AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power is an international, grassroots political group working to end the AIDS pandemic. The group works to improve the lives of people with AIDS through direct action, medical research, treatment and advocacy, and working to change legislation and public policies.

Queer Nation is an LGBTQ activist organization founded in March 1990 in New York City, by HIV/AIDS activists from ACT UP. The four founders were outraged at the escalation of anti-gay violence on the streets and prejudice in the arts and media. The group is known for its confrontational tactics, its slogans, and the practice of outing.

Gay Liberation Front (GLF) was the name of several gay liberation groups, the first of which was formed in New York City in 1969, immediately after the Stonewall riots. Similar organizations also formed in the UK, Australia and Canada. The GLF provided a voice for the newly-out and newly radicalized gay community, and a meeting place for a number of activists who would go on to form other groups, such as the Gay Activists Alliance, Gay Youth New York, and Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) in the US. In the UK and Canada, activists also developed a platform for gay liberation and demonstrated for gay rights. Activists from both the US and UK groups would later go on to found or be active in groups including ACT UP, the Lesbian Avengers, Queer Nation, Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, and Stonewall.

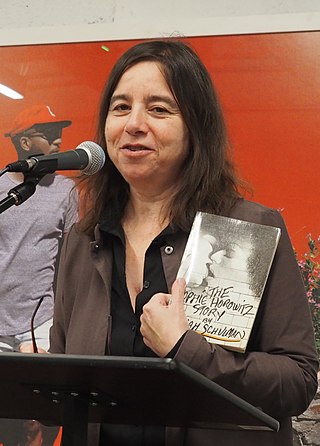

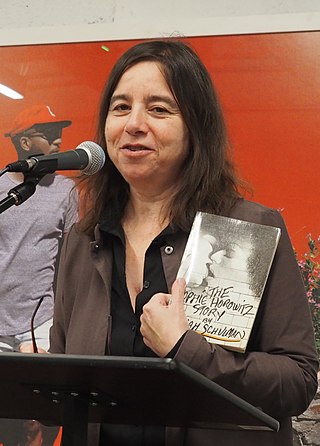

Sarah Miriam Schulman is an American novelist, playwright, nonfiction writer, screenwriter, gay activist, and AIDS historian. She holds an endowed chair in nonfiction at Northwestern University and is a fellow of the New York Institute for the Humanities. She is a recipient of the Bill Whitehead Award and the Lambda Literary Award.

A dyke march is a lesbian visibility and protest march, much like the original Gay Pride parades and gay rights demonstrations. The main purpose of a dyke march is the encouragement of activism within the lesbian and sapphic community. Dyke marches commonly take place the Friday or Saturday before LGBT pride parades. Larger metropolitan areas usually have several Pride-related happenings both before and after the march to further community building; with social outreach to specific segments such as older women, women of color, and lesbian parenting groups.

Moscow Pride is a demonstration of lesbians, gays, bisexuals, and transgender persons (LGBT). It was intended to take place in May annually since 2006 in the Russian capital Moscow, but has been regularly banned by Moscow City Hall, headed by Mayor Yuri Luzhkov until 2010. The demonstrations in 2006, 2007, and 2008 were all accompanied by homophobic attacks, which was avoided in 2009 by moving the site of the demonstration at the last minute. The organizers of all of the demonstrations were Nikolai Alekseev and the Russian LGBT Human Rights Project Gayrussia.ru. In June 2012, Moscow courts enacted a hundred-year ban on gay pride parades. The European Court of Human Rights has repeatedly ruled that such bans violate freedom of assembly guaranteed by the European Convention of Human Rights.

LGBT movements in the United States comprise an interwoven history of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and allied social movements in the United States of America, beginning in the early 20th century. A commonly stated goal among these movements is social equality for LGBT people. Some have also focused on building LGBT communities or worked towards liberation for the broader society from biphobia, homophobia, and transphobia. LGBT movements organized today are made up of a wide range of political activism and cultural activity, including lobbying, street marches, social groups, media, art, and research. Sociologist Mary Bernstein writes: "For the lesbian and gay movement, then, cultural goals include challenging dominant constructions of masculinity and femininity, homophobia, and the primacy of the gendered heterosexual nuclear family (heteronormativity). Political goals include changing laws and policies in order to gain new rights, benefits, and protections from harm." Bernstein emphasizes that activists seek both types of goals in both the civil and political spheres.

Ana María Simo is a New York playwright, essayist and novelist. Born in Cuba, educated in France, and writing in English, she has collaborated with such experimental artists as composer Zeena Parkins, choreographer Stephanie Skura and filmmakers Ela Troyano and Abigail Child.

Dyke is a slang term, used as a noun meaning lesbian. It originated as a homophobic slur for masculine, butch, or androgynous girls or women. Pejorative use of the word still exists, but the term dyke has been reappropriated by many lesbians to imply assertiveness and toughness.

On 9 September 1971 the UK Gay Liberation Front (GLF) undertook an action to disrupt the launch of the Church-based morality campaign Nationwide Festival of Light at the Methodist Central Hall, Westminster. A number of well-known British figures were involved in the disrupted rally, and the action involved the use of "radical drag" drawing on the Stonewall riots and subsequent GLF actions in the US. Peter Tatchell, gay human rights campaigner, was involved in the action which was one of a series which influenced the development of gay activism in the UK, received media attention at the time, and is still discussed by some of those involved.

Carrie Moyer is an American painter and writer living in Brooklyn, New York. Moyer's paintings and public art projects have been exhibited both in the US and Europe since the early 1990s, and she is best known for her 17-year agitprop project, Dyke Action Machine! with photographer Sue Schaffner. Moyer's work has been shown at the Whitney Biennial, the Museum of Arts and Design, and the Tang Museum, and is held in the permanent collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. She serves as the director of the graduate MFA program at Hunter College, and has contributed writing to anthologies and publications like The Brooklyn Rail and Artforum.

Dyke Action Machine! or DAM! is a public art and activist duo made up of painter and graphic designer Carrie Moyer and photographer Sue Schaffner. DAM! gained notoriety in the 1990s for using commercial photography styling with lesbian imagery in public art.

Dyke TV was founded and created by Ana María Simo, playwright and cofounder of Lesbian Avengers; Linda Chapman, theater director and producer; and Mary Patierno, independent film and video maker.

The Transexual Menace, or The Menace, was a transgender rights activist organization founded in New York City in 1993. It was the first direct action group of its kind, and grew to be a national organisation with 24 chapters.

The Gay and Lesbian Organization of Witwatersrand (GLOW) was a non-governmental organization in South Africa that focused on gay and lesbian community issues.

The National LGBTQ Wall of Honor is a memorial wall in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Manhattan in New York City, dedicated to LGBTQ "pioneers, trailblazers, and heroes". Located inside the Stonewall Inn, the wall is part of the Stonewall National Monument, the first U.S. National Monument dedicated to the country's LGBTQ rights and history. The first fifty nominees were announced in June 2019, and the wall was unveiled on June 27, 2019, as a part of Stonewall 50 – WorldPride NYC 2019 events. Five honorees will be added annually.

Ortez Alderson was an American AIDS, gay rights, and anti-war activist and actor. A member of LGBT community, he was a leader of the Black Caucus of the Chicago Gay Liberation Front, which later became the Third World Gay Revolution, and served a federal prison sentence for destroying files related to the draft for the Vietnam War. In 1987, he was one of the founding members of ACT UP in New York City, and helped to establish its Majority Action Committee representing people of color with HIV and AIDS. Regarded as a "radical elder" within ACT UP, he was involved in organizing numerous demonstrations in the fight for access to healthcare and treatments for people with AIDS, and participated in the group's meetings with NYC Health Commissioner Stephen Joseph as well as the FDA. In 1989, he moved back to Chicago and helped to organize the People of Color and AIDS Conference the following year. He died of complications from AIDS in 1990, and was inducted posthumously into the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame.

Queer radicalism can be defined as actions taken by queer groups which contribute to a change in laws and/or social norms. The key difference between queer radicalism and queer activism is that radicalism is often disruptive, and commonly involves illegal action. Due to the nature of LGBTQ+ laws around the world, almost all queer activism that took place before the decriminalization of gay marriage can be considered radical action. The history of queer radicalism can be expressed through the many organizations and protests that contributed to a common cause of improving the rights and social acceptance of the LGBTQ+ community.

On September 26, 1992, Hattie Mae Cohens and Brian Mock were killed by a firebomb attack at their apartment in Salem, Oregon.