Hugo Rafael Chávez Frías was a Venezuelan politician and military officer who served as president of Venezuela from 1999 until his death in 2013, except for a brief period of forty-seven hours in 2002. Chávez was also leader of the Fifth Republic Movement political party from its foundation in 1997 until 2007, when it merged with several other parties to form the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV), which he led until 2012.

The Supreme Justice Tribunal is the highest court of law in the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela and is the head of the judicial branch. As the independence of the Venezuelan judiciary under the regime of Nicolás Maduro is questioned, there have recently been many disputes as to whether this court is legitimate.

María Corina Machado Parisca is a Venezuelan opposition politician and industrial engineer who served as an elected member of the National Assembly of Venezuela from 2011 to 2014. Machado was the founder and former leader of the Venezuelan volunteer civil organization Súmate, alongside Alejandro Plaz. In 2018, she was listed as one of BBC's 100 Women.

Chavismo, also known in English as Chavism or Chavezism, is a left-wing populist political ideology based on the ideas, programs and government style associated with the Venezuelan President between 1999 and 2013 Hugo Chávez that combines elements of democratic socialism, socialist patriotism, Bolivarianism, and Latin American integration. People who supported Hugo Chávez and Chavismo are known as Chavistas.

The Bolivarian National Guard of Venezuela, is a gendarmerie component of the National Armed Forces of Venezuela. The national guard can serve as gendarmerie, perform civil defense roles, or serve as a reserve light infantry force. The national guard was founded on 4 August 1937 by the then President of the Republic, General-in-Chief Eleazar López Contreras. The motto of the GNB is "El Honor es su divisa", slightly different from the motto of the Spanish Civil Guard "El Honor es mi divisa".

The level of corruption in Venezuela is very high by world standards and is prevalent throughout many levels of Venezuelan society. Discovery of oil in Venezuela in the early 20th century has worsened political corruption. The large amount of corruption and mismanagement in the country has resulted in severe economic difficulties, part of the crisis in Venezuela. A 2014 Gallup poll found that 75% of Venezuelans believed that corruption was widespread throughout the Venezuelan government. Discontent with corruption was cited by demonstrators as one of the reasons for the 2014 and 2017 Venezuelan protests.

Crime in Venezuela is widespread, with violent crimes such as murder and kidnapping increasing for several years. In 2014, the United Nations attributed crime to the poor political and economic environment in the country—which, at the time, had the second highest murder rate in the world. Rates of crime rapidly began to increase during the presidency of Hugo Chávez due to the institutional instability of his Bolivarian government, underfunding of police resources, and severe inequality. Chávez's government sought a cultural hegemony by promoting class conflict and social fragmentation, which in turn encouraged "criminal gangs to kill, kidnap, rob and extort". Upon Chávez's death in 2013, Venezuela was ranked the most insecure nation in the world by Gallup.

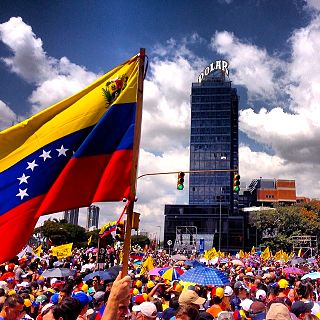

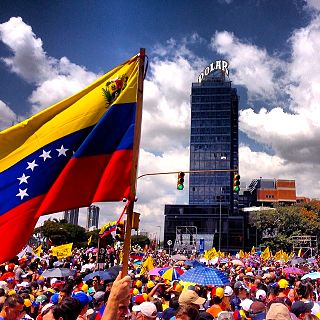

In 2014, a series of protests, political demonstrations, and civil insurrection began in Venezuela due to the country's high levels of urban violence, inflation, and chronic shortages of basic goods and services. Explanations for these worsening conditions vary, with analysis blaming strict price controls, alongside long-term, widespread political corruption resulting in the under-funding of basic government services. While protests first occurred in January, after the murder of actress and former Miss Venezuela Mónica Spear, the 2014 protests against Nicolás Maduro began in earnest that February following the attempted rape of a student on a university campus in San Cristóbal. Subsequent arrests and killings of student protesters spurred their expansion to neighboring cities and the involvement of opposition leaders. The year's early months were characterized by large demonstrations and violent clashes between protesters and government forces that resulted in nearly 4,000 arrests and 43 deaths, including both supporters and opponents of the government. Toward the end of 2014, and into 2015, continued shortages and low oil prices caused renewed protesting.

Colectivos are far-left Venezuelan armed paramilitary groups that support the Bolivarian government, the Great Patriotic Pole (GPP) political alliance and Venezuela's ruling party, and the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV). Colectivo has become an umbrella term for irregular armed groups that operate in poverty-stricken areas.

23 de Enero is a parish located in the Libertador Bolivarian Municipality west of the city of Caracas, Venezuela. The parish receives its name from the date of the 1958 Venezuelan coup d'état which overthrew dictator Marcos Pérez Jiménez.

2016 protests in Venezuela began in early January following controversy surrounding the 2015 Venezuelan parliamentary elections and the increasing hardships felt by Venezuelans. The series of protests originally began in February 2014 when hundreds of thousands of Venezuelans protested due to high levels of criminal violence, inflation, and chronic scarcity of basic goods because of policies created by the Venezuelan government though the size of protests had decreased since 2014.

The 2017 Venezuelan protests began in late January following the abandonment of Vatican-backed dialogue between the Bolivarian government and the opposition. The series of protests originally began in February 2014 when hundreds of thousands of Venezuelans protested due to high levels of criminal violence, inflation, and chronic scarcity of basic goods because of policies created by the Venezuelan government though the size of protests had decreased since 2014. Following the 2017 Venezuelan constitutional crisis, protests began to increase greatly throughout Venezuela.

On 29 March 2017, the Supreme Tribunal of Justice (TSJ) of Venezuela took over legislative powers of the National Assembly. The Tribunal, mainly supporters of President Nicolás Maduro, also restricted the immunity granted to the Assembly's members, who mostly belonged to the opposition.

The 2017 Venezuelan protests were a series of protests occurring throughout Venezuela. Protests began in January 2017 after the arrest of multiple opposition leaders and the cancellation of dialogue between the opposition and Nicolás Maduro's government.

On 27 June 2017, there was an incident involving a police helicopter at the Supreme Tribunal of Justice (TSJ) and Interior Ministry in Caracas, Venezuela. Claiming to be a part of an anti-government coalition of military, police and civilians, the occupants of the helicopter allegedly launched several grenades and fired at the building, although no one was injured or killed. President Nicolás Maduro called the incident a "terrorist attack". The helicopter escaped and was found the next day in a rural area. On 15 January 2018, Óscar Pérez, the pilot and instigator of the incident, was killed during a military raid by the Venezuelan army that was met with accusations of extrajudicial killing.

Óscar Alberto Pérez was a Venezuelan rebel leader and an investigator for the CICPC, Venezuela's investigative agency. He was also an actor in a film to promote the role of detectives in the CICPC. He is better known for being responsible for the Caracas helicopter incident during the 2017 Venezuelan protests and the 2017 Venezuelan constitutional crisis. His killing in the El Junquito raid received worldwide attention by the media and the political establishment, and was met with accusations of extrajudicial killing.

Parliamentary elections were held in Venezuela on 6 December 2020. Aside from the 167 deputies of the National Assembly who are eligible to be re-elected, the new National Electoral Council president announced that the assembly would increase by 110 seats, for a total of 277 deputies to be elected.

La Piedrita is a colectivo that is active in Venezuela. It has been described as one of the most violent and influential colectivos in Venezuela. The colectivo has stated that they will defend the Bolivarian revolution "at all costs".

Chavismo: The Plague of the 21st Century is a 2018 documentary film directed by Gustavo Tovar-Arroyo. The film is an analysis of the causes, social, political and economic that caused the rise of Hugo Chávez as president of Venezuela; his abuse of power and the response of civil society, including the student movement; his political fall as well as the secrecy that surrounded his illness and the succession of Nicolás Maduro.

Coups d'état in Venezuela have occurred almost since the foundation of the Republic. Throughout the history of Venezuela, insurrections, uprisings, or military or civil revolutions were used to overthrow and replace governments. These coups were performed using force, intimidation, and pseudo-legal methods. Gradually with the consolidation of a democratic system in the country, coups became less and less common.