LGBT is an initialism that stands for "lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender". It may refer to anyone who is non-heterosexual, non-heteroromantic, or non-cisgender, instead of exclusively to people who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender. A variant, LGBTQ, adds the letter Q for those who identify as queer or are questioning their sexual or gender identity. Another variation, LGBTQ+, adds a plus sign "represents those who are part of the community, but for whom LGBTQ does not accurately capture or reflect their identity". Many further variations of the acronym exist, such as LGBT+, LGBTQIA+, and 2SLGBTQ+. The LGBT label is not universally agreed to by everyone that it is generally intended to include. The variations GLBT and GLBTQ rearrange the letters in the acronym. In use since the late 1980s, the initialism, as well as some of its common variants, functions as an umbrella term for marginalized sexualities and gender identities.

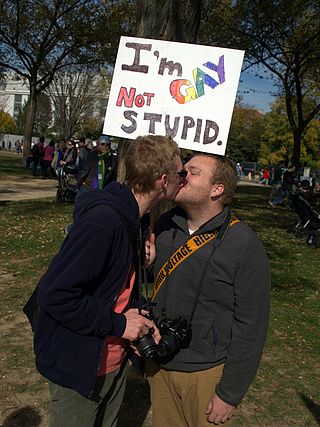

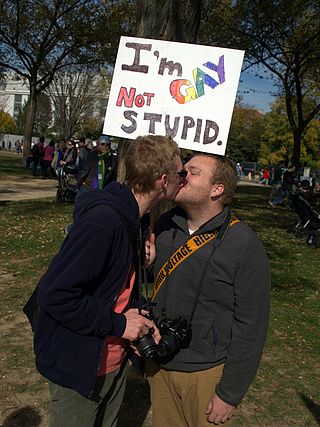

The LGBT community is a loosely defined grouping of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals united by a common culture and social movements. These communities generally celebrate pride, diversity, individuality, and sexuality. LGBT activists and sociologists see LGBT community-building as a counterweight to heterosexism, homophobia, biphobia, transphobia, sexualism, and conformist pressures that exist in the larger society. The term pride or sometimes gay pride expresses the LGBT community's identity and collective strength; pride parades provide both a prime example of the use and a demonstration of the general meaning of the term. The LGBT community is diverse in political affiliation. Not all people who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender consider themselves part of the LGBT community.

Femme is a term traditionally used to describe a lesbian woman who exhibits a feminine identity or gender presentation. While commonly viewed as a lesbian term, alternate meanings of the word also exist with some non-lesbian individuals using the word, notably some gay men and bisexuals. Some non-binary and transgender individuals also identify as lesbians using this term.

LGBT culture is a culture shared by lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer individuals. It is sometimes referred to as queer culture, while the term gay culture may be used to mean either "LGBT culture" or homosexual culture specifically.

Terms used to describe homosexuality have gone through many changes since the emergence of the first terms in the mid-19th century. In English, some terms in widespread use have been sodomite, Achillean, Sapphic, Uranian, homophile, lesbian, gay, effeminate, queer, homoaffective, and same-gender attracted. Some of these words are specific to women, some to men, and some can be used of either. Gay people may also be identified under the umbrella term LGBT.

Sexual attraction to transgender people has been the subject of scientific study and social commentary. Psychologists have researched sexual attraction toward trans women, trans men, cross dressers, non-binary people, and a combination of these. Publications in the field of transgender studies have investigated the attraction transgender individuals can feel for each other. The people who feel this attraction to transgender people name their attraction in different ways.

LGBT stereotypes are stereotypes about lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people are based on their sexual orientations, gender identities, or gender expressions. Stereotypical perceptions may be acquired through interactions with parents, teachers, peers and mass media, or, more generally, through a lack of firsthand familiarity, resulting in an increased reliance on generalizations.

Over the course of its history, the LGBT community has adopted certain symbols for self-identification to demonstrate unity, pride, shared values, and allegiance to one another. These symbols communicate ideas, concepts, and identity both within their communities and to mainstream culture. The two symbols most recognized internationally are the pink triangle and the rainbow flag.

Homophobia encompasses a range of negative attitudes and feelings toward homosexuality or people who identify or are perceived as being lesbian, gay or bisexual. It has been defined as contempt, prejudice, aversion, hatred or antipathy, may be based on irrational fear and may sometimes be attributed to religious beliefs.

Bisexual erasure, also called bisexual invisibility, is the tendency to ignore, remove, falsify, or re-explain evidence of bisexuality in history, academia, the news media, and other primary sources.

New Zealand society is generally accepting of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) peoples. The LGBT-friendly environment is epitomised by the fact that there are several members of Parliament who belong to the LGBT community, LGBT rights are protected by the Human Rights Act, and same-sex couples are able to marry as of 2013. Sex between men was decriminalised in 1986. New Zealand has an active LGBT community, with well-attended annual gay pride festivals in most cities.

LGBT movements in the United States comprise an interwoven history of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and allied social movements in the United States of America, beginning in the early 20th century. A commonly stated goal among these movements is social equality for LGBT people. Some have also focused on building LGBT communities or worked towards liberation for the broader society from biphobia, homophobia, and transphobia. LGBT movements organized today are made up of a wide range of political activism and cultural activity, including lobbying, street marches, social groups, media, art, and research. Sociologist Mary Bernstein writes: "For the lesbian and gay movement, then, cultural goals include challenging dominant constructions of masculinity and femininity, homophobia, and the primacy of the gendered heterosexual nuclear family (heteronormativity). Political goals include changing laws and policies in order to gain new rights, benefits, and protections from harm." Bernstein emphasizes that activists seek both types of goals in both the civil and political spheres.

Various topics in medicine relate particularly to the health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex and asexual (LGBTQIA) individuals as well as other sexual and gender minorities. According to the US National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center, these areas include sexual and reproductive health, mental health, substance use disorders, HIV/AIDS, HIV-related cancers, intimate partner violence, issues surrounding marriage and family recognition, breast and cervical cancer, inequities in healthcare and access to care. In medicine, various nomenclature, including variants of the acronym LGBTQIA+, are used as an umbrella term to refer to individuals who are non-heterosexual, non-heteroromantic, or non-cis gendered. Specific groups within this community have their own distinct health concerns, however are often grouped together in research and discussions. This is primarily because these sexual and gender minorities groups share the effects of stigmatization based on their gender identity or expression, and/or sexual orientation or affection orientation. Furthermore, there are subpopulations among LGBTQIA+ groups based on factors such as race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, geographic location, and age, all of which can impact healthcare outcomes.

LGBT linguistics is the study of language as used by members of LGBT communities. Related or synonymous terms include lavender linguistics, advanced by William Leap in the 1990s, which "encompass[es] a wide range of everyday language practices" in LGBT communities, and queer linguistics, which refers to the linguistic analysis concerning the effect of heteronormativity on expressing sexual identity through language. The former term derives from the longtime association of the color lavender with LGBT communities. "Language", in this context, may refer to any aspect of spoken or written linguistic practices, including speech patterns and pronunciation, use of certain vocabulary, and, in a few cases, an elaborate alternative lexicon such as Polari.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer+(LGBTQ+)music is music that focuses on the experiences of gender and sexual minorities as a product of the broad gay liberation movement.

Discrimination against gay men, sometimes called gayphobia, is a form of homophobic prejudice, hatred, or bias specifically directed toward gay men, male homosexuality, or men who are perceived to be gay. This discrimination is closely related to femmephobia, which is the dislike of, or hostility toward, individuals who present as feminine, including gay and effeminate men.

The following outline offers an overview and guide to LGBT topics.

The African-American LGBT community, otherwise referred to as the Black American LGBT community, is part of the overall LGBT culture and overall African-American culture. The initialism LGBT stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender.

Gender and sexual diversity (GSD), or simply sexual diversity, refers to all the diversities of sex characteristics, sexual orientations and gender identities, without the need to specify each of the identities, behaviors, or characteristics that form this plurality.

LGBT erasure refers to the tendency to intentionally or unintentionally remove LGBT groups or people from record, or downplay their significance, which includes lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender people and those who identify as queer. This erasure can be found in a number of written and oral texts, including popular and scholarly texts.