A definition of music endeavors to give an accurate and concise explanation of music's basic attributes or essential nature and it involves a process of defining what is meant by the term music. Many authorities have suggested definitions, but defining music turns out to be more difficult than might first be imagined, and there is ongoing debate. A number of explanations start with the notion of music as organized sound, but they also highlight that this is perhaps too broad a definition and cite examples of organized sound that are not defined as music, such as human speech and sounds found in both natural and industrial environments. The problem of defining music is further complicated by the influence of culture in music cognition.

Modernism is a movement that attempts a radical break with previous ideas in art, literature, philosophy, culture, and social organization. It emerged during the late 19th and early 20th centuries in response to significant changes in Western culture, including secularization and the growing importance of science. The movement was influenced by widespread technological innovation, industrialization, and urbanization, as well as the particular cultural and geopolitical shifts that occurred after World War 1. Artistic movements and techniques associated with modernism include abstract art, stream of consciousness in literature, cinematic montage, atonal and twelve-tone music, and modern architecture.

Postmodern music is music in the art music tradition produced in the postmodern era. It also describes any music that follows aesthetical and philosophical trends of postmodernism. As an aesthetic movement it was formed partly in reaction to modernism but is not primarily defined as oppositional to modernist music. Postmodernists question the tight definitions and categories of academic disciplines, which they regard simply as the remnants of modernity.

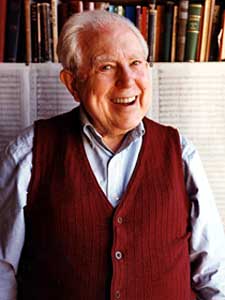

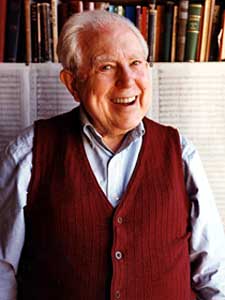

Elliott Cook Carter Jr. was an American modernist composer. One of the most respected composers of the second half of the 20th century, he combined elements of European modernism and American "ultra-modernism" into a distinctive style with a personal harmonic and rhythmic language, after an early neoclassical phase. His compositions are performed throughout the world, and include orchestral, chamber music, solo instrumental, and vocal works. The recipient of many awards, Carter was twice awarded the Pulitzer Prize for his string quartets; he also wrote the large-scale orchestral triptych Symphonia: sum fluxae pretium spei.

Avant-garde music is music that is considered to be at the forefront of innovation in its field, with the term "avant-garde" implying a critique of existing aesthetic conventions, rejection of the status quo in favor of unique or original elements, and the idea of deliberately challenging or alienating audiences. Avant-garde music may be distinguished from experimental music by the way it adopts an extreme position within a certain tradition, whereas experimental music lies outside tradition.

20th-century classical music is art music that was written between the years 1901 and 2000, inclusive. Musical style diverged during the 20th century as it never had previously, so this century was without a dominant style. Modernism, impressionism, and post-romanticism can all be traced to the decades before the turn of the 20th century, but can be included because they evolved beyond the musical boundaries of the 19th-century styles that were part of the earlier common practice period. Neoclassicism and expressionism came mostly after 1900. Minimalism started much later in the century and can be seen as a change from the modern to postmodern era, although some date postmodernism from as early as about 1930. Aleatory, atonality, serialism, musique concrète, electronic music, and concept music were all developed during the century. Jazz and ethnic folk music became important influences on many composers during this century.

Contemporary classical music is Western art music composed close to the present day. At the beginning of the 21st century, it commonly referred to the post-1945 modern forms of post-tonal music after the death of Anton Webern, and included serial music, electronic music, experimental music, and minimalist music. Newer forms of music include spectral music, and post-minimalism.

In music, modernism is an aesthetic stance underlying the period of change and development in musical language that occurred around the turn of the 20th century, a period of diverse reactions in challenging and reinterpreting older categories of music, innovations that led to new ways of organizing and approaching harmonic, melodic, sonic, and rhythmic aspects of music, and changes in aesthetic worldviews in close relation to the larger identifiable period of modernism in the arts of the time. The operative word most associated with it is "innovation". Its leading feature is a "linguistic plurality", which is to say that no one music genre ever assumed a dominant position.

Inherent within musical modernism is the conviction that music is not a static phenomenon defined by timeless truths and classical principles, but rather something which is intrinsically historical and developmental. While belief in musical progress or in the principle of innovation is not new or unique to modernism, such values are particularly important within modernist aesthetic stances.

Neoclassicism in music was a twentieth-century trend, particularly current in the interwar period, in which composers sought to return to aesthetic precepts associated with the broadly defined concept of "classicism", namely order, balance, clarity, economy, and emotional restraint. As such, neoclassicism was a reaction against the unrestrained emotionalism and perceived formlessness of late Romanticism, as well as a "call to order" after the experimental ferment of the first two decades of the twentieth century. The neoclassical impulse found its expression in such features as the use of pared-down performing forces, an emphasis on rhythm and on contrapuntal texture, an updated or expanded tonal harmony, and a concentration on absolute music as opposed to Romantic program music.

Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima, also translated as Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima, is a musical composition for 52 string instruments composed in 1961 by Krzysztof Penderecki. Dedicated to the residents of Hiroshima killed and injured by the first-ever wartime usage of an atomic weapon, the composition won the Tribune Internationale des Compositeurs UNESCO prize that same year.

"Cognitive Constraints on Compositional Systems" is an essay by Fred Lerdahl that cites Pierre Boulez's Le Marteau sans maître (1955) as an example of "a huge gap between compositional system and cognized result," though he "could have illustrated just as well with works by Milton Babbitt, Elliott Carter, Luigi Nono, Karlheinz Stockhausen, or Iannis Xenakis". To explain this gap, and in hopes of bridging it, Lerdahl proposes the concept of a musical grammar, "a limited set of rules that can generate indefinitely large sets of musical events and/or their structural descriptions". He divides this further into compositional grammar and listening grammar, the latter being one "more or less unconsciously employed by auditors, that generates mental representations of the music". He divides the former into natural and artificial compositional grammars. While the two have historically been fruitfully mixed, a natural grammar arises spontaneously in a culture while an artificial one is a conscious invention of an individual or group in a culture; the gap can arise only between listening grammar and artificial grammars. To begin to understand the listening grammar, Lerdahl and Ray Jackendoff created a theory of musical cognition, A Generative Theory of Tonal Music. That theory is outlined in the essay.

Music semiology (semiotics) is the study of signs as they pertain to music on a variety of levels.

Acousmatic music is a form of electroacoustic music that is specifically composed for presentation using speakers, as opposed to a live performance. It stems from a compositional tradition that dates back to the origins of musique concrète in the late 1940s. Unlike acoustic or electroacoustic musical works that are realized from scores, compositions that are purely acousmatic often exist solely as fixed media audio recordings.

Surrealist music is music which uses unexpected juxtapositions and other surrealist techniques. Discussing Theodor W. Adorno, Max Paddison defines surrealist music as that which "juxtaposes its historically devalued fragments in a montage-like manner which enables them to yield up new meanings within a new aesthetic unity", though Lloyd Whitesell says this is Paddison's gloss of the term. Anne LeBaron cites automatism, including improvisation, and collage as the primary techniques of musical surrealism. According to Whitesell, Paddison quotes Adorno's 1930 essay "Reaktion und Fortschritt" as saying "Insofar as surrealist composing makes use of devalued means, it uses these as devalued means, and wins its form from the 'scandal' produced when the dead suddenly spring up among the living."

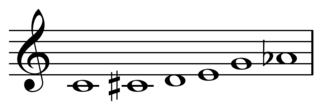

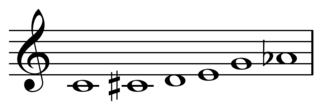

An all-interval tetrachord is a tetrachord, a collection of four pitch classes, containing all six interval classes. There are only two possible all-interval tetrachords, when expressed in prime form. In set theory notation, these are [0,1,4,6] (4-Z15) and [0,1,3,7] (4-Z29). Their inversions are [0,2,5,6] (4-Z15b) and [0,4,6,7] (4-Z29b). The interval vector for all all-interval tetrachords is [1,1,1,1,1,1].

In music, neoconservative postmodernism is "a sort of 'postmodernism of reaction'," which values "textual unity and organicism as totalizing musical structures" like "latter-day modernists".

Neoconservative modernism...critically engages modernism, but rejects it out of hand. Neoconservative composers employ premodern styles in an attempt to bring a new type of coherence to the 'heterogeneous present' and re-establish the dominance of Western musical practice. Jann Pasler notes the musical characteristics that are indicative of a neoconservative postmodernism: "In music, we all know about the nostalgia that has gripped composers in recent years, resulting in neo-romantic works ... the sudden popularity of writing operas and symphonies again, of construing one's ideas in tonal terms. ...Many of those returning to romantic sentiment, narrative curve, or simple melody wish to entice audiences back to the concert hall. To the extent that these developments are a true "about face," they represent a postmodernism of reaction, a return to pre-modernist musical thinking [emphasis added].

In music, the all-trichord hexachord is a unique hexachord that contains all twelve trichords, or from which all twelve possible trichords may be derived. The prime form of this set class is {012478} and its Forte number is 6-Z17. Its complement is 6-Z43 and they share the interval vector of <3,2,2,3,3,2>.

In music, an all-interval twelve-tone row, series, or chord, is a twelve-tone tone row arranged so that it contains one instance of each interval within the octave, 1 through 11. A "twelve-note spatial set made up of the eleven intervals [between consecutive pitches]." There are 1,928 distinct all-interval twelve-tone rows. These sets may be ordered in time or in register. "Distinct" in this context means in transpositionally and rotationally normal form, and disregarding inversionally related forms. These 1,928 tone rows have been independently rediscovered several times, their first computation probably was by Andre Riotte in 1961.