Related Research Articles

Musique concrète is a type of music composition that utilizes recorded sounds as raw material. Sounds are often modified through the application of audio signal processing and tape music techniques, and may be assembled into a form of sound collage. It can feature sounds derived from recordings of musical instruments, the human voice, and the natural environment as well as those created using sound synthesis and computer-based digital signal processing. Compositions in this idiom are not restricted to the normal musical rules of melody, harmony, rhythm, and metre. The technique exploits acousmatic sound, such that sound identities can often be intentionally obscured or appear unconnected to their source cause.

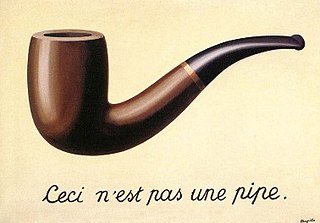

Surrealism is an art and cultural movement that developed in Europe in the aftermath of World War I in which artists aimed to allow the unconscious mind to express itself, often resulting in the depiction of illogical or dreamlike scenes and ideas. Its intention was, according to leader André Breton, to "resolve the previously contradictory conditions of dream and reality into an absolute reality, a super-reality", or surreality. It produced works of painting, writing, theatre, filmmaking, photography, and other media as well.

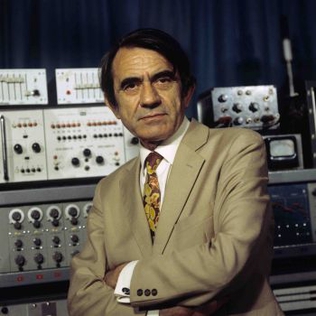

Pierre Henri Marie Schaeffer was a French composer, writer, broadcaster, engineer, musicologist, acoustician and founder of Groupe de Recherche de Musique Concrète (GRMC). His innovative work in both the sciences—particularly communications and acoustics—and the various arts of music, literature and radio presentation after the end of World War II, as well as his anti-nuclear activism and cultural criticism garnered him widespread recognition in his lifetime.

Luc Ferrari was a French composer of Italian heritage and a pioneer in musique concrète and electroacoustic music. He was a founding member of RTF's Groupe de Recherches Musicales (GRMC), working alongside composers such as Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry.

In music, montage or sound collage is a technique where newly branded sound objects or compositions, including songs, are created from collage, also known as Musique concrète. This is often done through the use of sampling, while some sound collages are produced by gluing together sectors of different vinyl records. Like its visual cousin, sound collage works may have a completely different effect than that of the component parts, even if the original parts are recognizable or from a single source. Audio collage was a feature of the audio art of John Cage, Fluxus, postmodern hip-hop and postconceptual digital art.

Michel Chion is a French film theorist and composer of experimental music.

François Bayle is a composer of Electronic Music, Musique concrète. He coined the term Acousmatic Music.

Experimental music is a general label for any music or music genre that pushes existing boundaries and genre definitions. Experimental compositional practice is defined broadly by exploratory sensibilities radically opposed to, and questioning of, institutionalized compositional, performing, and aesthetic conventions in music. Elements of experimental music include indeterminacy, in which the composer introduces the elements of chance or unpredictability with regard to either the composition or its performance. Artists may approach a hybrid of disparate styles or incorporate unorthodox and unique elements.

Guy Reibel is a French contemporary classical music composer.

The bibliography of Pierre Schaeffer is a list of the fictional and nonfictional writings of the electroacoustic musician-theoretician and pioneer of musique concrète, Pierre Schaeffer.

Christian Zanési is a French composer.

André Almuró was a French radio producer, composer, and film director.

Symphonie pour un homme seul is a musical composition by Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry, composed in 1949–1950. It is an important early example of musique concrète.

Musique(s) électronique(s): les bruitistes et leur descendance is a documentary film shot between 2010 and 2012 by filmmaker Jérémie Carboni.

Daniel Paul Charles was a French musician, musicologist and philosopher. He was born on 27 November 1935 in Oran (Algeria) and died on 21 August 2008 in Antibes (France).

The Studio d'Essai, later Club d'Essai, was founded in 1942 by Pierre Schaeffer, played a role in the activities of the French resistance during World War II, and later became a center of musical activity.

French electronic music is a panorama of French music that employs electronic musical instruments and electronic music technology in its production.

Marcel Frémiot was a French composer and musicologist.

Makis Solomos was a Franco-Greek musicologist who specialized in contemporary music and particularly in the work of Iannis Xenakis. He is also one of the specialists of Adorno's thought. His work focuses on the issue of sound ecology and decay. He has published articles and books and participates in meetings and symposia. In 2005, he also participated in the creation of the magazine "Filigranes" which aims to broaden the field of musicology.

Valérie SoudèresnéeBriggs, also known in her early days as Valerie Hamilton, was a French pianist, composer, and pedagogue.

References

- ↑ Paddison 1993, 90.

- ↑ Whitesell 2004, 118.

- ↑ LeBaron 2002, 27.

- ↑ Whitesell 2004, 107, 118n18.

- ↑ LeBaron 2002, 30.

- ↑ Calkins 2010, 13.

- ↑ LeBaron 2002, 30–31.

- ↑ Lewis 2018, 7.

- ↑ Adorno 2002, 396.

- ↑ Adorno 2002, 396–397.

- ↑ Palombini 1993, p. 6.

- ↑ Messiaen 1959, 5–6.

- ↑ Schaeffer 1952, 30–33.

- ↑ Schaeffer 1957, 19–20.

Sources

- Adorno, Theodor W. (2002). Essays on Music, selected, with introduction, commentary, and notes by Richard Leppert; new translations by Susan H. Gillespie. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22672-0 (cloth), ISBN 0-520-23159-7 (pbk).

- Calkins, Susan (2010). "Modernism in Music and Erik Satie's Parade". International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music 41, no. 1 (June): 3–19.

- Lebaron, Anne (2002). "Reflections of Surrealism in Postmodern Musics", Postmodern Music/Postmodern Thought, edited by Judy Lochhead and Joseph Auner, [ page needed ]. Studies in Contemporary Music and Culture 4. New York and London: Garland. ISBN 0-8153-3820-1.

- Lewis, Hannah (18 October 2018). "Surrealist Sounds". French Musical Culture and the Coming of Sound Cinema. New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780190635978.003.0003. ISBN 9780190635978. OCLC 1101181263.

- Messiaen, Olivier (1959). "Préface". La Revue musicale , no. 244 (Experiences musicales: musiques concrète, electronique, exotique, par le Groupe de recherches musicales de la Radiodiffusion Télévision française) : 5-6.

- Paddison, Max (1993), Adorno's Aesthetics of Music, Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-43321-5

- Palombini, Carlos Vincente de Lima (1993). Pierre Schaeffers typo-morphology of sonic objects (doctoral thesis). Durham University. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- Schaeffer, Pierre (1952), A la recherche d'une musique concrète, Paris: Éditions du Seuil

- Schaeffer, Pierre (1957). Schaeffer, Pierre (ed.). "Vers une musique expérimentale." La Revue musicale, no. 236.

- Whitesell, Lloyd (2004). "Twentieth-Century Tonality, or, Breaking Up Is Hard to Do". In The Pleasure of Modernist Music: Listening, Meaning, Intention, Ideology, edited by Arved Mark Ashby. Rochester, New York: University of Rochester Press. ISBN 1-58046-143-3.