The cerebral cortex, also known as the cerebral mantle, is the outer layer of neural tissue of the cerebrum of the brain in humans and other mammals. The cerebral cortex mostly consists of the six-layered neocortex, with just 10% consisting of the allocortex. It is separated into two cortices, by the longitudinal fissure that divides the cerebrum into the left and right cerebral hemispheres. The two hemispheres are joined beneath the cortex by the corpus callosum. The cerebral cortex is the largest site of neural integration in the central nervous system. It plays a key role in attention, perception, awareness, thought, memory, language, and consciousness. The cerebral cortex is part of the brain responsible for cognition.

The development of the nervous system, or neural development (neurodevelopment), refers to the processes that generate, shape, and reshape the nervous system of animals, from the earliest stages of embryonic development to adulthood. The field of neural development draws on both neuroscience and developmental biology to describe and provide insight into the cellular and molecular mechanisms by which complex nervous systems develop, from nematodes and fruit flies to mammals.

Lissencephaly is a set of rare brain disorders whereby the whole or parts of the surface of the brain appear smooth. It is caused by defective neuronal migration during the 12th to 24th weeks of gestation resulting in a lack of development of brain folds (gyri) and grooves (sulci). It is a form of cephalic disorder. Terms such as agyria and pachygyria are used to describe the appearance of the surface of the brain.

The neocortex, also called the neopallium, isocortex, or the six-layered cortex, is a set of layers of the mammalian cerebral cortex involved in higher-order brain functions such as sensory perception, cognition, generation of motor commands, spatial reasoning and language. The neocortex is further subdivided into the true isocortex and the proisocortex.

Polymicrogyria (PMG) is a condition that affects the development of the human brain by multiple small gyri (microgyri) creating excessive folding of the brain leading to an abnormally thick cortex. This abnormality can affect either one region of the brain or multiple regions.

In neuroanatomy, a gyrus is a ridge on the cerebral cortex. It is generally surrounded by one or more sulci. Gyri and sulci create the folded appearance of the brain in humans and other mammals.

Pachygyria is a congenital malformation of the cerebral hemisphere. It results in unusually thick convolutions of the cerebral cortex. Typically, children have developmental delay and seizures, the onset and severity depending on the severity of the cortical malformation. Infantile spasms are common in affected children, as is intractable epilepsy.

In neuroanatomy, a sulcus is a depression or groove in the cerebral cortex. It surrounds a gyrus, creating the characteristic folded appearance of the brain in humans and other mammals. The larger sulci are usually called fissures.

Radial glial cells, or radial glial progenitor cells (RGPs), are bipolar-shaped progenitor cells that are responsible for producing all of the neurons in the cerebral cortex. RGPs also produce certain lineages of glia, including astrocytes and oligodendrocytes. Their cell bodies (somata) reside in the embryonic ventricular zone, which lies next to the developing ventricular system.

There is much to be discovered about the evolution of the brain and the principles that govern it. While much has been discovered, not everything currently known is well understood. The evolution of the brain has appeared to exhibit diverging adaptations within taxonomic classes such as Mammalia and more vastly diverse adaptations across other taxonomic classes. Brain to body size scales allometrically. This means as body size changes, so do other physiological, anatomical, and biochemical constructs connecting the brain to the body. Small bodied mammals have relatively large brains compared to their bodies whereas large mammals have a smaller brain to body ratios. If brain weight is plotted against body weight for primates, the regression line of the sample points can indicate the brain power of a primate species. Lemurs for example fall below this line which means that for a primate of equivalent size, we would expect a larger brain size. Humans lie well above the line indicating that humans are more encephalized than lemurs. In fact, humans are more encephalized compared to all other primates. This means that human brains have exhibited a larger evolutionary increase in its complexity relative to its size. Some of these evolutionary changes have been found to be linked to multiple genetic factors, such as proteins and other organelles.

The ganglionic eminence (GE) is a transitory structure in the development of the nervous system that guides cell and axon migration. It is present in the embryonic and fetal stages of neural development found between the thalamus and caudate nucleus.

The Protomap is a primordial molecular map of the functional areas of the mammalian cerebral cortex during early embryonic development, at a stage when neural stem cells are still the dominant cell type. The protomap is a feature of the ventricular zone, which contains the principal cortical progenitor cells, known as radial glial cells. Through a process called 'cortical patterning', the protomap is patterned by a system of signaling centers in the embryo, which provide positional information and cell fate instructions. These early genetic instructions set in motion a development and maturation process that gives rise to the mature functional areas of the cortex, for example the visual, somatosensory, and motor areas. The term protomap was coined by Pasko Rakic. The protomap hypothesis was opposed by the protocortex hypothesis, which proposes that cortical proto-areas initially have the same potential, and that regionalization in large part is controlled by external influences, such as axonal inputs from the thalamus to the cortex. However, a series of papers in the year 2000 and in 2001 provided strong evidence against the protocortex hypothesis, and the protomap hypothesis has been well accepted since then. The protomap hypothesis, together with the related radial unit hypothesis, forms our core understanding of the embryonic development of the cerebral cortex. Once the basic structure is present and cortical neurons have migrated to their final destinations, many other processes contribute to the maturation of functional cortical circuits.

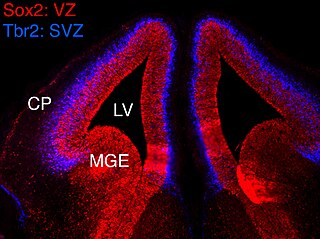

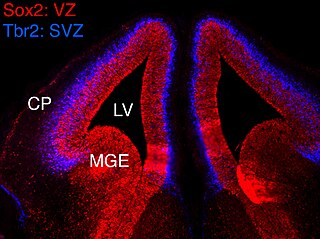

Eomesodermin also known as T-box brain protein 2 (Tbr2) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the EOMES gene.

The development of the cerebral cortex, known as corticogenesis is the process during which the cerebral cortex of the brain is formed as part of the development of the nervous system of mammals including its development in humans. The cortex is the outer layer of the brain and is composed of up to six layers. Neurons formed in the ventricular zone migrate to their final locations in one of the six layers of the cortex. The process occurs from embryonic day 10 to 17 in mice and between gestational weeks seven to 18 in humans.

In vertebrates, the ventricular zone (VZ) is a transient embryonic layer of tissue containing neural stem cells, principally radial glial cells, of the central nervous system (CNS). The VZ is so named because it lines the ventricular system, which contains cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The embryonic ventricular system contains growth factors and other nutrients needed for the proper function of neural stem cells. Neurogenesis, or the generation of neurons, occurs in the VZ during embryonic and fetal development as a function of the Notch pathway, and the newborn neurons must migrate substantial distances to their final destination in the developing brain or spinal cord where they will establish neural circuits. A secondary proliferative zone, the subventricular zone (SVZ), lies adjacent to the VZ. In the embryonic cerebral cortex, the SVZ contains intermediate neuronal progenitors that continue to divide into post-mitotic neurons. Through the process of neurogenesis, the parent neural stem cell pool is depleted and the VZ disappears. The balance between the rates of stem cell proliferation and neurogenesis changes during development, and species from mouse to human show large differences in the number of cell cycles, cell cycle length, and other parameters, which is thought to give rise to the large diversity in brain size and structure.

Neurogenesis is the process by which nervous system cells, the neurons, are produced by neural stem cells (NSCs). In short, it is brain growth in relation to its organization. This occurs in all species of animals except the porifera (sponges) and placozoans. Types of NSCs include neuroepithelial cells (NECs), radial glial cells (RGCs), basal progenitors (BPs), intermediate neuronal precursors (INPs), subventricular zone astrocytes, and subgranular zone radial astrocytes, among others.

The Radial Unit Hypothesis (RUH) is a conceptual theory of cerebral cortex development, first described by Pasko Rakic. The RUH states that the cerebral cortex develops during embryogenesis as an array of interacting cortical columns, or 'radial units', each of which originates from a transient stem cell layer called the ventricular zone, which contains neural stem cells known as radial glial cells.

TMF-regulated nuclear protein 1 is a nuclear protein that in humans is encoded by the TRNP1 gene. TRNP1 plays a crucial role in cellular proliferation and brain development. Trnp1 is the first protein that has been shown to play a major role in cortical folding. It represents a major stem cell factor, that is involved in crucial processes during brain but also stem cell development. Trnp1 controls gene expression levels and is sufficient to induce gyri and sulci in the developing brain. Local differences of Trnp1 expression levels in the human brain correlate with cortical folding.

Microlissencephaly (MLIS) is a rare congenital brain disorder that combines severe microcephaly with lissencephaly. Microlissencephaly is a heterogeneous disorder, i.e. it has many different causes and a variable clinical course. Microlissencephaly is a malformation of cortical development (MCD) that occurs due to failure of neuronal migration between the third and fifth month of gestation as well as stem cell population abnormalities. Numerous genes have been found to be associated with microlissencephaly, however, the pathophysiology is still not completely understood.

Intermediate progenitor cells (IPCs) are a type of progenitor cell in the developing cerebral cortex. They are multipolar cells produced by radial glial cells who have undergone asymmetric division. IPCs can produce neuron cells via neurogenesis and are responsible for ensuring the proper quantity of cortical neurons are produced. In mammals, neural stem cells are the primary progenitors during embryogenesis whereas intermediate progenitor cells are the secondary progenitors.