Political ecology is the study of the relationships between political, economic and social factors with environmental issues and changes. Political ecology differs from apolitical ecological studies by politicizing environmental issues and phenomena.

Feminist theory is the extension of feminism into theoretical, fictional, or philosophical discourse. It aims to understand the nature of gender inequality. It examines women's and men's social roles, experiences, interests, chores, and feminist politics in a variety of fields, such as anthropology and sociology, communication, media studies, psychoanalysis, political theory, home economics, literature, education, and philosophy.

Socialist feminism rose in the 1960s and 1970s as an offshoot of the feminist movement and New Left that focuses upon the interconnectivity of the patriarchy and capitalism. However, the ways in which women's private, domestic, and public roles in society has been conceptualized, or thought about, can be traced back to Mary Wollstonecraft's A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) and William Thompson's utopian socialist work in the 1800s. Ideas about overcoming the patriarchy by coming together in female groups to talk about personal problems stem from Carol Hanisch. This was done in an essay in 1969 which later coined the term 'the personal is political.' This was also the time that second wave feminism started to surface which is really when socialist feminism kicked off. Socialist feminists argue that liberation can only be achieved by working to end both the economic and cultural sources of women's oppression.

Charlene Spretnak is an American author who has written nine books on cultural history, social criticism, religion and spirituality, and art.

Val Plumwood was an Australian philosopher and ecofeminist known for her work on anthropocentrism. From the 1970s she played a central role in the development of radical ecosophy. Working mostly as an independent scholar, she held positions at the University of Tasmania, North Carolina State University, the University of Montana, and the University of Sydney, and at the time of her death was Australian Research Council Fellow at the Australian National University. She is included in Routledge's Fifty Key Thinkers on the Environment (2001).

Ecospirituality connects the science of ecology with spirituality. It brings together religion and environmental activism. Ecospirituality has been defined as "a manifestation of the spiritual connection between human beings and the environment." The new millennium and the modern ecological crisis has created a need for environmentally based religion and spirituality. Ecospirituality is understood by some practitioners and scholars as one result of people wanting to free themselves from a consumeristic and materialistic society. Ecospirituality has been critiqued for being an umbrella term for concepts such as deep ecology, ecofeminism, and nature religion.

In the early 1960s, an interest in women and their connection with the environment was sparked, largely by a book written by Esther Boserup entitled Woman's Role in Economic Development. Starting in the 1980s, policy makers and governments became more mindful of the connection between the environment and gender issues. Changes began to be made regarding natural resource and environmental management with the specific role of women in mind. According to the World Bank in 1991, "Women play an essential role in the management of natural resources, including soil, water, forests and energy...and often have a profound traditional and contemporary knowledge of the natural world around them". Whereas women were previously neglected or ignored, there was increasing attention paid to the impact of women on the natural environment and, in return, the effects the environment has on the health and well-being of women. The gender-environment relations have valuable ramifications in regard to the understanding of nature between men and women, the management and distribution of resources and responsibilities, and the day-to-day life and well-being of people.

Ariel Salleh is an Australian sociologist who writes on humanity-nature relations, political ecology, social change movements, and ecofeminism.

Greta Gaard is an ecofeminist writer, scholar, activist, and documentary filmmaker. Gaard's academic work in the realms of ecocriticism and ecocomposition is widely cited by scholars in the disciplines of composition and literary criticism. Her theoretical work extending ecofeminist thought into queer theory, queer ecology, vegetarianism, and animal liberation has been influential within women's studies. A cofounder of the Minnesota Green Party, Gaard documented the transition of the U.S. Green movement into the Green Party of the United States in her book, Ecological Politics. She is currently a professor of English at University of Wisconsin-River Falls and a community faculty member in Women's Studies at Metropolitan State University, Twin Cities.

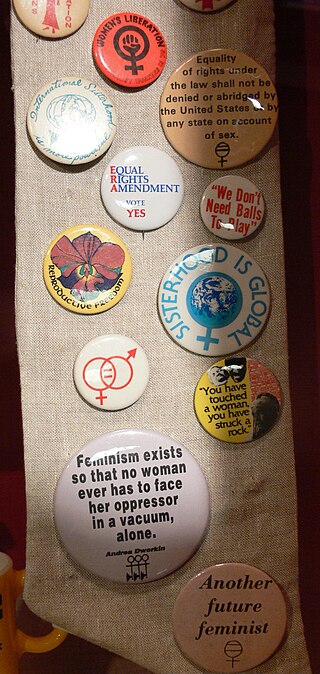

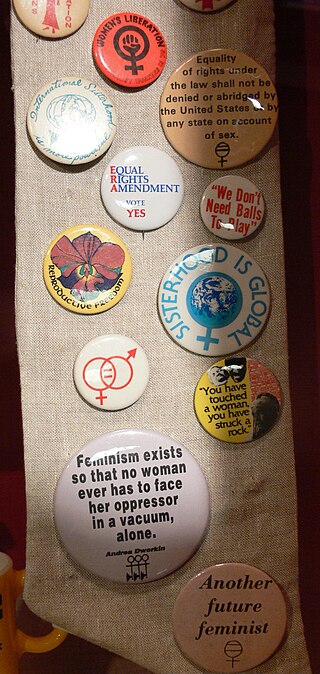

A variety of movements of feminist ideology have developed over the years. They vary in goals, strategies, and affiliations. They often overlap, and some feminists identify themselves with several branches of feminist thought.

Feminist political theory is an area of philosophy that focuses on understanding and critiquing the way political philosophy is usually construed and on articulating how political theory might be reconstructed in a way that advances feminist concerns. Feminist political theory combines aspects of both feminist theory and political theory in order to take a feminist approach to traditional questions within political philosophy.

Feminist ethics is an approach to ethics that builds on the belief that traditionally ethical theorizing has undervalued and/or underappreciated women's moral experience, which is largely male-dominated, and it therefore chooses to reimagine ethics through a holistic feminist approach to transform it.

Buddhist feminism is a movement that seeks to improve the religious, legal, and social status of women within Buddhism. It is an aspect of feminist theology which seeks to advance and understand the equality of men and women morally, socially, spiritually, and in leadership from a Buddhist perspective. The Buddhist feminist Rita Gross describes Buddhist feminism as "the radical practice of the co-humanity of women and men."

Chris Cuomo is the Professor of Philosophy and Women's Studies at the University of Georgia. She is also an affiliate faculty member of the Environmental Ethics Certificate Program, the Institute for African-American Studies, and the Institute for Native American Studies Before moving to the University of Georgia, Cuomo was the Obed J. Wilson Professor of Ethics at the University of Cincinnati.

Ecofeminism is a branch of feminism and political ecology. Ecofeminist thinkers draw on the concept of gender to analyse the relationships between humans and the natural world. The term was coined by the French writer Françoise d'Eaubonne in her book Le Féminisme ou la Mort (1974). Ecofeminist theory asserts a feminist perspective of Green politics that calls for an egalitarian, collaborative society in which there is no one dominant group. Today, there are several branches of ecofeminism, with varying approaches and analyses, including liberal ecofeminism, spiritual/cultural ecofeminism, and social/socialist ecofeminism. Interpretations of ecofeminism and how it might be applied to social thought include ecofeminist art, social justice and political philosophy, religion, contemporary feminism, and poetry.

Ecofeminist art emerged in the 1970s in response to ecofeminist philosophy, that was particularly articulated by writers such as Carolyn Merchant, Val Plumwood, Donna Haraway, Starhawk, Greta Gaard, Karen J. Warren, and Rebecca Solnit. Those writers emphasized the significance of relationships of cultural dominance and ethics expressed as sexism (Haraway), spirituality (Starhawk), speciesism, capitalist values that privilege objectification and the importance of vegetarianism in these contexts (Gaard). The main issues Ecofeminism aims to address revolve around the effects of a "Eurocentric capitalist patriarchal culture built on the domination of nature, and the domination of woman 'as nature'. The writer Luke Martell in the Ecology and Society journal writes that 'women' and 'nature' are both victims of patriarchal abuse and "ideological products of the Enlightenment culture of control." Ecofeminism argues that we must become a part of nature, living with and among it. We must recognize that nature is alive and breathing and work against the passivity surrounding it that is synonymous with the passive roles enforced upon women by patriarchal culture, politics, and capitalism.

Catriona Sandilands is a Canadian writer and scholar in the environmental humanities. She is most well known for her conception of queer ecology. She is currently a Professor in the Faculty of Environmental Studies at York University. She was a Canada Research Chair in Sustainability and Culture between 2004 and 2014. She was a Fellow of the Pierre Elliott Trudeau Foundation in 2016. Sandilands served as president of the Association for the Study of Literature and Environment in 2015. She is also a past President of the Association for Literature, Environment, and Culture in Canada (ALECC) and the American Society for Literature and the Environment (ASLE).

Queer ecology is the endeavor to understand nature, biology, and sexuality in the light of queer theory, thus rejecting the presumption that heterosexuality and cisgenderedness constitute any objective standard. It draws from science studies, ecofeminism, environmental justice, and queer geography. These perspectives break apart various "dualisms" that exist within human understandings of nature and culture.

Alicia Helda Puleo García is an Argentine-born feminist philosopher based in Spain. She is known for the development of ecofeminist thinking. Among her main publications is Ecofeminismo para otro mundo posible.

Ecofeminism generally is based on the understanding that gender as a concept is the basis of the human-environment relationships. Studies suggest that there's a difference between men and women when it comes to how they treat nature, for instance, women are known to be more involved with environmentally friendly behaviors. Socially there's an important claim in the ecofeminism theoretical framework that the patriarchy is linked to discrimination against women and the degradation of the environment. In Canada the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and Toxics in 2020 shows that ineffective environmental management and mismanagement of hazardous waste is affecting different age groups, genders, and socioeconomic status in different ways, while three years before that, Canadian Human Rights Commission in 2017 submitted another report, warning the government about how the exposure to environmental hazards is a different experience for minorities in Canada. There have been ecofeminist movements for decades all over Canada such as Mother's Milk Project, protests against Uranium mining in Nova Scotia, and the Clayoquot Sound Peace Camp. Ecofeminism has also appeared as a concept in the media, such as books, publications, movies, and documentaries such as the MaddAddam trilogy by Margaret Atwood and Fury for the Sound: the women at Clayoquot by Shelley Wine. Ecofeminism in the Canadian context has been subject to criticism, especially by the Indigenous communities as they call it cultural appropriation, non-inclusive, and inherent in colonial worldviews and structures.