Radical feminism is a perspective within feminism that calls for a radical re-ordering of society in which male supremacy is eliminated in all social and economic contexts, while recognizing that women's experiences are also affected by other social divisions such as in race, class, and sexual orientation. The ideology and movement emerged in the 1960s.

Biphobia is aversion toward bisexuality or people who are identified or perceived as being bisexual. Similarly to homophobia, it refers to hatred and prejudice specifically against those identified or perceived as being in the bisexual community. It can take the form of denial that bisexuality is a genuine sexual orientation, or of negative stereotypes about people who are bisexual. Other forms of biphobia include bisexual erasure.

Lesbian feminism is a cultural movement and critical perspective that encourages women to focus their efforts, attentions, relationships, and activities towards their fellow women rather than men, and often advocates lesbianism as the logical result of feminism. Lesbian feminism was most influential in the 1970s and early 1980s, primarily in North America and Western Europe, but began in the late 1960s and arose out of dissatisfaction with the New Left, the Campaign for Homosexual Equality, sexism within the gay liberation movement, and homophobia within popular women's movements at the time. Many of the supporters of Lesbianism were actually women involved in gay liberation who were tired of the sexism and centering of gay men within the community and lesbian women in the mainstream women's movement who were tired of the homophobia involved in it.

Antisexualism is opposition or hostility towards sexual behavior and sexuality.

Cultural feminism is a term used to describe a variety of feminism that attempts to revalue and redefine attributes culturally ascribed to femaleness. It is also used to describe theories that commend innate differences between women and men.

Feminist separatism is the theory that feminist opposition to patriarchy can be achieved through women's separation from men. Much of the theorizing is based in lesbian feminism.

Black feminism is a branch of feminism that focuses on the African-American woman's experiences and recognizes the intersectionality of racism and sexism. Black feminism philosophy centers on the idea that "Black women are inherently valuable, that [Black women's] liberation is a necessity not as an adjunct to somebody else's but because of our need as human persons for autonomy."

"The Woman-Identified Woman" was a ten-paragraph manifesto, written by the Radicalesbians in 1970. It was first distributed during the Lavender Menace protest at the Second Congress to Unite Women, hosted by the National Organization for Women (NOW) on May 1, 1970, in New York City in response to the lack of lesbian representation at the congress. It is now considered a turning point in the history of radical feminism and one of the founding documents of lesbian feminism redefining the term "lesbian" as a political identity as well as a sexual one.

Sheila Jeffreys is a former professor of political science at the University of Melbourne, born in England. A lesbian feminist scholar, she analyses the history and politics of human sexuality.

Sarah Lucia Hoagland is the Bernard Brommel Distinguished Research Professor and Professor Emerita of Philosophy and Women's Studies at Northeastern Illinois University in Chicago.

The Furies Collective was a short-lived commune of twelve young lesbian separatists in Washington, D.C., in 1971 and 1972. They viewed lesbianism as more political than sexual, and declared heterosexual women to be an obstacle to the world revolution they sought. Their theories are still acknowledged among feminist groups.

Cell 16, started by Abby Rockefeller, was a progressive feminist organization active in the United States from 1968 to 1973, known for its program of celibacy, separation from men, and self-defense training. The organization had a journal: No More Fun and Games. Considered too extreme by establishment media, the organization was painted as hard left vanguard.

Radical lesbianism is a lesbian movement that challenges the status quo of heterosexuality and mainstream feminism. It arose in part because mainstream feminism did not actively include or fight for lesbian rights. The movement was started by lesbian feminist groups in the United States in the 1950s and 1960s. A Canadian movement followed in the 1970s, which added momentum. As it continued to gain popularity, radical lesbianism spread throughout Canada, the United States, and France. The French-based movement, Front des Lesbiennes Radicales, or FLR, organized in 1981 under the name Front des Lesbiennes Radicales. Other movements, such as Radicalesbians, have also stemmed off of the larger radical lesbianism movement. In addition to being associated with social movements, radical lesbianism also offers its own ideology, similar to how feminism functions in both capacities.

Julie Bindel is an English radical feminist writer. She is also co-founder of the law reform group Justice for Women, which has aimed to help women who have been prosecuted for assaulting or killing violent male partners.

Feminist views on sexuality widely vary. Many feminists, particularly radical feminists, are highly critical of what they see as sexual objectification and sexual exploitation in the media and society. Radical feminists are often opposed to the sex industry, including opposition to prostitution and pornography. Other feminists define themselves as sex-positive feminists and believe that a wide variety of expressions of female sexuality can be empowering to women when they are freely chosen. Some feminists support efforts to reform the sex industry to become less sexist, such as the feminist pornography movement.

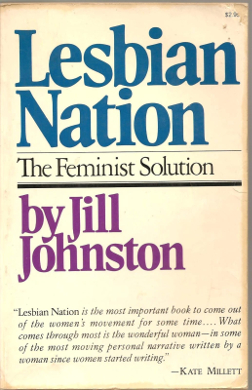

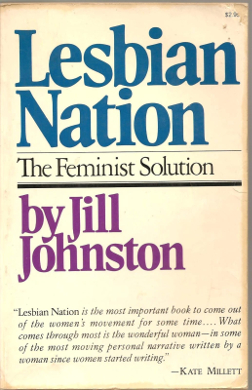

Lesbian Nation: The Feminist Solution is a 1973 book by the radical lesbian feminist author and cultural critic Jill Johnston. The book was originally published as a series of essays featured in The Village Voice from 1969 to 1972.

Onlywomen Press was a feminist press based in London. It was the only feminist press to be founded by out lesbians, Lilian Mohin, Sheila Shulman, and Deborah Hart. It commenced publishing in 1974 and was one of five notably active feminist publishers in the 1990s.

In feminist theory, heteropatriarchy or cisheteropatriarchy, is a socio-political system where (primarily) cisgender and heterosexual males have authority over other cisgender males, females, and people with other sexual orientations and gender identities. It is a term that emphasizes that discrimination against women and LGBT people is derived from the same sexist social principle.

The Leeds Revolutionary Feminist Group was a feminist organisation active in the United Kingdom in the 1970s and 1980s. While there were a number of contemporary revolutionary feminist organisations in the UK, the Leeds group was 'internationally significant'. The group is remembered chiefly for two reasons. The first is organising the UK-wide ‘Reclaim the Night’ marches in November 1977. The second is the publication of the pamphlet Political Lesbianism: The Case Against Heterosexuality, which advocated political lesbianism. British activist Sheila Jeffreys was closely involved with the group, while UK feminist Julie Bindel has spoken of the group's influence on her, as have many others.

Queer of color critique is an intersectional framework, grounded in Black feminism, that challenges the single-issue approach to queer theory by analyzing how power dynamics associated race, class, gender expression, sexuality, ability, culture and nationality influence the lived experiences of individuals and groups that hold one or more of these identities. Incorporating the scholarship and writings of Audre Lorde, Gloria Anzaldúa, Kimberlé Crenshaw, Barbara Smith, Cathy Cohen, Brittney Cooper and Charlene A. Carruthers, the queer of color critique asks: what is queer about queer theory if we are analyzing sexuality as if it is removed from other identities? The queer of color critique expands queer politics and challenges queer activists to move out of a "single oppression framework" and incorporate the work and perspectives of differently marginalized identities into their politics, practices and organizations. The Combahee River Collective Statement clearly articulates the intersecting forces of power: "The most general statement of our politics at the present time would be that we are actively committed to struggling against racial, sexual, heterosexual, and class oppression, and see as our particular task the development of integrated analysis and practice based upon the fact that major systems of oppression are interlocking. The synthesis of these oppressions creates the conditions of our lives." Queer of color critique demands that an intersectional lens be applied queer politics and illustrates the limitations and contradictions of queer theory without it. Exercised by activists, organizers, intellectuals, care workers and community members alike, the queer of color critique imagines and builds a world in which all people can thrive as their most authentic selves- without sacrificing any part of their identity.