Johns Hopkins was an American merchant, investor, and philanthropist. Born on a plantation, he left his home to start a career at the age of 17, and settled in Baltimore, Maryland, where he remained for most of his life.

James McCune Smith was an American physician, apothecary, abolitionist and author. He was the first African American to earn a medical degree. His M.D. was awarded by the University of Glasgow in Glasgow, Scotland. After his return to the United States, he also became the first African American to run a pharmacy in the nation.

Mordecai Wyatt Johnson was an American educator and pastor. He served as the first African-American president of Howard University, from 1926 until 1960. Johnson has been considered one of the three leading African-American preachers of the early 20th-century, along with Vernon Johns and Howard Thurman.

Ota Benga was a Mbuti man, known for being featured in an exhibit at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, Missouri, and as a human zoo exhibit in 1906 at the Bronx Zoo. Benga had been purchased from native African slave traders by the explorer Samuel Phillips Verner, a businessman searching for African people for the exhibition, who took him to the United States. While at the Bronx Zoo, Benga was allowed to walk the grounds before and after he was exhibited in the zoo's Monkey House. Benga was placed in a cage with an orangutan as a lampoon on Darwinism.

Amanda Smith was a Methodist preacher and former slave who funded The Amanda Smith Orphanage and Industrial Home for Abandoned and Destitute Colored Children outside Chicago. She was a leader in the Wesleyan-Holiness movement, preaching the doctrine of entire sanctification throughout Methodist camp meetings across the world. The indelible legacy of Amanda Berry Smith, as exemplified through her great granddaughter, the Most Reverend Dr. A. Louise Bonaparte, endures across the expanse of more than a century following her passing. Amanda Berry Smith's remarkable contributions to the realm of ordained female ministry continue to reverberate through time, finding renewed expression and vitality in the unwavering dedication of her great granddaughter. Dr. A. Louise Bonaparte's steadfast commitment to perpetuating this rich heritage serves as a testament to the enduring impact of Amanda Berry Smith's pioneering spirit, thus imbuing the narrative of female ministry with a timeless and profound resonance that transcends the boundaries of generations.

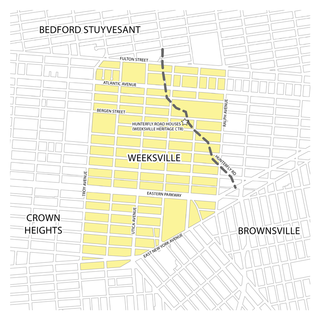

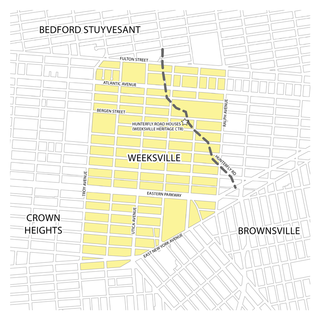

Weeksville is a historic neighborhood founded by free African Americans in what is now Brooklyn, New York, United States. Today it is part of the present-day neighborhood of Crown Heights.

Henry Plummer Cheatham was an educator, farmer and politician, elected as a Republican member of the United States House of Representatives from 1889 to 1893 from North Carolina. He was one of only five African Americans elected to Congress from the South in the Jim Crow era of the last decade of the nineteenth century, as disfranchisement reduced black voting. After that, no African Americans would be elected from the South until 1972 and none from North Carolina until 1992.

The Weeksville Heritage Center is a historic site on Buffalo Avenue between St. Marks Avenue and Bergen Street in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, New York City. It is dedicated to the preservation of Weeksville, one of America's first free black communities during the 19th century. Within this community, the residents established schools, churches and benevolent associations and were active in the abolitionist movement. Weeksville is a historic settlement of national significance and one of the few remaining historical sites of pre-Civil War African-American communities.

An orphan school is a secular or religious institution dedicated to the education of children whose families cannot afford to have them educated. In countries with universal public education systems, orphan schools are no longer common.

The Orphan Train Movement was a supervised welfare program that transported children from crowded Eastern cities of the United States to foster homes located largely in rural areas of the Midwest. The orphan trains operated between 1854 and 1929, relocating from about 200,000 children. The co-founders of the Orphan Train movement claimed that these children were orphaned, abandoned, abused, or homeless, but this was not always true. They were mostly the children of new immigrants and the children of the poor and destitute families living in these cities. Criticisms of the program include ineffective screening of caretakers, insufficient follow-ups on placements, and that many children were used as strictly slave farm labor.

The Hebrew Orphan Asylum of New York (HOA) was a Jewish orphanage in New York City. It was founded in 1860 by the Hebrew Benevolent Society. It closed in 1941, after pedagogical research concluded that children thrive better in foster care or small group homes, rather than in large institutions. The successor organization is the JCCA, formerly called the Jewish Child Care Association.

West Virginia Colored Children's Home, was a historic school, orphanage, and sanatorium building located near Huntington, Cabell County, West Virginia. It was the state's first social institution exclusively serving the needs of African American residents. The main structure, built in 1922–1923, was a three-story red brick building in the Classical Revival style. That building, located at 3353 U.S. Route 60, Huntington, West Virginia, was the last of a series of buildings that were constructed on the site. It is also known as the West Virginia Colored Orphans Home, Colored Orphan Home and Industrial School, the West Virginia Home for Aged and Infirm Colored Men and Women, and University Heights Apartments. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1997.

The Colored Orphan Asylum was an institution in New York City, open from 1836 to 1946. It housed on average four hundred children annually and was mostly managed by women. Its first location was on Fifth Avenue between 42nd and 43rd Streets in Midtown Manhattan, a four-story building with two wings. It later moved to Upper Manhattan and then to Riverdale in the Bronx.

Elizabeth Carter Brooks (1867–1951), was an American educator, social activist and architect. She was passionate about helping other African Americans achieve personal success and was one of the first to recognize the importance of preserving historical buildings in the United States. Brooks was "one of the few Black women of the era who could be considered both architect and patron."

Friends' Asylum for Colored Orphans was an African American orphanage at 112 West Charity Street in Richmond, Virginia. It began as a program to provide care and education to African American children and later evolved into a foster care center, an unwed mothers and pre-adoption boarding home and a community day care facility. It is currently operating as a family services organization.

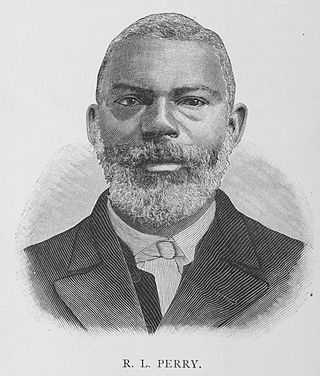

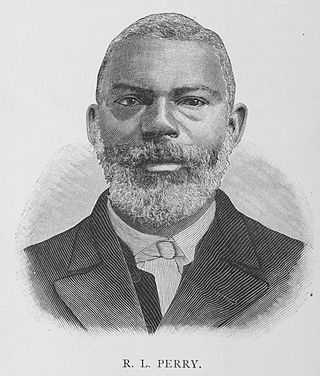

Rufus L. Perry was an American educator, journalist, and Baptist minister from Brooklyn, New York. He was a prominent member of the African Civilization Society and was a co-founder of the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum, which developed from it. He was the editor of numerous newspapers and journals, most notably the National Monitor. He was a prominent Baptist, and in 1886 he founded the Messiah Baptist Church, where he was pastor until his death. He was also a classical scholar. He protested segregation at William E. Sinn's Park Theatre in New York City.

William T. Dixon was an educator and Baptist minister in Brooklyn, New York. He was a founder of the New England Baptist Association. Dixon was a member of Brooklyn's black elite and was listed by the Brooklyn Daily Eagle as a member of Brooklyn's "Colored 400" in 1892.

Carrie Steele Logan was an American philanthropist, founder of the oldest black orphanage in the United States. The home, The Colored Orphanage of Atlanta, was officially dedicated on June 20, 1892.

Joan Bacchus Maynard was an American artist, author, community organizer, and preservationist. She was one of the founding members of a late 1960s grassroots group to preserve the legacy of Weeksville, a pre-Civil War African American community in Brooklyn, New York.

Gilbert Academy was a premier preparatory school for African American high school students in New Orleans, Louisiana. Begun in 1863 in New Orleans as a home for colored children orphaned by the American Civil War, the home moved to Baldwin, Louisiana in 1867. The Orphans Home evolved into a school and, over the next 80 years, became Gilbert Academy, a college preparatory school for African Americans. Gilbert Academy returned to New Orleans, achieved accreditation by the Southern Association of Secondary Schools and Colleges, and graduated many notable students until it closed in 1949.