrane. In humans, phospholipid scramblases (PLSCRs) constitute a family of five homologous proteins that are named as hPLSCR1–hPLSCR5. Scramblases are not members of the general family of transmembrane lipid transporters known as flippases. Scramblases are distinct from flippases and floppases. Scramblases, flippases, and floppases are three different types of enzymatic groups of phospholipid transportation enzymes. The inner-leaflet, facing the inside of the cell, contains negatively charged amino-phospholipids and phosphatidylethanolamine. The outer-leaflet, facing the outside environment, contains phosphatidylcholine and sphingomyelin. Scramblase is an enzyme, present in the cell membrane, that can transport (scramble) the negatively charged phospholipids from the inner-leaflet to the outer-leaflet, and vice versa.

Lipid metabolism is the synthesis and degradation of lipids in cells, involving the breakdown and storage of fats for energy and the synthesis of structural and functional lipids, such as those involved in the construction of cell membranes. In animals, these fats are obtained from food and are synthesized by the liver. Lipogenesis is the process of synthesizing these fats. The majority of lipids found in the human body from ingesting food are triglycerides and cholesterol. Other types of lipids found in the body are fatty acids and membrane lipids. Lipid metabolism is often considered as the digestion and absorption process of dietary fat; however, there are two sources of fats that organisms can use to obtain energy: from consumed dietary fats and from stored fat. Vertebrates use both sources of fat to produce energy for organs such as the heart to function. Since lipids are hydrophobic molecules, they need to be solubilized before their metabolism can begin. Lipid metabolism often begins with hydrolysis, which occurs with the help of various enzymes in the digestive system. Lipid metabolism also occurs in plants, though the processes differ in some ways when compared to animals. The second step after the hydrolysis is the absorption of the fatty acids into the epithelial cells of the intestinal wall. In the epithelial cells, fatty acids are packaged and transported to the rest of the body.

Surfactin is a cyclic lipopeptide, commonly used as an antibiotic for its capacity as a surfactant. It is an amphiphile capable of withstanding hydrophilic and hydrophobic environments. The Gram-positive bacterial species Bacillus subtilis produces surfactin for its antibiotic effects against competitors. Surfactin showcases antibacterial, antiviral, antifungal, and hemolytic effects.

In biology, membrane fluidity refers to the viscosity of the lipid bilayer of a cell membrane or a synthetic lipid membrane. Lipid packing can influence the fluidity of the membrane. Viscosity of the membrane can affect the rotation and diffusion of proteins and other bio-molecules within the membrane, there-by affecting the functions of these things.

Membrane lipids are a group of compounds which form the lipid bilayer of the cell membrane. The three major classes of membrane lipids are phospholipids, glycolipids, and cholesterol. Lipids are amphiphilic: they have one end that is soluble in water ('polar') and an ending that is soluble in fat ('nonpolar'). By forming a double layer with the polar ends pointing outwards and the nonpolar ends pointing inwards membrane lipids can form a 'lipid bilayer' which keeps the watery interior of the cell separate from the watery exterior. The arrangements of lipids and various proteins, acting as receptors and channel pores in the membrane, control the entry and exit of other molecules and ions as part of the cell's metabolism. In order to perform physiological functions, membrane proteins are facilitated to rotate and diffuse laterally in two dimensional expanse of lipid bilayer by the presence of a shell of lipids closely attached to protein surface, called annular lipid shell.

One property of a lipid bilayer is the relative mobility (fluidity) of the individual lipid molecules and how this mobility changes with temperature. This response is known as the phase behavior of the bilayer. Broadly, at a given temperature a lipid bilayer can exist in either a liquid or a solid phase. The solid phase is commonly referred to as a “gel” phase. All lipids have a characteristic temperature at which they undergo a transition (melt) from the gel to liquid phase. In both phases the lipid molecules are constrained to the two dimensional plane of the membrane, but in liquid phase bilayers the molecules diffuse freely within this plane. Thus, in a liquid bilayer a given lipid will rapidly exchange locations with its neighbor millions of times a second and will, through the process of a random walk, migrate over long distances.

The cell membrane is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of a cell from the outside environment. The cell membrane consists of a lipid bilayer, made up of two layers of phospholipids with cholesterols interspersed between them, maintaining appropriate membrane fluidity at various temperatures. The membrane also contains membrane proteins, including integral proteins that span the membrane and serve as membrane transporters, and peripheral proteins that loosely attach to the outer (peripheral) side of the cell membrane, acting as enzymes to facilitate interaction with the cell's environment. Glycolipids embedded in the outer lipid layer serve a similar purpose. The cell membrane controls the movement of substances in and out of a cell, being selectively permeable to ions and organic molecules. In addition, cell membranes are involved in a variety of cellular processes such as cell adhesion, ion conductivity, and cell signalling and serve as the attachment surface for several extracellular structures, including the cell wall and the carbohydrate layer called the glycocalyx, as well as the intracellular network of protein fibers called the cytoskeleton. In the field of synthetic biology, cell membranes can be artificially reassembled.

A unilamellar liposome is a spherical liposome, a vesicle, bounded by a single bilayer of an amphiphilic lipid or a mixture of such lipids, containing aqueous solution inside the chamber. Unilamellar liposomes are used to study biological systems and to mimic cell membranes, and are classified into three groups based on their size: small unilamellar liposomes/vesicles (SUVs) that with a size range of 20–100 nm, large unilamellar liposomes/vesicles (LUVs) with a size range of 100–1000 nm and giant unilamellar liposomes/vesicles (GUVs) with a size range of 1-200 µm. GUVs are mostly used as models for biological membranes in research work. Animal cells are 10–30 µm and plant cells are typically 10–100 µm. Even smaller cell organelles such as mitochondria are typically 1-2 µm. Therefore, a proper model should account for the size of the specimen being studied. In addition, the size of vesicles dictates their membrane curvature which is an important factor in studying fusion proteins. SUVs have a higher membrane curvature and vesicles with high membrane curvature can promote membrane fusion faster than vesicles with lower membrane curvature such as GUVs.

Before the emergence of electron microscopy in the 1950s, scientists did not know the structure of a cell membrane or what its components were; biologists and other researchers used indirect evidence to identify membranes before they could actually be visualized. Specifically, it was through the models of Overton, Langmuir, Gorter and Grendel, and Davson and Danielli, that it was deduced that membranes have lipids, proteins, and a bilayer. The advent of the electron microscope, the findings of J. David Robertson, the proposal of Singer and Nicolson, and additional work of Unwin and Henderson all contributed to the development of the modern membrane model. However, understanding of past membrane models elucidates present-day perception of membrane characteristics. Following intense experimental research, the membrane models of the preceding century gave way to the fluid mosaic model that is accepted today.