Related Research Articles

Musique concrète is a type of music composition that utilizes recorded sounds as raw material. Sounds are often modified through the application of audio signal processing and tape music techniques, and may be assembled into a form of sound collage. It can feature sounds derived from recordings of musical instruments, the human voice, and the natural environment as well as those created using sound synthesis and computer-based digital signal processing. Compositions in this idiom are not restricted to the normal musical rules of melody, harmony, rhythm, and metre. The technique exploits acousmatic sound, such that sound identities can often be intentionally obscured or appear unconnected to their source cause.

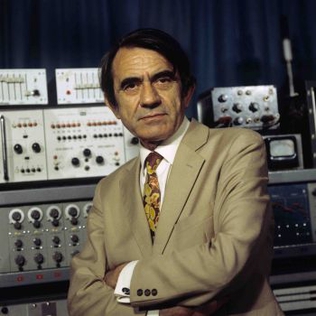

Pierre Henri Marie Schaeffer was a French composer, writer, broadcaster, engineer, musicologist, acoustician and founder of Groupe de Recherche de Musique Concrète (GRMC). His innovative work in both the sciences—particularly communications and acoustics—and the various arts of music, literature and radio presentation after the end of World War II, as well as his anti-nuclear activism and cultural criticism garnered him widespread recognition in his lifetime.

David Eugene Tudor was an American pianist and composer of experimental music.

Aleatoricism or aleatorism, the noun associated with the adjectival aleatory and aleatoric, is a term popularised by the musical composer Pierre Boulez, but also Witold Lutosławski and Franco Evangelisti, for compositions resulting from "actions made by chance", with its etymology deriving from alea, Latin for "dice". It now applies more broadly to art created as a result of such a chance-determined process. The term was first used "in the context of electro-acoustics and information theory" to describe "a course of sound events that is determined in its framework and flexible in detail", by Belgian-German physicist, acoustician, and information theorist Werner Meyer-Eppler. In practical application, in compositions by Mozart and Kirnberger, for instance, the order of the measures of a musical piece were left to be determined by throwing dice, and in performances of music by Pousseur, musicians threw dice "for sheets of music and cues". However, more generally in musical contexts, the term has had varying meanings as it was applied by various composers, and so a single, clear definition for aleatory music is defied. Aleatory should not be confused with either indeterminacy, or improvisation.

20th-century classical music is art music that was written between the years 1901 and 2000, inclusive. Musical style diverged during the 20th century as it never had previously, so this century was without a dominant style. Modernism, impressionism, and post-romanticism can all be traced to the decades before the turn of the 20th century, but can be included because they evolved beyond the musical boundaries of the 19th-century styles that were part of the earlier common practice period. Neoclassicism and expressionism came mostly after 1900. Minimalism started much later in the century and can be seen as a change from the modern to postmodern era, although some date postmodernism from as early as about 1930. Aleatory, atonality, serialism, musique concrète, electronic music, and concept music were all developed during the century. Jazz and ethnic folk music became important influences on many composers during this century.

Contemporary classical music is Western art music composed close to the present day. At the beginning of the 21st century, it commonly referred to the post-1945 modern forms of post-tonal music after the death of Anton Webern, and included serial music, electronic music, experimental music, and minimalist music. Newer forms of music include spectral music, and post-minimalism.

In music, montage or sound collage is a technique where newly branded sound objects or compositions, including songs, are created from collage, also known as montage. This is often done through the use of sampling, while some playable sound collages were produced by gluing together sectors of different vinyl records. In any case, it may be achieved through the use of previous sound recordings or musical scores. Like its visual cousin, the collage work may have a completely different effect than that of the component parts, even if the original parts are completely recognizable or from only one source.

Electroacoustic music is a genre of popular and Western art music in which composers use technology to manipulate the timbres of acoustic sounds, sometimes by using audio signal processing, such as reverb or harmonizing, on acoustical instruments. It originated around the middle of the 20th century, following the incorporation of electric sound production into compositional practice. The initial developments in electroacoustic music composition to fixed media during the 20th century are associated with the activities of the Groupe de recherches musicales at the ORTF in Paris, the home of musique concrète, the Studio for Electronic Music in Cologne, where the focus was on the composition of elektronische Musik, and the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center in New York City, where tape music, electronic music, and computer music were all explored. Practical electronic music instruments began to appear in the early 20th century.

In music, modernism is an aesthetic stance underlying the period of change and development in musical language that occurred around the turn of the 20th century, a period of diverse reactions in challenging and reinterpreting older categories of music, innovations that led to new ways of organizing and approaching harmonic, melodic, sonic, and rhythmic aspects of music, and changes in aesthetic worldviews in close relation to the larger identifiable period of modernism in the arts of the time. The operative word most associated with it is "innovation". Its leading feature is a "linguistic plurality", which is to say that no one music genre ever assumed a dominant position.

Inherent within musical modernism is the conviction that music is not a static phenomenon defined by timeless truths and classical principles, but rather something which is intrinsically historical and developmental. While belief in musical progress or in the principle of innovation is not new or unique to modernism, such values are particularly important within modernist aesthetic stances.

Acousmatic music is a form of electroacoustic music that is specifically composed for presentation using speakers, as opposed to a live performance. It stems from a compositional tradition that dates back to the origins of musique concrète in the late 1940s. Unlike acoustic or electroacoustic musical works that are realized from scores, compositions that are purely acousmatic often exist solely as fixed media audio recordings.

Surrealist music is music which uses unexpected juxtapositions and other surrealist techniques. Discussing Theodor W. Adorno, Max Paddison defines surrealist music as that which "juxtaposes its historically devalued fragments in a montage-like manner which enables them to yield up new meanings within a new aesthetic unity", though Lloyd Whitesell says this is Paddison's gloss of the term. Anne LeBaron cites automatism, including improvisation, and collage as the primary techniques of musical surrealism. According to Whitesell, Paddison quotes Adorno's 1930 essay "Reaktion und Fortschritt" as saying "Insofar as surrealist composing makes use of devalued means, it uses these as devalued means, and wins its form from the 'scandal' produced when the dead suddenly spring up among the living."

Darmstadt School refers to a group of composers who were associated with the Darmstadt International Summer Courses for New Music from the early 1950s to the early 1960s in Darmstadt, Germany, and who shared some aesthetic attitudes. Initially, this included only Pierre Boulez, Bruno Maderna, Luigi Nono, and Karlheinz Stockhausen, but others came to be added, in various ways. The term does not refer to an educational institution.

Structures I (1952) and Structures II (1961) are two related works for two pianos, composed by the French composer Pierre Boulez.

Punctualism is a style of musical composition prevalent in Europe between 1949 and 1955 "whose structures are predominantly effected from tone to tone, without superordinate formal conceptions coming to bear". In simpler terms: "music that consists of separately formed particles—however complexly these may be composed—[is called] punctual music, as opposed to linear, or group-formed, or mass-formed music", bolding in the source). This was accomplished by assigning to each note in a composition values drawn from scales of pitch, duration, dynamics, and attack characteristics, resulting in a "stronger individualizing of separate tones". Another important factor was maintaining discrete values in all parameters of the music. Punctual dynamics, for example

mean that all dynamic degrees are fixed; one point will be linked directly to another on the chosen scale, without any intervening transition or gesture. Line-dynamics, on the other hand, involve the transitions from one given amplitude to another: crescendo, decrescendo and their combinations. This second category can be defined as a dynamic glissando, comparable to glissandi of pitch and of tempi.

Indeterminacy is a composing approach in which some aspects of a musical work are left open to chance or to the interpreter's free choice. John Cage, a pioneer of indeterminacy, defined it as "the ability of a piece to be performed in substantially different ways".

Live electronic music is a form of music that can include traditional electronic sound-generating devices, modified electric musical instruments, hacked sound generating technologies, and computers. Initially the practice developed in reaction to sound-based composition for fixed media such as musique concrète, electronic music and early computer music. Musical improvisation often plays a large role in the performance of this music. The timbres of various sounds may be transformed extensively using devices such as amplifiers, filters, ring modulators and other forms of circuitry. Real-time generation and manipulation of audio using live coding is now commonplace.

The Konkrete Etüde is the earliest work of electroacoustic tape music by Karlheinz Stockhausen, composed in 1952 and lasting just three-and-a-quarter minutes. The composer retrospectively gave it the number "1⁄5" in his catalogue of works.

French electronic music is a panorama of French music that employs electronic musical instruments and electronic music technology in its production.

References

- 1 2 Anon. n.d.

- ↑ Sun 2013.

- ↑ Palombini 1993a, 18.

- ↑ Schaeffer 1957.

- ↑ Palombini 1993a, 19.

- ↑ Palombini 1993b, 557.

- ↑ Cage 1961, 39.

- ↑ Mauceri 1997, 197.

- 1 2 Rebner 1997.

- ↑ Nyman 1974, 1.

- ↑ Nyman 1974, 78–81, 93–115.

- ↑ Nyman 1974, 2, 9.

- ↑ Cage 1961, 13.

- ↑ Cope 1997, 222.

- ↑ Nicholls 1998, 318.

- ↑ Burt 1991, 5.

- ↑ Piekut 2008, 2–5.

- ↑ Piekut 2008, 5.

- ↑ Piekut 2008, 7.

- ↑ Meyer 1994, 106–107, 266.

- ↑ Meyer 1994, 237.

- ↑ Metzger 1959, 21.

- ↑ Mauceri 1997, 189.

- ↑ Boulez 1986, 430, 431.

- ↑ Mauceri 1997, 190.

- ↑ Nyman 1974, 5.

- ↑ Nyman 1974, 9.

- ↑ Hiller and Isaacson 1959.

- ↑ Vignal 2003, 298.

- ↑ Nicholls 1990.

- ↑ Bateman n.d.

- ↑ Blake 1999.

- ↑ Jaffe 1983.

- ↑ Lubet 1999.

Sources

- Anon. n.d. "Avant-Garde » Modern Composition » Experimental". AllMusic

- Bateman, Shahbeila. n.d. "Biography of Yoko Ono". Website of Hugh McCarney, Communication Department, Western Connecticut University. (Accessed 15 February 2009)

- Blake, Michael. 1999. "The Emergence of a South African Experimental Aesthetic". In Proceedings of the 25th Annual Congress of the Musicological Society of Southern Africa, edited by Izak J. Grové. Pretoria: Musicological Society of Southern Africa.

- Boulez, Pierre. 1986. "Experiment, Ostriches, and Music", in his Orientations: Collected Writings, translated by Martin Cooper, 430–431. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-64375-5 Originally published as "Expérience, autriches et musique". La Nouvelle Revue française , no. 36 (December 1955): 1, 174–176.

- Burt, Warren. 1991. "Australian Experimental Music 1963–1990". Leonardo Music Journal 1, no. 1:5–10.

- Cage, John. 1961. Silence: Lectures and Writings. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press. Unaltered reprints: Wesleyan University press, 1966 (pbk), 1967 (cloth), 1973 (pbk ["First Wesleyan paperback edition"], 1975 (unknown binding); Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1966, 1967, 1969, 1970, 1971; London: Calder & Boyars, 1968, 1971, 1973 ISBN 0-7145-0526-9 (cloth) ISBN 0-7145-1043-2 (pbk). London: Marion Boyars, 1986, 1999 ISBN 0-7145-1043-2 (pbk); [n.p.]: Reprint Services Corporation, 1988 (cloth) ISBN 99911-780-1-5 [In particular the essays "Experimental Music", pp. 7–12, and "Experimental Music: Doctrine", pp. 13–17.]

- Cope, David. 1997. Techniques of the Contemporary Composer. New York: Schirmer Books. ISBN 0-02-864737-8.

- Hiller, Lejaren, and L. M. Isaacson. 1959. Experimental Music: Composition with an Electronic Computer. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Jaffe, Lee David. 1983. "The Last Days of the Avant Garde; or How to Tell Your Glass from Your Eno". Drexel Library Quarterly 19, no. 1 (Winter): 105–122.

- Lubet, Alex. 1999. "Indeterminate Origins: A Cultural theory of American Experimental Music". In Perspectives on American music since 1950, edited by James R. Heintze. New York: General Music Publishing Co. ISBN 0-8153-2144-9

- Mauceri, Frank X. 1997. "From Experimental Music to Musical Experiment". Perspectives of New Music 35, no. 1 (Winter): 187-204.

- Metzger, Heinz-Klaus. 1959. "Abortive Concepts in the Theory and Criticism of Music", translated by Leo Black. Die Reihe 5: "Reports, Analysis" (English edition): 21–29).

- Meyer, Leonard B. 1994. Music, the Arts, and Ideas: Patterns and Predictions in Twentieth-Century Culture. Second edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-52143-5.

- Nicholls, David. 1990. American Experimental Music, 1890–1940. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-34578-2.

- Nicholls, David. 1998. "Avant-garde and Experimental Music". In Cambridge History of American Music. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-45429-8.

- Nyman, Michael. 1974. Experimental Music: Cage and Beyond. London: Studio Vista ISBN 0-289-70182-1. New York: Schirmer Books. ISBN 0-02-871200-5. Second edition, Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-521-65297-9.

- Palombini, Carlos. 1993a. "Machine Songs V: Pierre Schaeffer: From Research into Noises to Experimental Music". Computer Music Journal , 17, No. 3 (Autumn): 14–19.

- Palombini, Carlos. 1993b. "Pierre Schaeffer, 1953: Towards an Experimental Music". Music & Letters 74, no. 4 (November): 542–557.

- Piekut, Benjamin. 2008. "Testing, Testing ...: New York Experimentalism 1964". Ph.D. diss. New York: Columbia University.

- Rebner, Wolfgang Edward. 1997. "Amerikanische Experimentalmusik". In Im Zenit der Moderne: Geschichte und Dokumentation in vier Bänden—Die Internationalen Ferienkurse für Neue Musik Darmstadt, 1946–1966. Rombach Wissenschaften: Reihe Musicae 2, 4 vols., edited by Gianmario Borio and Hermann Danuser, 3:178–189. Freiburg im Breisgau: Rombach.

- Schaeffer, Pierre. 1957. "Vers une musique experimentale". La Revue musicale no. 236 (Vers une musique experimentale), edited by Pierre Schaeffer, 18–23. Paris: Richard-Masse.

- Sun, Cecilia. 2013. "Experimental Music". 2013. The Grove Dictionary of American Music, second edition, edited by Charles Hiroshi Garrett. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Vignal, Marc (ed.). 2003. "Expérimentale (musique)". In Dictionnaire de la musique. Paris: Larousse. ISBN 2-03-511354-7.