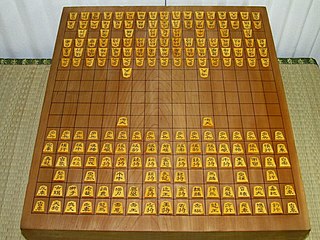

Shogi, also known as Japanese chess, is a strategy board game for two players. It is one of the most popular board games in Japan and is in the same family of games as Western chess, chaturanga, xiangqi, Indian chess, and janggi. Shōgi means general's board game.

Bughouse chess is a popular chess variant played on two chessboards by four players in teams of two. Normal chess rules apply, except that captured pieces on one board are passed on to the teammate on the other board, who then has the option of putting these pieces on their board.

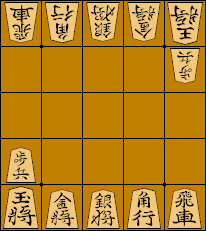

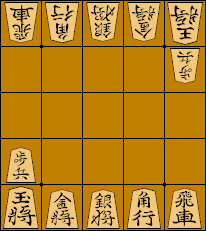

Minishogi is a modern variant of shogi. The game was invented around 1970 by Shigenobu Kusumoto of Osaka, Japan. The rules are nearly identical to those of standard shogi, with the exception that it is played on a 5x5 board with a reduced number of pieces, and each player's promotion zone consists only of the rank farthest from the player.

Combinatorial game theory measures game complexity in several ways:

- State-space complexity,

- Game tree size,

- Decision complexity,

- Game-tree complexity,

- Computational complexity.

Crazyhouse is a chess variant in which captured enemy pieces can be reintroduced, or dropped, into the game as one's own. It was derived as a two-player, single-board variant of bughouse chess.

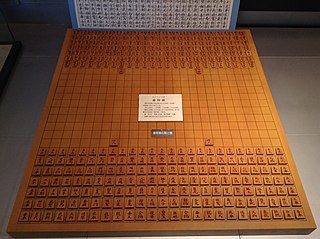

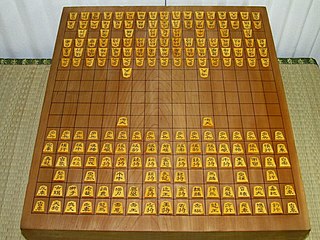

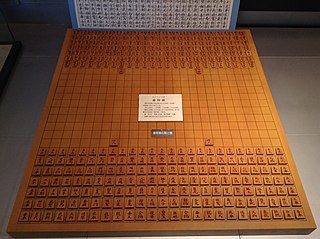

Tai shogi is a large-board variant of shogi. The game dates to the 15th century and is based on earlier large-board shogi games. Before the discovery of taikyoku shogi in 1997, tai shogi was believed to be the largest playable chess variant, if not board game, ever. One game may be played over several long sessions and require each player to make over a thousand moves. It was never a popular game; indeed, a single production of six game sets in the early 17th century was a notable event.

Yari shogi is a modern variant of shogi ; however, it is not Japanese. It was invented in 1981 by Christian Freeling of the Netherlands. This game accentuates shogi’s intrinsically forward range of direction by giving most of the pieces the ability to move any number of free squares orthogonally forward like a shogi lance. The opposite is true of promoted pieces which can move backward with the same power.

Tsume shogi or tsume (詰め) is the Japanese term for a shogi miniature problem in which the goal is to checkmate the opponent's king. Tsume problems usually present a situation that might occur in a shogi game, and the solver must find out how to achieve checkmate. It is similar to a mate-in-n chess problem.

Dai shogi or Kamakura dai shogi (鎌倉大将棋) is a chess variant native to Japan. It derived from Heian era shogi, and is similar to standard shogi in its rules and game play. Dai shogi is only one of several large board shogi variants. Its name means large shogi, from a time when there were three sizes of shogi games. Early versions of dai shogi can be traced back to the Kamakura period, from about AD 1230. It was the historical basis for the later, much more popular variant chu shogi.

Dai dai shōgi is a large board variant of shogi. The game dates back to the 15th century and is based on the earlier dai shogi. Apart from its size, the major difference is in the range of the pieces and the "promotion by capture" rule. It is the smallest board variant to use this rule.

Yonin shōgi,, is a four-person variant of shogi. It may be played with a dedicated yonin shogi set or with two sets of standard shogi pieces, and is played on a standard sized shogi board.

Sannin shōgi, or in full kokusai sannin shōgi, is a three-person shogi variant invented circa 1930 by Tanigasaki Jisuke and recently revived. It is played on a hexagonal grid of border length 7 with 127 cells. Standard shogi pieces may be used, and the rules for capture, promotion, drops, etc. are mostly similar to standard shogi. While piece movement differs somewhat from standard shogi, especially in the case of the powerful promoted king, the main difference in play is due to the rules for voluntary and mandatory alliance between two of the three players.

Three-player chess is a family of chess variants specially designed for three players. Many variations of three-player chess have been devised. They usually use a non-standard board, for example, a hexagonal or three-sided board that connects the center cells in a special way. The three armies are differentiated usually by color.

Zillions of Games is a commercial general game playing system developed by Jeff Mallett and Mark Lefler in 1998. The game rules are specified with S-expressions, Zillions rule language. It was designed to handle mostly abstract strategy board games or puzzles. After parsing the rules of the game, the system's artificial intelligence can automatically play one or more players. It treats puzzles as solitaire games and its AI can be used to solve them.

Shogi, like western chess, can be divided into the opening, middle game and endgame, each requiring a different strategy. The opening consists of arranging one's defenses and positioning for attack, the middle game consists of attempting to break through the opposing defenses while maintaining one's own, and the endgame starts when one side's defenses have been compromised.

Dōbutsu shōgi is a small shogi variant for young children. It was invented by women's professional shogi player Madoka Kitao, partially to attract young girls to the game. It is played on a 3×4 board and generally follows the rules of standard shogi, including drops, except that pieces can only move one square at a time, and the king reaching the enemy camp as an additional way to win the game.

Solving chess consists of finding an optimal strategy for the game of chess; that is, one by which one of the players can always force a victory, or either can force a draw. It is also related to more generally solving chess-like games such as Capablanca chess and infinite chess.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to chess:

Joel David Hamkins is an American mathematician and philosopher who is O'Hara Professor of Philosophy and Mathematics at the University of Notre Dame. He has made contributions in mathematical and philosophical logic, set theory and philosophy of set theory, in computability theory, and in group theory.