Johann Arndt was a German Lutheran theologian who wrote several influential books of devotional Christianity. Although reflective of the period of Lutheran Orthodoxy, he is seen as a forerunner of Pietism, a movement within Lutheranism that gained strength in the late 17th century.

Pseudophilosophy is a term applied to a philosophical idea or system which does not meet an expected set of philosophical standards. There is no universally accepted set of standards, but there are similarities and some common ground.

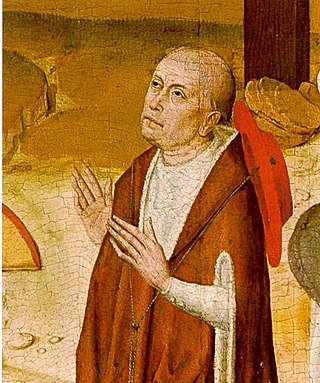

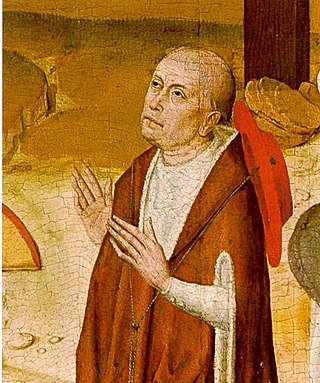

Nicholas of Cusa, also referred to as Nicholas of Kues and Nicolaus Cusanus, was a German Catholic cardinal and polymath active as a philosopher, theologian, jurist, mathematician and astronomer. One of the first German proponents of Renaissance humanism, he made spiritual and political contributions in European history. A notable example of this is his mystical or spiritual writings on "learned ignorance," as well as his participation in power struggles between Rome and the German states of the Holy Roman Empire.

Christian mysticism is the tradition of mystical practices and mystical theology within Christianity which "concerns the preparation [of the person] for, the consciousness of, and the effect of [...] a direct and transformative presence of God" or Divine love. Until the sixth century the practice of what is now called mysticism was referred to by the term contemplatio, c.q. theoria, from contemplatio, "looking at", "gazing at", "being aware of" God or the Divine. Christianity took up the use of both the Greek (theoria) and Latin terminology to describe various forms of prayer and the process of coming to know God.

Johannes Tauler OP was a German mystic, a Roman Catholic priest and a theologian. A disciple of Meister Eckhart, he belonged to the Dominican order. Tauler was known as one of the most important Rhineland mystics. He promoted a certain neo-platonist dimension in the Dominican spirituality of his time.

Henry Suso, OP was a German Dominican friar and the most popular vernacular writer of the fourteenth century. Suso is thought to have been born on 21 March 1295. An important author in both Latin and Middle High German, he is also notable for defending Meister Eckhart's legacy after Eckhart was posthumously condemned for heresy in 1329. He died in Ulm on 25 January 1366, and was beatified by the Catholic Church in 1831.

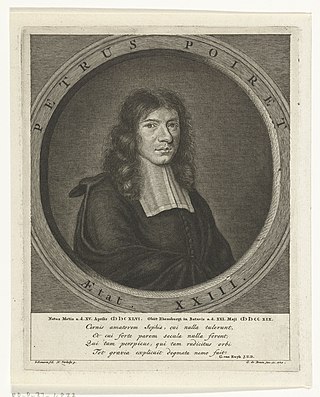

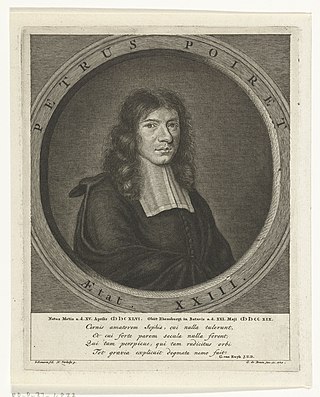

Pierre Poiret Naudé was a prominent French mystic and Christian philosopher. He was born in Metz and died in Rijnsburg.

Nicholas of Basel was a prominent member of the Beghard community, who travelled widely as a missionary and propagated the teachings of his sect.

Marguerite Porete was a Beguine, a French-speaking mystic and the author of The Mirror of Simple Souls, a work of Christian mysticism dealing with the workings of agape. She was burnt at the stake for heresy in Paris in 1310 after a lengthy trial, refusing to remove her book from circulation or recant her views.

Rulman Merswin was a German mystic, leader for a time of the Friends of God.

The Friend of God from the Oberland was the name of a figure in Middle Ages German mysticism, associated with the Friends of God and the conversion of Johannes Tauler. His name comes from the Bernese Oberland.

Theologia Germanica, also known as Theologia Deutsch or Teutsch, or as Der Franckforter, is a mystical treatise believed to have been written in the later 14th century by an anonymous author. According to the introduction of the Theologia the author was a priest and a member of the Teutonic Order living in Frankfurt, Germany.

The Brethren of the Free Spirit were adherents of a loose set of beliefs deemed heretical by the Catholic Church but held by some Christians, especially in the Low Countries, Germany, France, Bohemia, and Northern Italy between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries. The movement was first identified in the late thirteenth century. It was not a single movement or school of thought, and it caused great unease among Church leaders at the time. Adherents were also called Free Spirits.

The Sister Catherine Treatise is a work of Medieval Christian mysticism seen as representative of the Heresy of the Free Spirit of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries in Europe. Wrongly attributed to Christian mystic Meister Eckhart, it nevertheless shows the influence of his ideas or at least the ideas which he was accused or attributed as having had by the Inquisition.

The Mirror of Simple Souls is an early 14th-century work of Christian mysticism by Marguerite Porete dealing with the workings of Divine Love.

Love in this book layeth to souls the touches of his divine works privily hid under dark speech, so that they should taste the deeper draughts of his love and drink.

Henry of Nördlingen was a German Catholic priest from Bavaria, who lived in the 14th century, his date of death being unknown. He was the spiritual adviser of Margaretha Ebner, the mystic nun of Medingen.

Eckhart von Hochheim, commonly known as Meister Eckhart, Master Eckhart or Eckehart, claimed original name Johannes Eckhart, was a German Catholic theologian, philosopher and mystic, born near Gotha in the Landgraviate of Thuringia in the Holy Roman Empire.

John Everard (1584?–1641) was an English preacher and author. He was also a Familist, hermetic thinker, Neoplatonist, and alchemist. He is known for his translations of mystical and hermetic literature.

Horologium Sapientiae was written by the German Dominican Henry Suso between 1328 and 1330. The book belongs to the tradition of Rhineland mystics and German mysticism. It was quickly translated into a range of European languages and it was one of the three most popular European devotional texts of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.