Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians including recruited children, use ambushes, sabotage, terrorism, raids, petty warfare or hit-and-run tactics in a rebellion, in a violent conflict, in a war or in a civil war to fight against regular military, police or rival insurgent forces.

The Cuban Revolution was a military and political effort to overthrow the government of Cuba between 1953 and 1959. It began after the 1952 Cuban coup d'état which placed Fulgencio Batista as head of state. After failing to contest Batista in court, Fidel Castro organized an armed attack on the Cuban military's Moncada Barracks on July 26, 1953. The rebels were arrested and while in prison formed the 26th of July Movement (M-26-7). After gaining amnesty the M-26-7 rebels organized an expedition from Mexico on the Granma yacht to invade Cuba. In the following years the M-26-7 rebel army would slowly defeat the Cuban army in the countryside, while its urban wing would engage in sabotage and rebel army recruitment. Over time the originally critical and ambivalent Popular Socialist Party would come to support the 26th of July Movement in late 1958. By the time the rebels were to oust Batista the revolution was being driven by the Popular Socialist Party, 26th of July Movement, and the Revolutionary Directorate of March 13.

The 26th of July Movement was a Cuban vanguard revolutionary organization and later a political party led by Fidel Castro. The movement's name commemorates the failed 1953 attack on the Moncada Barracks in Santiago de Cuba, part of an attempt to overthrow the dictator Fulgencio Batista.

An urban guerrilla is someone who fights a government using unconventional warfare or terrorism in an urban environment.

Celia Sánchez Manduley was a Cuban revolutionary, politician, researcher and archivist. She was a key member of the Cuban Revolution and a close colleague of Fidel Castro.

Sandinista ideology or Sandinismo is a series of political and economic philosophies instituted by the Nicaraguan Sandinista National Liberation Front throughout the late twentieth century. The ideology and movement acquired its name, image and its military style from Augusto César Sandino, a Nicaraguan revolutionary leader who waged a guerrilla war against the United States Marines and the conservative Somoza National Guards in the early twentieth century. The principals of modern Sandinista ideology were mainly developed by Carlos Fonseca, inspired by the leaders of the Cuban Revolution in the 1950s. It sought to inspire socialist populism among Nicaragua's peasant population. One of these main philosophies involved the institution of an educational system that would free the population from the perceived historical fallacies spread by the ruling Somoza family. By awakening political thought among the people, proponents of Sandinista ideology believed that human resources would be available to not only execute a guerrilla war against the Somoza regime but also build a society resistant to economic and military intervention imposed by foreign entities.

The Cuban Revolution was the overthrow of Fulgencio Batista's regime by the 26th of July Movement and the establishment of a new Cuban government led by Fidel Castro in 1959.

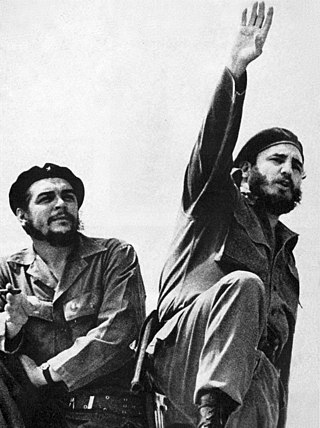

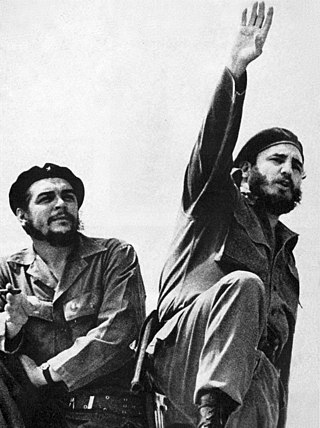

Guerrilla Warfare is a military handbook written by Marxist–Leninist revolutionary Che Guevara. Published in 1961 following the Cuban Revolution, it became a reference for thousands of guerrilla fighters in various countries around the world. The book draws upon Guevara's personal experience as a guerrilla soldier during the Cuban Revolution, generalizing for readers who would undertake guerrilla warfare in their own countries.

Ernesto "Che" Guevara was an Argentine Marxist revolutionary, physician, author, guerrilla leader, diplomat, and military theorist. A major figure of the Cuban Revolution, his stylized visage has become a ubiquitous countercultural symbol of rebellion and global insignia in popular culture.

The legacy of Argentine Marxist revolutionary Che Guevara is constantly evolving in the collective imagination. As a symbol of counterculture worldwide, Guevara is one of the most recognizable and influential revolutionary figures of the twentieth century. However, during his life, and even more since his death, Che has elicited controversy and wildly divergent opinions on his personal character and actions. He has been both revered and reviled, being characterized as everything from a heroic defender of the poor, to a cold-hearted executioner.

Ernesto "Che" Guevara, was an Argentine Marxist revolutionary, politician, author, intellectual, physician, military theorist, and guerrilla leader. His life, legacy, and ideas have attracted a great deal of interest from historians, artists, film makers, musicians, and biographers. In reference to the abundance of material, Nobel Prize–winning author Gabriel García Márquez has declared that "it would take a thousand years and a million pages to write Che's biography."

Third World socialism is a political philosophy and variant of socialism that has been proposed by Michel Aflaq, Salah al-Din al-Bitar, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, Buddhadasa, Fidel Castro, Muammar Gaddafi, Saddam Hussein, Juan Domingo Perón, Modibo Keïta, Walter Lini, Gamal Abdel Nasser, Jawaharlal Nehru, Kwame Nkrumah, Julius Nyerere, Sukarno, Ahmed Sékou Touré and other socialist leaders of the Third World who saw socialism as the answer to a strong and developed nation.

Mario Roberto Santucho was an Argentine revolutionary and guerrilla combatant, founder of the Partido Revolucionario de los Trabajadores and leader of Argentina's largest Marxist guerrilla group, the Ejército Revolucionario del Pueblo.

Abraham Guillén, was a Spanish author, economist, and educator. He was a veteran of the Spanish Civil War, influenced by anarchism. One of the most prolific revolutionary writers in Latin America during the 1960s and intellectual mentor of Uruguay's revolutionary Movement of National Liberation (Tupamaros), he is most widely known as the author of Strategy of the Urban Guerrilla, which played an important role in the activities of urban guerrillas in Uruguay, Argentina, and Brazil.

The Ñancahuazú Guerrilla or Ejército de Liberación Nacional de Bolivia was a group of mainly Bolivian and Cuban guerrillas led by the guerrilla leader Che Guevara which was active in the Cordillera Province of Bolivia from 1966 to 1967. The group established its base camp on a farm across the Ñancahuazú River, a seasonal tributary of the Rio Grande, 250 kilometers southwest of the city of Santa Cruz de la Sierra. The guerrillas intended to work as a foco, a point of armed resistance to be used as a first step to overthrow the Bolivian government and create a socialist state. The guerrillas defeated several Bolivian patrols before they were beaten and Guevara was captured and executed. Only five guerrillas managed to survive, including Harry Villegas, and fled to Chile.

The Cuban communist revolutionary and politician Fidel Castro took part in the Cuban Revolution from 1953 to 1959. Following on from his early life, Castro decided to fight for the overthrow of Fulgencio Batista's military junta by founding a paramilitary organization, "The Movement". In July 1953, they launched a failed attack on the Moncada Barracks, during which many militants were killed and Castro was arrested. Placed on trial, he defended his actions and provided his famous "History Will Absolve Me" speech, before being sentenced to 15 years' imprisonment in the Model Prison on the Isla de Pinos. Renaming his group the "26th of July Movement" (MR-26-7), Castro was pardoned by Batista's government in May 1955, claiming they no longer considered him a political threat while offering to give him a place in the government, but he refused. Restructuring the MR-26-7, he fled to Mexico with his brother Raul Castro, where he met with Argentine Marxist-Leninist Che Guevara, and together they put together a small revolutionary force intent on overthrowing Batista.

Guevarism is a theory of communist revolution and a military strategy of guerrilla warfare associated with Marxist–Leninist revolutionary Ernesto "Che" Guevara, a leading figure of the Cuban Revolution who believed in the idea of Marxism–Leninism and embraced its principles.

The Party of the Poor was a left-wing political movement and militant group in Mexico operating between 1967 and 1974. Led by the rural schoolteacher Lucio Cabañas, the PdlP – through its armed wing, the Peasants' Justice Brigade – waged guerrilla warfare against the Mexican government in the mountains of Guerrero.

Tendencia Revolucionaria, Tendencia Revolucionaria Peronista, or simply la Tendencia or revolutionary Peronism, was the name given in Argentina to a current of Peronism grouped around the guerrilla organisations FAR, FAP, Montoneros and the Juventud Peronista. Formed progressively in the 1960s and 1970s, and so called at the beginning of 1972, it was made up of various organisations that adopted a combative and revolutionary stance, in which Peronism was conceived as a form of Christian socialism, adapted to the situation in Argentina, as defined by Juan Perón himself. The Tendencia was supported and promoted by Perón, during the final stage of his exile, because of its ability to combat the dictatorship that called itself the Argentine Revolution. It had a great influence in the Peronist Resistance (1955-1973) and the first stage of Third Peronism, when Héctor J. Cámpora was elected President of the Nation on 11 March 1973.

The consolidation of the Cuban Revolution is a period in Cuban history typically defined as starting in the aftermath of the revolution in 1959 and ending in the first congress of the Communist Party of Cuba 1975, which signified the final political solidification of the Cuban revolutionaries' new government. The period encompasses early domestic reforms, human rights violations continuing under the new regime, growing international tensions, and politically climaxed with the failure of the 1970 sugar harvest.