In linguistics and related fields, pragmatics is the study of how context contributes to meaning. The field of study evaluates how human language is utilized in social interactions, as well as the relationship between the interpreter and the interpreted. Linguists who specialize in pragmatics are called pragmaticians. The field has been represented since 1986 by the International Pragmatics Association (IPrA).

In linguistics, deixis is the use of general words and phrases to refer to a specific time, place, or person in context, e.g., the words tomorrow, there, and they. Words are deictic if their semantic meaning is fixed but their denoted meaning varies depending on time and/or place. Words or phrases that require contextual information to be fully understood—for example, English pronouns—are deictic. Deixis is closely related to anaphora. Although this article deals primarily with deixis in spoken language, the concept is sometimes applied to written language, gestures, and communication media as well. In linguistic anthropology, deixis is treated as a particular subclass of the more general semiotic phenomenon of indexicality, a sign "pointing to" some aspect of its context of occurrence.

An interjection is a word or expression that occurs as an utterance on its own and expresses a spontaneous feeling or reaction. It is a diverse category, encompassing many different parts of speech, such as exclamations (ouch!, wow!), curses (damn!), greetings, response particles, hesitation markers, and other words. Due to its diverse nature, the category of interjections partly overlaps with a few other categories like profanities, discourse markers, and fillers. The use and linguistic discussion of interjections can be traced historically through the Greek and Latin Modistae over many centuries.

In pragmatics, a subdiscipline of linguistics, an implicature is something the speaker suggests or implies with an utterance, even though it is not literally expressed. Implicatures can aid in communicating more efficiently than by explicitly saying everything we want to communicate. The philosopher H. P. Grice coined the term in 1975. Grice distinguished conversational implicatures, which arise because speakers are expected to respect general rules of conversation, and conventional ones, which are tied to certain words such as "but" or "therefore". Take for example the following exchange:

Universal pragmatics (UP), more recently placed under the heading of formal pragmatics, is the philosophical study of the necessary conditions for reaching an understanding through communication. The philosopher Jürgen Habermas coined the term in his essay "What is Universal Pragmatics?" where he suggests that human competition, conflict, and strategic action are attempts to achieve understanding that have failed because of modal confusions. The implication is that coming to terms with how people understand or misunderstand one another could lead to a reduction of social conflict.

The concept of illocutionary acts was introduced into linguistics by the philosopher J. L. Austin in his investigation of the various aspects of speech acts. In his framework, locution is what was said and meant, illocution is what was done, and perlocution is what happened as a result.

In semiotics, linguistics, anthropology, and philosophy of language, indexicality is the phenomenon of a sign pointing to some element in the context in which it occurs. A sign that signifies indexically is called an index or, in philosophy, an indexical.

In linguistics, anaphora is the use of an expression whose interpretation depends upon another expression in context. In a narrower sense, anaphora is the use of an expression that depends specifically upon an antecedent expression and thus is contrasted with cataphora, which is the use of an expression that depends upon a postcedent expression. The anaphoric (referring) term is called an anaphor. For example, in the sentence Sally arrived, but nobody saw her, the pronoun her is an anaphor, referring back to the antecedent Sally. In the sentence Before her arrival, nobody saw Sally, the pronoun her refers forward to the postcedent Sally, so her is now a cataphor. Usually, an anaphoric expression is a pro-form or some other kind of deictic expression. Both anaphora and cataphora are species of endophora, referring to something mentioned elsewhere in a dialog or text.

In linguistics, focus is a grammatical category that conveys which part of the sentence contributes new, non-derivable, or contrastive information. In the English sentence "Mary only insulted BILL", focus is expressed prosodically by a pitch accent on "Bill" which identifies him as the only person Mary insulted. By contrast, in the sentence "Mary only INSULTED Bill", the verb "insult" is focused and thus expresses that Mary performed no other actions towards Bill. Focus is a cross-linguistic phenomenon and a major topic in linguistics. Research on focus spans numerous subfields including phonetics, syntax, semantics, pragmatics, and sociolinguistics.

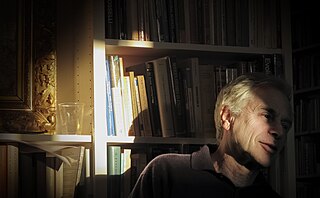

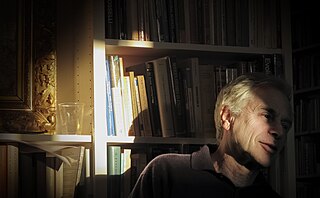

David Benjamin Kaplan is an American philosopher. He is the Hans Reichenbach Professor of Scientific Philosophy at the UCLA Department of Philosophy. His philosophical work focuses on the philosophy of language, logic, metaphysics, epistemology and the philosophy of Frege and Russell. He is best known for his work on demonstratives, propositions, and reference in intensional contexts. He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences in 1983 and a Corresponding Fellow of the British Academy in 2007.

In the branch of linguistics known as pragmatics, a presupposition is an implicit assumption about the world or background belief relating to an utterance whose truth is taken for granted in discourse. Examples of presuppositions include:

In linguistics and philosophy, modality refers to the ways language can express various relationships to reality or truth. For instance, a modal expression may convey that something is likely, desirable, or permissible. Quintessential modal expressions include modal auxiliaries such as "could", "should", or "must"; modal adverbs such as "possibly" or "necessarily"; and modal adjectives such as "conceivable" or "probable". However, modal components have been identified in the meanings of countless natural language expressions, including counterfactuals, propositional attitudes, evidentials, habituals, and generics.

In formal linguistics, discourse representation theory (DRT) is a framework for exploring meaning under a formal semantics approach. One of the main differences between DRT-style approaches and traditional Montagovian approaches is that DRT includes a level of abstract mental representations within its formalism, which gives it an intrinsic ability to handle meaning across sentence boundaries. DRT was created by Hans Kamp in 1981. A very similar theory was developed independently by Irene Heim in 1982, under the name of File Change Semantics (FCS). Discourse representation theories have been used to implement semantic parsers and natural language understanding systems.

Relevance theory is a framework for understanding the interpretation of utterances. It was first proposed by Dan Sperber and Deirdre Wilson, and is used within cognitive linguistics and pragmatics. The theory was originally inspired by the work of Paul Grice and developed out of his ideas, but has since become a pragmatic framework in its own right. The seminal book, Relevance, was first published in 1986 and revised in 1995.

In linguistics, a referring expression (RE) is any noun phrase, or surrogate for a noun phrase, whose function in discourse is to identify some individual object. The technical terminology for identify differs a great deal from one school of linguistics to another. The most widespread term is probably refer, and a thing identified is a referent, as for example in the work of John Lyons. In linguistics, the study of reference relations belongs to pragmatics, the study of language use, though it is also a matter of great interest to philosophers, especially those wishing to understand the nature of knowledge, perception and cognition more generally.

In linguistics, information structure, also called information packaging, describes the way in which information is formally packaged within a sentence. This generally includes only those aspects of information that “respond to the temporary state of the addressee’s mind”, and excludes other aspects of linguistic information such as references to background (encyclopedic/common) knowledge, choice of style, politeness, and so forth. For example, the difference between an active clause and a corresponding passive is a syntactic difference, but one motivated by information structuring considerations. Other structures motivated by information structure include preposing and inversion.

In linguistics and philosophy of language, an utterance is felicitous if it is pragmatically well-formed. An utterance can be infelicitous because it is self-contradictory, trivial, irrelevant, or because it is somehow inappropriate for the context of utterance. Researchers in semantics and pragmatics use felicity judgments much as syntacticians use grammaticality judgments. An infelicitous sentence is marked with the pound sign.

Logophoricity is a phenomenon of binding relation that may employ a morphologically different set of anaphoric forms, in the context where the referent is an entity whose speech, thoughts, or feelings are being reported. This entity may or may not be distant from the discourse, but the referent must reside in a clause external to the one in which the logophor resides. The specially-formed anaphors that are morphologically distinct from the typical pronouns of a language are known as logophoric pronouns, originally coined by the linguist Claude Hagège. The linguistic importance of logophoricity is its capability to do away with ambiguity as to who is being referred to. A crucial element of logophoricity is the logophoric context, defined as the environment where use of logophoric pronouns is possible. Several syntactic and semantic accounts have been suggested. While some languages may not be purely logophoric, logophoric context may still be found in those languages; in those cases, it is common to find that in the place where logophoric pronouns would typically occur, non-clause-bounded reflexive pronouns appear instead.

Explicature is a technical term in pragmatics, the branch of linguistics that concerns the meaning given to an utterance by its context. The explicatures of a sentence are what is explicitly said, often supplemented with contextual information. They contrast with implicatures, the information that the speaker conveys without actually stating it.

In linguistics and philosophy of language, the conversational scoreboard is a tuple which represents the discourse context at a given point in a conversation. The scoreboard is updated by each speech act performed by one of the interlocutors.