History

The term 'formalism' originally pertains to late-nineteenth-century debates in the philosophy of mathematics, but these discussions would also lead to the development of formal syntax and formal semantics. In such debates, advocates of psychologism argued that arithmetic arises from human psychology, claiming that there are no absolute mathematical truths. Thus, in principle, an equation like 1 + 1 = 2 depends on a human way of thinking and therefore cannot have objective value. So was argued by psychologist Wilhelm Wundt among others. Many mathematicians disagreed and proposed "formalism" which considered mathematical sequences and operations as purely axiomatic with no mental content and thus disconnected from human psychology.

Edmund Husserl disagreed with both claims. He argued that both cardinal numbers and arithmetic operations are fundamentally meaningful, and that our ability to carry out complex mathematical tasks is based on the extension of simple concepts such as low non-imaginary numbers, addition, subtraction, and so on. Based on mathematical logic, Husserl also created a "formal semantics" arguing that linguistic meaning is composed of series of logical propositions. Additionally, he argued on the one hand that human thought, and thus the world as we perceive it, is similarly composed; and on the other, that syntax is also composed of logical propositions. [10]

Advocates of early formalism had compared mathematics to a game of chess where all valid moves are based on a handful of arbitrary rules void of any truly meaningful content. In his Course in General Linguistics (posthumous, 1916), Ferdinand de Saussure likewise compares the grammatical rules of a language to a game of chess, suggesting he may have been familiar with "game formalism". He however develops the idea to a different direction, attempting to demonstrate that each synchronic state of a language is similar to a chess composition in that its history is irrelevant to the players. Unlike the mathematical formalists, Saussure considers all signs as meaningful by definition, and argues that the "rules"—in his thesis, laws of the semiotic system—are universal and eternal. [11] Thus, he is not talking about specific grammatical rules, but constant phenomena such as analogy and opposition.

In 1943, Louis Hjelmslev combined Saussure's concept of the bilateral sign (meaning + form) with Rudolph Carnap's mathematical grammars. Hjelmslev was deeply influenced by the functional linguistics of the Prague linguistic circle, considering pragmatics as integral to grammar. Some advocates of functional linguistics however disagreed with Hjelmslev's logico-mathematical approach and his terminology where the word 'function' indicates a mere structural dependency in contradistinction with classical functionalism where it means 'purpose'. Hjelmslev was consequently called "formalist". [12] In such reference, Hjelmslevian "formalism" is closer to Husserlian logicism than game formalism because semantics constitutes one the two fundamental planes of his notion of language.

Again, Roman Jakobson, who was indeed a member of the Prague functionalist school, was also an advocate of a literary theory or movement called Russian formalism. This approach was not particularly mathematical, but aimed at analyzing the text in its own right. It received this name from its opponents who considered it as falsely separating literature from psychology.

Wundt's idea of analyzing culture as the product of psychology was rejected by his successors in Europe. [13] In mathematics, most scholars at the time sided with Husserl, although today philosopher Martin Kusch argues that Husserl failed to deliver a definitive refutation of psychologism. [7] European structural and functional linguists agreed with Husserl and Saussure, both opposed to Wundt's psychological–historical view of language, giving semantics a core explanatory role in their linguistic theories.Interest in mathematical linguistics nonetheless remained limited in general linguistics in Europe.

The situation was different in the US where Franz Boas imported Wundt's ideas to form the Boasian school of anthropology. His students included linguists Edward Sapir and Benjamin Whorf. Leonard Bloomfield, on the other hand, traveled to Germany to attend Wundt's lectures in linguistics. Based on his ideas, Bloomfield wrote his 1914 textbook An Introduction to the Study of Language becoming the leading figure in American linguistics until his death in 1949. [14] Bloomfield proposed a "philosophical-descriptive" approach to the study of language suggesting that the linguist's task is to document and analyze linguistic samples leaving further theoretical questions to psychologists. [15]

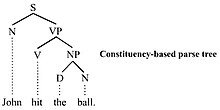

The post-Bloomfieldian school of the 1950s was also increasingly keen on mathematical linguistics. Based on Carnap's model of arithmetic syntax, Zellig Harris and Charles Hockett proposed a version of generative grammar whose ultimate purpose is just to generate grammatical word sequences. They advocated distributionalism as an attempt to define syntactic constitutes. It was suggested, for example, that a noun phrase like a beautiful home is not based on its meaning constitution, but on the fact that such words (determiner, adjective, noun) tend to appear jointly in texts. [16] This attempt was abandoned after Noam Chomsky proposed that the study of syntax is the study of knowledge of language, and therefore a cognitive science. His justification for the analysis became that the syntactic structures uncovered by a generative linguist are innate and based on a random genetic mutation. [17] Chomsky has argued since the beginning that mathematics has no explanatory value for linguistics which he defines as a sub-field of cognitive psychology. Therefore, his approach is opposed to game formalism.

"When generative grammar was being first developed, a language was defined as a set of sentences, generated by the rules of a grammar, where ‘‘generated’’ is a term taken over from mathematics and just means formally or rigorously described [...} Chomsky’s early work included a demonstration that any such definition of language could not have a decisive role to play in linguistic theory." [18]

In other words, Chomsky's psychologism replaced mathematical formalism in generative linguistics in the 1960s. Chomsky does not however argue against formalism or logicism in mathematics, only that such approaches are not relevant to the study of natural language. He is nonetheless interested in the precise form of the correct syntactic representation. When developing his theory, Chomsky took influences from molecular biology. [19] More recently, he has described "universal grammar" as having a crystalline form, comparing it to a snowflake. [20] In other words, a formalism (i.e. a syntactic model) is used to reveal hidden patterns or symmetries underlying human language. This practice became opposed by American "functionalism" which argues that language is not crystallized but dynamic and ever-changing. [21] This type of functionalism includes various frameworks which are inspired by memetics and linked with the cognitive linguistics of George Lakoff and his associates. [22] [23] Like Wundt, Lakoff also proposes a psychologism for mathematics. [24]

Some frameworks advocating mathematical formalism do however exist today. Categorial grammar is a type of generative grammar which was developed by mathematicians and logicians including by Kazimierz Ajdukiewicz, Yehoshua Bar-Hillel, and Joachim Lambek. Their method includes a separate model for syntax and semantics. Thus, even categorial grammar includes a meaningful component. It is however not psychologistic because it does not claim that syntactic structures stem from human psychology; nor is it logicistic because, unlike Husserl, it does not consider structures of natural language as being logical. Furthermore, unlike structuralism, their approach adheres to a mathematical rather than a semiotic view of language. Such a framework, then, is purely descriptivist and atheoretical—that is, it does not aim to explain why languages are the way they are—or only theoretical as pertains to the concept of the word 'theory' in mathematics, especially model theory.

Ideas

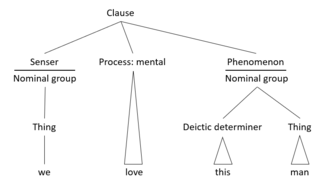

A central assumption of linguistic formalism, and of generative linguistics in particular, is called the autonomy of syntax, according to which syntactic structures are built by operations which make no reference to meaning, discourse, or use. [25] In one formulation, this notion is defined as syntax being arbitrary and self-contained with respect to meaning, semantics, pragmatics, and other factors external to language. [26] Because of this, those approaches that adopt that assumption have also been called autonomist linguistics. The assumption of the autonomy of syntax is what most prominently distinguishes linguistic formalism from linguistic functionalism, and it is at the core of the debate between the two. [26] Over the decades, multiple instances have been found of cases in which syntactic structures are actually determined or influenced by semantic traits, and some formalists and generativits have reacted to that by shrinking those parts of semantics that they consider autonomous. Over the decades, in the changes that Noam Chomsky has made to his generative formulation, there has been a shift from a claim of the autonomy of the syntax to that of an autonomy of grammar. [26]

Another central idea of linguistic formalism is that human language can be defined as a formal language like the language of mathematics and programming languages. Additionally, formal rules can be applied outside of logic or mathematics to human language, treating it as a mathematical formal system with a formal grammar. [27]

A characteristic stance of formalist approaches is the primacy of form (like syntax), and the conception of language as a system in isolation from the outer world. An example of this is de Saussure's principle of arbitrariness of sign, according to which there is no intrinsic relationship between a signifier (a word) and the signified (concept) to which it refers. This is contrasted by the principle of iconicity, according to which a sign, like a word, can be influenced by its usage and by the concepts it refers to. The principle of iconicity is shared by functionalist approaches, like cognitive linguistics and usage-based linguistics, and also by linguistic typology. [28] [29]

Generative linguistics has been characterized, and parodied, as the view that a dictionary and a grammar textbook adequately describe a language. [30] The increasingly abstract way in which syntactic rules have been defined in generative approaches has been criticized by cognitive linguistics as having little regard for the cognitive reality of how language is actually represented in the human mind. [31] Another criticism is directed toward the principle of autonomy of syntax and encapsulation of the language system, pointing out that "structural aspects of language have been shaped by the functions it needs to perform," [31] [32] which is also an argument in favor of the opposite principle of iconicity.