Inflammation of the geniculate ganglion of the facial nerve is a late consequence of varicella zoster virus (VZV) known as Ramsay Hunt syndrome (RHS), commonly known as herpes zoster oticus. In regards with the frequency, less than 1% of varicella zoster infections involve the facial nerve and result in RHS. It is traditionally defined as a triad of ipsilateral facial paralysis, otalgia, and vesicles close to the ear and auditory canal. Due to its proximity to the vestibulocochlear nerve, the virus can spread and cause hearing loss, tinnitus (hearing noises that are not causes by outside sounds), and vertigo. It is common for diagnoses to be overlooked or delayed, which can raise the likelihood of long-term consequences. It is more complicated than Bell's palsy. Therapy aims to shorten its overall length, while also providing pain relief and averting any consequences.

Botulinum toxin, or botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT), is a neurotoxic protein produced by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum and related species. It prevents the release of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine from axon endings at the neuromuscular junction, thus causing flaccid paralysis. The toxin causes the disease botulism. The toxin is also used commercially for medical and cosmetic purposes.

Bell's palsy is a type of facial paralysis that results in a temporary inability to control the facial muscles on the affected side of the face. In most cases, the weakness is temporary and significantly improves over weeks. Symptoms can vary from mild to severe. They may include muscle twitching, weakness, or total loss of the ability to move one or, in rare cases, both sides of the face. Other symptoms include drooping of the eyelid, a change in taste, and pain around the ear. Typically symptoms come on over 48 hours. Bell's palsy can trigger an increased sensitivity to sound known as hyperacusis.

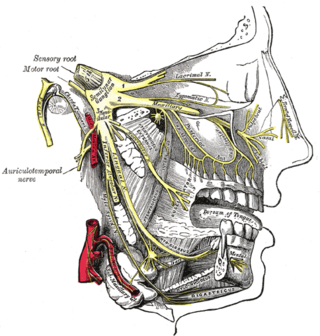

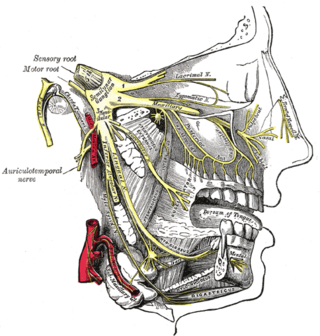

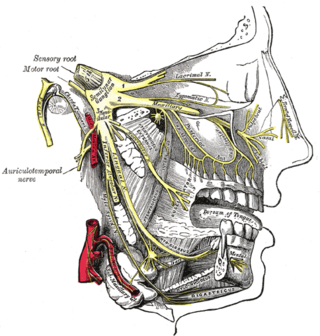

Trigeminal neuralgia, also called Fothergill disease, tic douloureux, or trifacial neuralgia is a long-term pain disorder that affects the trigeminal nerve, the nerve responsible for sensation in the face and motor functions such as biting and chewing. It is a form of neuropathic pain. There are two main types: typical and atypical trigeminal neuralgia. The typical form results in episodes of severe, sudden, shock-like pain in one side of the face that lasts for seconds to a few minutes. Groups of these episodes can occur over a few hours. The atypical form results in a constant burning pain that is less severe. Episodes may be triggered by any touch to the face. Both forms may occur in the same person. It is regarded as one of the most painful disorders known to medicine, and often results in depression.

Piriformis syndrome is a condition which is believed to result from compression of the sciatic nerve by the piriformis muscle. Symptoms may include pain and numbness in the buttocks and down the leg. Often symptoms are worsened with sitting or running.

Neuralgia is pain in the distribution of one or more nerves, as in intercostal neuralgia, trigeminal neuralgia, and glossopharyngeal neuralgia.

Occipital neuralgia (ON) is a painful condition affecting the posterior head in the distributions of the greater occipital nerve (GON), lesser occipital nerve (LON), third occipital nerve (TON), or a combination of the three. It is paroxysmal, lasting from seconds to minutes, and often consists of lancinating pain that directly results from the pathology of one of these nerves. It is paramount that physicians understand the differential diagnosis for this condition and specific diagnostic criteria. There are multiple treatment modalities, several of which have well-established efficacy in treating this condition.

Microvascular decompression (MVD), also known as the Jannetta procedure, is a neurosurgical procedure used to treat trigeminal neuralgia a pain syndrome characterized by severe episodes of intense facial pain, and hemifacial spasm. The procedure is also used experimentally to treat tinnitus and vertigo caused by vascular compression on the vestibulocochlear nerve.

Blepharospasm is any abnormal contraction of the orbicularis oculi muscle. The condition should be distinguished from the more common, and milder, involuntary quivering of an eyelid, known as myokymia, or fasciculation. In most cases, blepharospasm symptoms last for a few days and then disappear without treatment, but in some cases the twitching is chronic and persistent, causing life-long challenges. In these cases, the symptoms are often severe enough to result in functional blindness. The person's eyelids feel like they are clamping shut and will not open without great effort. People have normal eyes, but for periods of time are effectively blind due to their inability to open their eyelids. In contrast, the reflex blepharospasm is due to any pain in and around the eye.

Spasmodic torticollis is an extremely painful chronic neurological movement disorder causing the neck to involuntarily turn to the left, right, upwards, and/or downwards. The condition is also referred to as "cervical dystonia". Both agonist and antagonist muscles contract simultaneously during dystonic movement. Causes of the disorder are predominantly idiopathic. A small number of patients develop the disorder as a result of another disorder or disease. Most patients first experience symptoms midlife. The most common treatment for spasmodic torticollis is the use of botulinum toxin type A.

Meige's syndrome is a type of dystonia. It is also known as Brueghel's syndrome and oral facial dystonia. It is actually a combination of two forms of dystonia, blepharospasm and oromandibular dystonia (OMD).

Parry–Romberg syndrome (PRS) is a rare disease characterized by progressive shrinkage and degeneration of the tissues beneath the skin, usually on only one side of the face but occasionally extending to other parts of the body. An autoimmune mechanism is suspected, and the syndrome may be a variant of localized scleroderma, but the precise cause and pathogenesis of this acquired disorder remains unknown. It has been reported in the literature as a possible consequence of sympathectomy. The syndrome has a higher prevalence in females and typically appears between 5 and 15 years of age.

Spasmodic dysphonia, also known as laryngeal dystonia, is a disorder in which the muscles that generate a person's voice go into periods of spasm. This results in breaks or interruptions in the voice, often every few sentences, which can make a person difficult to understand. The person's voice may also sound strained or they may be nearly unable to speak. Onset is often gradual and the condition is lifelong.

Synkinesis is a neurological symptom in which a voluntary muscle movement causes the simultaneous involuntary contraction of other muscles. An example might be smiling inducing an involuntary contraction of the eye muscles, causing a person to squint when smiling. Facial and extraocular muscles are affected most often; in rare cases, a person's hands might perform mirror movements.

In medicine, an avulsion is an injury in which a body structure is torn off by either trauma or surgery. The term most commonly refers to a surface trauma where all layers of the skin have been torn away, exposing the underlying structures. This is similar to an abrasion but more severe, as body parts such as an eyelid or an ear can be partially or fully detached from the body.

Migraine surgery is a surgical operation undertaken with the goal of reducing or preventing migraines. Migraine surgery most often refers to surgical decompression of one or several nerves in the head and neck which have been shown to trigger migraine symptoms in many migraine sufferers. Following the development of nerve decompression techniques for the relief of migraine pain in the year 2000, these procedures have been extensively studied and shown to be effective in appropriate candidates. The nerves that are most often addressed in migraine surgery are found outside of the skull, in the face and neck, and include the supra-orbital and supra-trochlear nerves in the forehead, the zygomaticotemporal nerve and auriculotemporal nerves in the temple region, and the greater occipital, lesser occipital, and third occipital nerves in the back of the neck. Nerve impingement in the nasal cavity has additionally been shown to be a trigger of migraine symptoms.

Atypical trigeminal neuralgia (ATN), or type 2 trigeminal neuralgia, is a form of trigeminal neuralgia, a disorder of the fifth cranial nerve. This form of nerve pain is difficult to diagnose, as it is rare and the symptoms overlap with several other disorders. The symptoms can occur in addition to having migraine headache, or can be mistaken for migraine alone, or dental problems such as temporomandibular joint disorder or musculoskeletal issues. ATN can have a wide range of symptoms and the pain can fluctuate in intensity from mild aching to a crushing or burning sensation, and also to the extreme pain experienced with the more common trigeminal neuralgia.

Botulinum toxin therapy of strabismus is a medical technique used sometimes in the management of strabismus, in which botulinum toxin is injected into selected extraocular muscles in order to reduce the misalignment of the eyes. The injection of the toxin to treat strabismus, reported upon in 1981, is considered to be the first ever use of botulinum toxin for therapeutic purposes. Today, the injection of botulinum toxin into the muscles that surround the eyes is one of the available options in the management of strabismus. Other options for strabismus management are vision therapy and occlusion therapy, corrective glasses and prism glasses, and strabismus surgery.

The management of strabismus may include the use of drugs or surgery to correct the strabismus. Agents used include paralytic agents such as botox used on extraocular muscles, topical autonomic nervous system agents to alter the refractive index in the eyes, and agents that act in the central nervous system to correct amblyopia.

Alan Brown Scott was an American ophthalmologist specializing in eye muscles and their disorders, such as strabismus. He is best known for his work in developing and manufacturing the drug that became known as Botox, research described as "groundbreaking" by the ASCRS.