Cusco, often spelled Cuzco, is a city in Southeastern Peru near the Urubamba Valley of the Andes mountain range. It is the capital of the Cusco Region and of the Cusco Province. The city is the seventh most populous in Peru; in 2017, it had a population of 428,450. Its elevation is around 3,400 m (11,200 ft).

Machu Picchu is a 15th-century Inca citadel located in the Eastern Cordillera of southern Peru on a 2,430-meter (7,970 ft) mountain ridge. Often referred to as the "Lost City of the Incas", it is the most familiar icon of the Inca Empire. It is located in the Machupicchu District within Urubamba Province above the Sacred Valley, which is 80 kilometers (50 mi) northwest of Cusco. The Urubamba River flows past it, cutting through the Cordillera and creating a canyon with a tropical mountain climate.

Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui was the ninth Sapa Inca (1418–1471/1472) of the Kingdom of Cusco which he transformed into the Inca Empire. Most archaeologists now believe that the famous Inca site of Machu Picchu was built as an estate for Pachacuti.

Vilcabamba, Willkapampa is often called the Lost City of the Incas. Vilcabamba means "sacred plain" in Quechua. The modern name for the Inca ruins of Vilcabamba is Espiritu Pampa. Vilcabamba is located in Echarate District of La Convención Province in the Cuzco Region of Peru.

The Chachapoyas, also called the "Warriors of the Clouds", was a culture of the Andes living in the cloud forests of the southern part of the Department of Amazonas of present-day Peru. The Inca Empire conquered their civilization shortly before the Spanish conquest in the 16th century. At the time of the arrival of the conquistadors, the Chachapoyas were one of the many nations ruled by the Incas, although their incorporation had been difficult due to their constant resistance to Inca troops.

Ollantaytambo is a town and an Inca archaeological site in southern Peru some 72 km (45 mi) by road northwest of the city of Cusco. It is located at an altitude of 2,792 m (9,160 ft) above sea level in the district of Ollantaytambo, province of Urubamba, Cusco region. During the Inca Empire, Ollantaytambo was the royal estate of Emperor Pachacuti, who conquered the region, and built the town and a ceremonial center. At the time of the Spanish conquest of Peru, it served as a stronghold for Manco Inca Yupanqui, leader of the Inca resistance. Located in the Sacred Valley of the Incas, it is now an important tourist attraction on account of its Inca ruins and its location en route to one of the most common starting points for the four-day, three-night hike known as the Inca Trail.

The Sacred Valley of the Incas, or the Urubamba Valley, is a valley in the Andes of Peru, north of the Inca capital of Cusco. It is located in the present-day Peruvian region of Cusco. In colonial documents it was referred to as the "Valley of Yucay." The Sacred Valley was incorporated slowly into the incipient Inca Empire during the period from 1000 to 1400 CE.

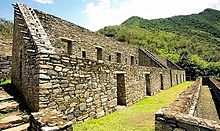

Vitcos was a residence of Inca nobles and a ceremonial center of the Neo-Inca State (1537-1572). The archaeological site of ancient Vitcos, called Rosaspata, is in the Vilcabamba District of La Convención Province, Cusco Region in Peru. The ruins are on a ridge overlooking the junction of two small rivers and the village of Pucyura. The Incas had occupied Vilcabamba, the region in which Vitcos is located, about 1450 CE, establishing major centers at Machu Picchu, Choquequirao, Vitcos, and Vilcabamba. Vitcos was often the residence of the rulers of the Neo-Inca state until the Spanish conquest of this last stronghold of the Incas in 1572.

Llaqtapata (Quechua) llaqta place, pata elevated place / above, at the top / edge, bank, shore, pronounced 'yakta-pahta', Hispanicized Llactapata) is an archaeological site about 5 km (3.1 mi) east of Machu Picchu. The complex is located in the Cusco Region, La Convención Province, Santa Teresa District, high on a ridge between the Ahobamba and Santa Teresa drainages.

The Inca Bridge or Inka Bridge refers to one of two places related to access to Machu Picchu, in Peru.

Peruvian architecture is the architecture carried out during any time in what is now Peru, and by Peruvian architects worldwide. Its diversity and long history spans from ancient Peru, the Inca Empire, Colonial Peru to the present day.

Salcantay, Salkantay or Sallqantay is the highest peak in the Vilcabamba mountain range, part of the Peruvian Andes. It is located in the Cusco Region, about 60 km (40 mi) west-northwest of the city of Cusco. It is the 38th-highest peak in the Andes and the twelfth-highest in Peru. However, as a range highpoint in deeply incised terrain, it is the second most topographically prominent peak in the country, after Huascarán.

A previously unknown Inca settlement, Quriwayrachina or Quri Wayrachina, was found in the Willkapampa mountain range in the Cusco Region of Peru in 2001. The site lies in the Santa Teresa District of the La Convención Province, north of the archaeological site of Choquequirao and west of the mountains Kiswar and Quriwayrachina (Corihuayrachina), on a mountain named Victoria. Close to nearby ancient Inca mines, the surrounding hills are covered with the littered stones from more than 200 structures in this Inca outpost.

Inti Punku or Intipunku is an archaeological site in the Cusco Region of Peru that was once a fortress of the sacred city, Machu Picchu. It is now also the name of the final section of the Incan Trail between the Sun Gate complex and the city of Machu Picchu. It was believed that the steps were a control gate for those who enter and exited the Sanctuary.

Cusichaca River, is a river in Peru located in the Cusco Region, Urubamba Province, on the border of the districts Machupicchu and Ollantaytambo. Its waters flow to the Vilcanota River.

Tipón, is a sprawling early fifteenth-century Inca archaeological park that is situated between 3,250 metres (10,660 ft) and 3,960 metres (12,990 ft) above sea level, located 22 kilometres (14 mi) southeast of Cusco near the village of Tipón. It consists of several ruins enclosed by a powerful defensive wall about 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) long. The most renown part of the park is the group of precise and right angled monumental terraces irrigated by a network of water canals fed by a monumental fountain channeling water from a natural spring. The site includes ancient residential areas and a remarkable amount of petroglyphs in its upper part.

Patallacta, Llactapata or Q'ente Marka is an archaeological site in Peru located in the Cusco Region, Urubamba Province, Machupicchu District. It is situated southeast of the site Machu Picchu, at the confluence of the rivers Cusichaca and Vilcanota on a mountain named Patallacta.

Purunllacta or Purum Llacta (Quechua purum, purun savage, wild / wasteland, llaqta place is an archaeological site of the Chachapoya culture in Peru. It is situated in the Amazonas Region, Chachapoyas Province, Cheto District, on the mountain of the same name. It lies northeast and near the archaeological site of Purunllacta of the Soloco District.

Incahuasi is a mountain in the Vilcabamba mountain range in the Andes of Peru whose summit reaches 4,315 metres (14,157 ft) above sea level. It is situated in the Apurímac Region, Abancay Province, Cachora District. The mountain lies on the bank of the Apurímac River, opposite the archaeological site of Choquequirao. On its northern slope there is a small archaeological site named Inka Raqay. Tourists are also attracted by the viewpoint of Incahuasi which provides good views of the Apurímac valley, Choquequirao and Padreyoc.

The Inca complex at Pisac is a large Incan complex of agricultural terraces, residences, guard posts, watchtowers and a ceremonial/religious centre located along a mountain ridge above the modern town of Pisac in the Sacred Valley of Peru. In 1983 the Pisac National Archeological Park was established to recognize the importance of and to protect the remains of the complex.