Gnosticism is a collection of religious ideas and systems that coalesced in the late 1st century AD among Jewish and early Christian sects. These various groups emphasized personal spiritual knowledge (gnosis) above the proto-orthodox teachings, traditions, and authority of religious institutions. Gnostic cosmogony generally presents a distinction between a supreme, hidden God and a malevolent lesser divinity who is responsible for creating the material universe. Consequently, Gnostics considered material existence flawed or evil, and held the principal element of salvation to be direct knowledge of the hidden divinity, attained via mystical or esoteric insight. Many Gnostic texts deal not in concepts of sin and repentance, but with illusion and enlightenment.

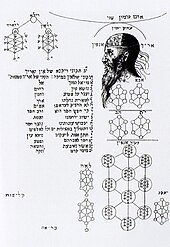

Kabbalah is an esoteric method, discipline and school of thought in Jewish mysticism. A traditional Kabbalist is called a Mekubbal. The definition of Kabbalah varies according to the tradition and aims of those following it, from its origin in medieval Judaism to its later adaptations in Western esotericism. Jewish Kabbalah is a set of esoteric teachings meant to explain the relationship between the unchanging, eternal God—the mysterious Ein Sof —and the mortal, finite universe. It forms the foundation of mystical religious interpretations within Judaism.

The Sophia of Jesus Christ is a Gnostic text that was first discovered in the Berlin Codex. More famously, the Sophia of Jesus Christ is also among the many Gnostic tractates in the Nag Hammadi codices, discovered in Egypt in 1945. The Berlin-Codex manuscript probably dates to c. AD 400, and the Nag-Hammadi manuscript has been dated to the 300s. However, these are complemented by a few fragments in Greek dating from the 200s, indicating an earlier date for the contents.

Hermes Trismegistus is a legendary Hellenistic period figure that originated as a syncretic combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth. He is the purported author of the Hermetica, a widely diverse series of ancient and medieval pseudepigraphica that lay the basis of various philosophical systems known as Hermeticism.

Jewish philosophy includes all philosophy carried out by Jews, or in relation to the religion of Judaism. Until modern Haskalah and Jewish emancipation, Jewish philosophy was preoccupied with attempts to reconcile coherent new ideas into the tradition of Rabbinic Judaism, thus organizing emergent ideas that are not necessarily Jewish into a uniquely Jewish scholastic framework and world-view. With their acceptance into modern society, Jews with secular educations embraced or developed entirely new philosophies to meet the demands of the world in which they now found themselves.

Hermeticism or Hermetism is a philosophical and religious system based on the purported teachings of Hermes Trismegistus. These teachings are contained in the various writings attributed to Hermes, which were produced over a period spanning many centuries and may be very different in content and scope.

The Hermetica are texts attributed to the legendary Hellenistic figure Hermes Trismegistus, a syncretic combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth. These texts may vary widely in content and purpose, but are usually subdivided into two main categories, the "technical" and "religio-philosophical" Hermetica.

The Corpus Hermeticum is a collection of 17 Greek writings whose authorship is traditionally attributed to the legendary Hellenistic figure Hermes Trismegistus, a syncretic combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth. The treatises were originally written between c. 100 and c. 300 CE, but the collection as known today was first compiled by medieval Byzantine editors. It was translated into Latin in the 15th century by the Italian humanist scholars Marsilio Ficino (1433–1499) and Lodovico Lazzarelli (1447–1500).

The Gospel of the Hebrews, or Gospel according to the Hebrews, is a lost Jewish–Christian gospel. The text of the gospel is lost, with only fragments of it surviving as brief quotations by the early Church Fathers and in apocryphal writings. The fragments contain traditions of Jesus' pre-existence, incarnation, baptism, and probably of his temptation, along with some of his sayings. Distinctive features include a Christology characterized by the belief that the Holy Spirit is Jesus' Divine Mother and a first resurrection appearance to James, the brother of Jesus, showing a high regard for James as the leader of the Jewish Christian church in Jerusalem. It was probably composed in Greek in the first decades of the 2nd century, and is believed to have been used by Greek-speaking Jewish Christians in Egypt during that century.

Academic study of Jewish mysticism, especially since Gershom Scholem's Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism (1941), draws distinctions between different forms of mysticism which were practiced in different eras of Jewish history. Of these, Kabbalah, which emerged in 12th-century southwestern Europe, is the most well known, but it is not the only typological form, nor was it the first form which emerged. Among the previous forms were Merkabah mysticism, and Ashkenazi Hasidim around the time of the emergence of Kabbalah.

Isaac ben Judah Abarbanel, commonly referred to as Abarbanel, also spelled Abravanel, Avravanel, or Abrabanel, was a Portuguese Jewish statesman, philosopher, Bible commentator, and financier.

Hermetic or related forms may refer to:

The Sethians were one of the main currents of Gnosticism during the 2nd and 3rd century CE, along with Valentinianism and Basilideanism. According to John D. Turner, it originated in the 2nd century CE as a fusion of two distinct Hellenistic Judaic philosophies and was influenced by Christianity and Middle Platonism. However, the exact origin of Sethianism is not properly understood.

Norea is a figure in Gnostic cosmology. She plays a prominent role in two surviving texts from the Nag Hammadi library. In Hypostasis of the Archons, she is the daughter of Adam and Eve and sister of Seth. She sets fire to Noah's Ark and receives a divine revelation from the Luminary Eleleth. In Thought of Norea, she "extends into prehistory" as "she assumes the features here of the fallen Sophia." In Mandean literature, she is instead identified as the wife of either Noah or Shem. She is also sometimes said to be the syzygy of Adam.

Elia del Medigo, also called Elijah Delmedigo or Elias ben Moise del Medigo and sometimes known to his contemporaries as Helias Hebreus Cretensis or in Hebrew Elijah Mi-Qandia. According to Jacob Joshua Ross, "while the non-Jewish students of Delmedigo may have classified him as an “Averroist”, he clearly saw himself as a follower of Maimonides". But, according to other scholars, Delmedigo was clearly a strong follower of Averroes' doctrines, even the more radical ones: unity of intellect, eternity of the world, autonomy of reason from the boundaries of revealed religion.

Wouter Jacobus Hanegraaff is professor of the History of Hermetic Philosophy and related currents at the University of Amsterdam, Netherlands. He served as the first president of the European Society for the Study of Western Esotericism (ESSWE) from 2005 to 2013.

Ludovico Lazzarelli was an Italian poet, philosopher, courtier, hermeticist and (likely) magician and diviner of the early Renaissance.

The Hypostasis of the Archons, also called The Reality of the Rulers or The Nature of the Rulers, is a Gnostic writing. The only known surviving manuscript is in Coptic as the fourth tractate in Codex II of the Nag Hammadi library. It has some similarities with On the Origin of the World, which immediately follows it in the codex. The Coptic version is a translation of a Greek original, possibly written in Egypt in the third century AD. The text begins as an exegesis on Genesis 1–6 and concludes as a discourse explaining the nature of the world's evil authorities. It applies Christian Gnostic beliefs to the Jewish origin story, and translator Bentley Layton believes the intent is anti-Jewish.

Hermetic Qabalah is a Western esoteric tradition involving mysticism and the occult. It is the underlying philosophy and framework for magical societies such as the Golden Dawn, Thelemic orders, mystical-religious societies such as the Builders of the Adytum and the Fellowship of the Rosy Cross, and is a precursor to the Neopagan, Wiccan and New Age movements. The Hermetic Qabalah is the basis for Qliphothic Qabala as studied by left-hand path orders, such as the Typhonian Order.

The Definitions of Hermes Trismegistus to Asclepius is a collection of aphorisms attributed to the legendary Hellenistic figure Hermes Trismegistus, most likely dating to the first century CE.