Ahmed II was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1691 to 1695.

Murad III was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1574 until his death in 1595. His rule saw battles with the Habsburgs and exhausting wars with the Safavids. The long-independent Morocco was for a time made a vassal of the empire but regained independence in 1582. His reign also saw the empire's expanding influence on the eastern coast of Africa. However, the empire was beset by increasing corruption and inflation from the New World which led to unrest among the Janissary and commoners. Relations with Elizabethan England were cemented during his reign as both had a common enemy in the Spanish. He was also a great patron of the arts, commissioning the Siyer-i-Nebi and other illustrated manuscripts.

Mehmed III was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1595 until his death in 1603. Mehmed was known for ordering the execution of his brothers and leading the army in the Long Turkish war, during which the Ottoman army was victorious at the decisive Battle of Keresztes. This victory was however undermined by some military losses such as in Gyor and Nikopol. He also ordered the successful quelling of the Jelali rebellions. The sultan also communicated with the court of Elizabeth I on the grounds of stronger commercial relations and in the hopes of England to ally with the Ottomans against the Spanish.

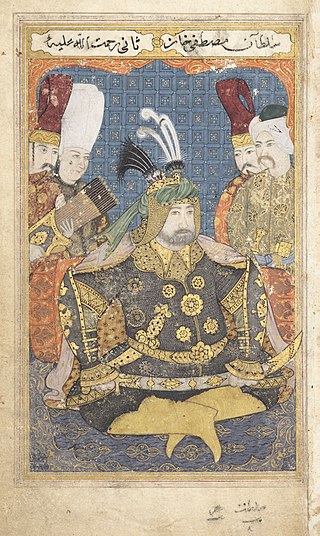

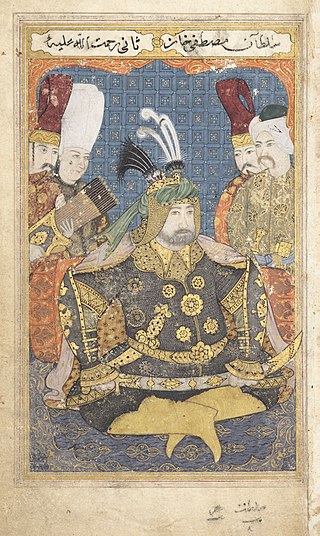

Mustafa II was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1695 to 1703.

Ibrahim was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1640 until 1648. He was born in Constantinople, the son of sultan Ahmed I by Kösem Sultan, an ethnic Greek originally named Anastasia.

Mehmed IV, also known as Mehmed the Hunter, was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1648 to 1687. He came to the throne at the age of six after his father was overthrown in a coup. Mehmed went on to become the second-longest-reigning sultan in Ottoman history after Suleiman the Magnificent. While the initial and final years of his reign were characterized by military defeat and political instability, during his middle years he oversaw the revival of the empire's fortunes associated with the Köprülü era. Mehmed IV was known by contemporaries as a particularly pious ruler, and was referred to as gazi, or "holy warrior" for his role in the many conquests carried out during his long reign.

Mahmud II was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1808 until his death in 1839. Often described as "Peter the Great of Turkey", Mahmud instituted extensive administrative, military, and fiscal reforms which culminated in the Decree of Tanzimat ("reorganization") that was carried out by his successors. His disbandment of the conservative Janissary corps removed a major obstacle to his and his successors' reforms in the Empire. Mahmud's reign was also marked by further Ottoman military defeat and loss of territory as a result of nationalist uprisings and European intervention.

The Ottoman dynasty consisted of the members of the imperial House of Osman, also known as the Ottomans. According to Ottoman tradition, the family originated from the Kayı tribe branch of the Oghuz Turks, under Osman I in northwestern Anatolia in the district of Bilecik, Söğüt. The Ottoman dynasty, named after Osman I, ruled the Ottoman Empire from c. 1299 to 1922.

Valide Sultan was the title held by the mother of a ruling sultan of the Ottoman Empire. The Ottomans first formally used the title in the 16th century as an epithet of Hafsa Sultan, mother of Sultan Suleyman I, superseding the previous epithets of Valide Hatun, mehd-i ulya. or "the nacre of the pearl of the sultanate". Normally, the living mother of a reigning sultan held this title. Those mothers who died before their sons' accession to the throne never received the title of valide sultan. In special cases sisters, grandmothers and stepmothers of a reigning sultan assumed the title and/or the functions valide sultan.

Turhan Hatice Sultan was the first Haseki Sultan of the Ottoman Sultan Ibrahim and Valide sultan as the mother of Mehmed IV. Turhan was prominent for the regency of her young son and her building patronage. She and Kösem Sultan are the only two women in Ottoman history to be regarded as official regents and had supreme control over the Ottoman Empire. As a result, Turhan became one of the prominent figures during the era known as Sultanate of Women.

Safiye Sultan was the Haseki Sultan of Murad III and Valide Sultan of the Ottoman Empire as the mother of Mehmed III and the grandmother of Sultans Ahmed I and Mustafa I. Safiye was also one of the eminent figures during the era known as the Sultanate of Women. She lived in the Ottoman Empire as a courtier during the reigns of seven sultans: Suleiman the Magnificent, Selim II, Murad III, Mehmed III, Ahmed I, Mustafa I and Osman II.

The Imperial Harem of the Ottoman Empire was the Ottoman sultan's harem – composed of the wives, servants, female relatives and the sultan's concubines – occupying a secluded portion (seraglio) of the Ottoman imperial household. This institution played an important social function within the Ottoman court, and wielded considerable political authority in Ottoman affairs, especially during the long period known as the Sultanate of Women.

Kösem Sultan, also known as Mahpeyker Sultan, was Haseki Sultan of the Ottoman Empire as the chief consort and legal wife of the Ottoman Sultan Ahmed I, Valide Sultan as the mother of sultans Murad IV and Ibrahim, and Büyük Valide Sultan as the grandmother of Sultan Mehmed IV. She became one of the most powerful and influential women in Ottoman history, as well as a central figure during the period known as the Sultanate of Women.

Hatice Sultan was an Ottoman princess, daughter of Sultan Selim I and Hafsa Sultan. She was the sister of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent.

Halime Sultan was a consort of Sultan Mehmed III, and the mother of Sultan Mustafa I. The first woman to be Valide Sultan twice and the only to be Valide twice of a same son. She had at least four children with Mehmed: two sons Şehzade Mahmud and Mustafa I, and two daughters, Hatice Sultan and Şah Sultan. She was de facto co-ruler as Valide Sultan from 22 November 1617 to 26 February 1618 and from 19 May 1622 to 10 September 1623, because her son was mentally instable. Halime was also one of the prominent figures during the era known as the Sultanate of Women.

The kizlar agha, formally the agha of the House of Felicity, was the head of the eunuchs who guarded the Ottoman Imperial Harem in Constantinople.

Akile Hatun, called also Akile Hanim, was a wife of Sultan Osman II of the Ottoman Empire.

The Imperial Council or Imperial Divan, was the de facto cabinet of the Ottoman Empire for most of its history. Initially an informal gathering of the senior ministers presided over by the Sultan in person, in the mid-15th century the Council's composition and function became firmly regulated. The Grand vizier, who became the Sultan's deputy as the head of government, assumed the role of chairing the Council, which comprised also the other viziers, charged with military and political affairs, the two kadi'askers or military judges, the defterdars in charge of finances, the nişancı in charge of the palace scribal service, and later the Kapudan Pasha, the head of the Ottoman Navy, and occasionally the beylerbey of Rumelia and the Agha of the Janissaries. The Council met in a dedicated building in the Second Courtyard of the Topkapi Palace, initially daily, then for four days a week by the 16th century. Its remit encompassed all matters of governance of the Empire, although the exact proceedings are no longer known. It was assisted by an extensive secretarial bureaucracy under the reis ül-küttab for the drafting of appropriate documents and the keeping of records. The Imperial Council remained the main executive organ of the Ottoman state until the mid-17th century, after which it lost most of its power to the office of the Grand Vizier. With the Tanzimat reforms of the early 19th century, it was eventually succeeded by a Western-style cabinet government.

The Sultanate of Women was a period when wives and mothers of the Sultans of the Ottoman Empire exerted extraordinary political influence.