In linguistics, syntax is the study of how words and morphemes combine to form larger units such as phrases and sentences. Central concerns of syntax include word order, grammatical relations, hierarchical sentence structure (constituency), agreement, the nature of crosslinguistic variation, and the relationship between form and meaning (semantics). There are numerous approaches to syntax that differ in their central assumptions and goals.

A syntactic category is a syntactic unit that theories of syntax assume. Word classes, largely corresponding to traditional parts of speech, are syntactic categories. In phrase structure grammars, the phrasal categories are also syntactic categories. Dependency grammars, however, do not acknowledge phrasal categories.

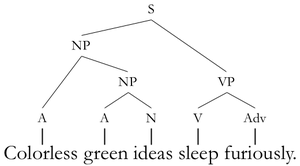

Phrase structure rules are a type of rewrite rule used to describe a given language's syntax and are closely associated with the early stages of transformational grammar, proposed by Noam Chomsky in 1957. They are used to break down a natural language sentence into its constituent parts, also known as syntactic categories, including both lexical categories and phrasal categories. A grammar that uses phrase structure rules is a type of phrase structure grammar. Phrase structure rules as they are commonly employed operate according to the constituency relation, and a grammar that employs phrase structure rules is therefore a constituency grammar; as such, it stands in contrast to dependency grammars, which are based on the dependency relation.

In linguistics, transformational grammar (TG) or transformational-generative grammar (TGG) is part of the theory of generative grammar, especially of natural languages. It considers grammar to be a system of rules that generate exactly those combinations of words that form grammatical sentences in a given language and involves the use of defined operations to produce new sentences from existing ones.

A noun phrase – or NP or nominal (phrase) – is a phrase that usually has a noun or pronoun as its head, and has the same grammatical functions as a noun. Noun phrases are very common cross-linguistically, and they may be the most frequently occurring phrase type.

A parse tree or parsing tree or derivation tree or concrete syntax tree is an ordered, rooted tree that represents the syntactic structure of a string according to some context-free grammar. The term parse tree itself is used primarily in computational linguistics; in theoretical syntax, the term syntax tree is more common.

In linguistics, X-bar theory is a model of phrase-structure grammar and a theory of syntactic category formation that was first proposed by Noam Chomsky in 1970 reformulating the ideas of Zellig Harris (1951), and further developed by Ray Jackendoff, along the lines of the theory of generative grammar put forth in the 1950s by Chomsky. It attempts to capture the structure of phrasal categories with a single uniform structure called the X-bar schema, basing itself on the assumption that any phrase in natural language is an XP that is headed by a given syntactic category X. It played a significant role in resolving issues that phrase structure rules had, representative of which is the proliferation of grammatical rules, which is against the thesis of generative grammar.

In linguistics, the minimalist program is a major line of inquiry that has been developing inside generative grammar since the early 1990s, starting with a 1993 paper by Noam Chomsky.

Theta roles are the names of the participant roles associated with a predicate: the predicate may be a verb, an adjective, a preposition, or a noun. If an object is in motion or in a steady state as the speakers perceives the state, or it is the topic of discussion, it is called a theme. The participant is usually said to be an argument of the predicate. In generative grammar, a theta role or θ-role is the formal device for representing syntactic argument structure—the number and type of noun phrases—required syntactically by a particular verb. For example, the verb put requires three arguments.

In linguistics, branching refers to the shape of the parse trees that represent the structure of sentences. Assuming that the language is being written or transcribed from left to right, parse trees that grow down and to the right are right-branching, and parse trees that grow down and to the left are left-branching. The direction of branching reflects the position of heads in phrases, and in this regard, right-branching structures are head-initial, whereas left-branching structures are head-final. English has both right-branching (head-initial) and left-branching (head-final) structures, although it is more right-branching than left-branching. Some languages such as Japanese and Turkish are almost fully left-branching (head-final). Some languages are mostly right-branching (head-initial).

The term phrase structure grammar was originally introduced by Noam Chomsky as the term for grammar studied previously by Emil Post and Axel Thue. Some authors, however, reserve the term for more restricted grammars in the Chomsky hierarchy: context-sensitive grammars or context-free grammars. In a broader sense, phrase structure grammars are also known as constituency grammars. The defining trait of phrase structure grammars is thus their adherence to the constituency relation, as opposed to the dependency relation of dependency grammars.

Principles and parameters is a framework within generative linguistics in which the syntax of a natural language is described in accordance with general principles and specific parameters that for particular languages are either turned on or off. For example, the position of heads in phrases is determined by a parameter. Whether a language is head-initial or head-final is regarded as a parameter which is either on or off for particular languages. Principles and parameters was largely formulated by the linguists Noam Chomsky and Howard Lasnik. Many linguists have worked within this framework, and for a period of time it was considered the dominant form of mainstream generative linguistics.

In linguistics, the projection principle is a stipulation proposed by Noam Chomsky as part of the phrase structure component of generative-transformational grammar. The projection principle is used in the derivation of phrases under the auspices of the principles and parameters theory.

In generative grammar and related approaches, the logical form (LF) of a linguistic expression is the variant of its syntactic structure which undergoes semantic interpretation. It is distinguished from phonetic form, the structure which corresponds to a sentence's pronunciation. These separate representations are postulated in order to explain the ways in which an expression's meaning can be partially independent of its pronunciation, e.g. scope ambiguities.

Biolinguistics can be defined as the study of biology and the evolution of language. It is highly interdisciplinary as it is related to various fields such as biology, linguistics, psychology, anthropology, mathematics, and neurolinguistics to explain the formation of language. It seeks to yield a framework by which we can understand the fundamentals of the faculty of language. This field was first introduced by Massimo Piattelli-Palmarini, professor of Linguistics and Cognitive Science at the University of Arizona. It was first introduced in 1971, at an international meeting at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

In certain theories of linguistics, thematic relations, also known as semantic roles, are the various roles that a noun phrase may play with respect to the action or state described by a governing verb, commonly the sentence's main verb. For example, in the sentence "Susan ate an apple", Susan is the doer of the eating, so she is an agent; an apple is the item that is eaten, so it is a patient.

Merge is one of the basic operations in the Minimalist Program, a leading approach to generative syntax, when two syntactic objects are combined to form a new syntactic unit. Merge also has the property of recursion in that it may be applied to its own output: the objects combined by Merge are either lexical items or sets that were themselves formed by Merge. This recursive property of Merge has been claimed to be a fundamental characteristic that distinguishes language from other cognitive faculties. As Noam Chomsky (1999) puts it, Merge is "an indispensable operation of a recursive system ... which takes two syntactic objects A and B and forms the new object G={A,B}" (p. 2).

Aspects of the Theory of Syntax is a book on linguistics written by American linguist Noam Chomsky, first published in 1965. In Aspects, Chomsky presented a deeper, more extensive reformulation of transformational generative grammar (TGG), a new kind of syntactic theory that he had introduced in the 1950s with the publication of his first book, Syntactic Structures. Aspects is widely considered to be the foundational document and a proper book-length articulation of Chomskyan theoretical framework of linguistics. It presented Chomsky's epistemological assumptions with a view to establishing linguistic theory-making as a formal discipline comparable to physical sciences, i.e. a domain of inquiry well-defined in its nature and scope. From a philosophical perspective, it directed mainstream linguistic research away from behaviorism, constructivism, empiricism and structuralism and towards mentalism, nativism, rationalism and generativism, respectively, taking as its main object of study the abstract, inner workings of the human mind related to language acquisition and production.

The lexicalist hypothesis is a hypothesis proposed by Noam Chomsky in which he claims that syntactic transformations only can operate on syntactic constituents. It says that the system of grammar that assembles words is separate and different from the system of grammar that assembles phrases out of words.

In formal syntax, a node is a point in a tree diagram or syntactic tree that can be assigned a syntactic category label.