Related Research Articles

Stephen D. Krashen is an American linguist, educational researcher and activist, who is Emeritus Professor of Education at the University of Southern California. He moved from the linguistics department to the faculty of the School of Education in 1994.

A second language (L2) is a language spoken in addition to one's first language (L1). A second language may be a neighbouring language, another language of the speaker's home country, or a foreign language. A speaker's dominant language, which is the language a speaker uses most or is most comfortable with, is not necessarily the speaker's first language. For example, the Canadian census defines first language for its purposes as "the first language learned in childhood and still spoken", recognizing that for some, the earliest language may be lost, a process known as language attrition. This can happen when young children start school or move to a new language environment.

TPR Storytelling is a method of teaching foreign languages. TPRS lessons use a mixture of reading and storytelling to help students learn a foreign language in a classroom setting. The method works in three steps: in step one the new vocabulary structures to be learned are taught using a combination of translation, gestures, and personalized questions; in step two those structures are used in a spoken class story; and finally, in step three, these same structures are used in a class reading. Throughout these three steps, the teacher will use a number of techniques to help make the target language comprehensible to the students, including careful limiting of vocabulary, constant asking of easy comprehension questions, frequent comprehension checks, and very short grammar explanations known as "pop-up grammar". Many teachers also assign additional reading activities such as free voluntary reading, and there have been several easy novels written by TPRS teachers for this purpose.

Rod Ellis is a Kenneth W. Mildenberger Prize-winning British linguist. He is currently a research professor in the School of Education, at Curtin University in Perth, Australia. He is also a professor at Anaheim University, where he serves as the Vice president of academic affairs. Ellis is a visiting professor at Shanghai International Studies University as part of China’s Chang Jiang Scholars Program and an emeritus professor of the University of Auckland. He has also been elected as a fellow of the Royal Society of New Zealand.

Second-language acquisition (SLA), sometimes called second-language learning—otherwise referred to as L2acquisition, is the process by which people learn a second language. Second-language acquisition is also the scientific discipline devoted to studying that process. The field of second-language acquisition is regarded by some but not everybody as a sub-discipline of applied linguistics but also receives research attention from a variety of other disciplines, such as psychology and education.

Sequential bilingualism occurs when a person becomes bilingual by first learning one language and then another. The process is contrasted with simultaneous bilingualism, in which both languages are learned at the same time.

Task-based language teaching (TBLT), also known as task-based instruction (TBI), focuses on the use of authentic language to complete meaningful tasks in the target language. Such tasks can include visiting a doctor, conducting an interview, or calling customer service for help. Assessment is primarily based on task outcome rather than on accuracy of prescribed language forms. This makes TBLT especially popular for developing target language fluency and student confidence. As such, TBLT can be considered a branch of communicative language teaching (CLT).

The comprehension approach to language learning emphasizes understanding of language rather than speaking it. This is in contrast to the better-known communicative approach, under which learning is thought to emerge through language production, i.e. a focus on speech and writing.

Language teaching, like other educational activities, may employ specialized vocabulary and word use. This list is a glossary for English language learning and teaching using the communicative approach.

In the field of second language acquisition, there are many theories about the most effective way for language learners to acquire new language forms. One theory of language acquisition is the comprehensible output hypothesis.

The input hypothesis, also known as the monitor model, is a group of five hypotheses of second-language acquisition developed by the linguist Stephen Krashen in the 1970s and 1980s. Krashen originally formulated the input hypothesis as just one of the five hypotheses, but over time the term has come to refer to the five hypotheses as a group. The hypotheses are the input hypothesis, the acquisition–learning hypothesis, the monitor hypothesis, the natural order hypothesis and the affective filter hypothesis. The input hypothesis was first published in 1977.

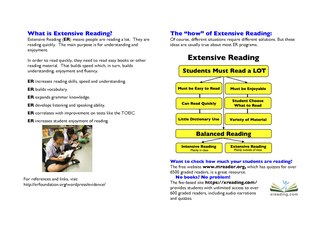

Extensive reading (ER) is the process of reading longer, easier texts for an extended period of time without a breakdown of comprehension, feeling overwhelmed, or the need to take breaks. It stands in contrast to intensive or academic reading, which is focused on a close reading of dense, shorter texts, typically not read for pleasure. Though used as a teaching strategy to promote second-language development, ER also applies to free voluntary reading and recreational reading both in and out of the classroom. ER is based on the assumption that we learn to read by reading.

The noticing hypothesis is a theory within second-language acquisition that a learner cannot continue advancing their language abilities or grasp linguistic features unless they consciously notice the input. The theory was proposed by Richard Schmidt in 1990.

The main purpose of theories of second-language acquisition (SLA) is to shed light on how people who already know one language learn a second language. The field of second-language acquisition involves various contributions, such as linguistics, sociolinguistics, psychology, cognitive science, neuroscience, and education. These multiple fields in second-language acquisition can be grouped as four major research strands: (a) linguistic dimensions of SLA, (b) cognitive dimensions of SLA, (c) socio-cultural dimensions of SLA, and (d) instructional dimensions of SLA. While the orientation of each research strand is distinct, they are in common in that they can guide us to find helpful condition to facilitate successful language learning. Acknowledging the contributions of each perspective and the interdisciplinarity between each field, more and more second language researchers are now trying to have a bigger lens on examining the complexities of second language acquisition.

Focus on form (FonF), also called form-focused instruction, is an approach to language education in which learners are made aware of linguistic forms – such as individual words and conjugations – in the context of a communicative activity. It is contrasted with focus on forms, in which forms are studied in isolation, and focus on meaning, in which no attention is paid to forms at all. For instruction to qualify as focus on form and not as focus on forms, the learner must be aware of the meaning and use of the language features before the form is brought to their attention. Focus on form was proposed by Michael Long in 1988.

The interface position is a concept in second language acquisition that describes the various possible theoretical relationships between implicit and explicit knowledge in the mind of a second language learner. Tacit knowledge is language knowledge that learners possess intuitively but are not able to put into words; explicit knowledge is language knowledge that learners possess and are also able to verbalize. For example, native speakers of Spanish intuitively know how to conjugate verbs, but may be unable to articulate how these grammatical rules work. Conversely, a non-native student of Spanish may be able to explain how Spanish verbs are conjugated, but may not yet be able to use these verbs in naturalistic, fluent speech. The nature of the relationship between these two types of knowledge in second language learners has received considerable attention in second language acquisition research.

The natural approach is a method of language teaching developed by Stephen Krashen and Tracy Terrell in the late 1970s and early 1980s. It aims to foster naturalistic language acquisition in a classroom setting, and to this end it emphasizes communication, and places decreased importance on conscious grammar study and explicit correction of student errors. Efforts are also made to make the learning environment as stress-free as possible. In the natural approach, language output is not forced, but allowed to emerge spontaneously after students have attended to large amounts of comprehensible language input.

Merrill Swain is a Canadian applied linguist whose research has focused on second language acquisition (SLA). Some of her most notable contributions to SLA research include the Output Hypothesis and her research related to immersion education. Swain is a Professor Emerita at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE) at the University of Toronto. Swain is also known for her work with Michael Canale on communicative competence. Swain was the president of the American Association for Applied Linguistics in 1998. She received her PhD in psychology at the University of California. Swain has co-supervised 64 PhD students.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to second-language acquisition:

Alison Mackey is a linguist who specializes in applied linguistics, second language acquisition and research methodology. She is currently a professor in the Department of Linguistics at Georgetown University. Her research focuses on applied linguistics and research methods.

References

- ↑ Johnson, Keith; Johnson, Helen, eds. (1999). "Interaction Hypothesis". Encyclopedic Dictionary of Applied Linguistics: A Handbook for Language Teaching. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-631-22767-0.

- 1 2 Gass, S. M., and Mackey, A. (2007). Input, interaction, and output in second language acquisition. In B. VanPatten and J. Williams (Eds.), Theories in second language acquisition: An introduction (pp. 175-199). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- 1 2 Lightbown, P. M. & Spada, N. (2013). How Languages are Learned (4th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-454126-8

- ↑ Long, Michael (1985). "Input and Second Language Acquisition Theory". In Gass, Susan; Madden, Carolyn (eds.). Input in second language acquisition. Rowley, Mass: Newbury House. pp. 377–393. ISBN 978-0-88377-284-3.

- ↑ Ellis, Rod (1984). Classroom Second Language Development: A Study of Classroom Interaction and Language Acquisition. Oxford, UK: Pergamon. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-08-031516-4.

- 1 2 3 4 Ellis, R. (1991). The Interaction Hypothesis: A Critical Evaluation. Language Acquisition and the Second/Foreign Language, 179. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED367161.pdf#page=191

- 1 2 3 Long, Michael H. (1981). "Input, Interaction, and Second-Language Acquisition". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 379 (1): 259–278. Bibcode:1981NYASA.379..259L. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1981.tb42014.x. S2CID 85137184.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ellis, Rod (1997). Second Language Acquisition. Oxford Introductions to Language Study. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 47–48. ISBN 978-0-19-437212-1.

- 1 2 3 Richards, Jack; Schmidt, Richard, eds. (2002). "Interaction Hypothesis". Longman dictionary of language teaching and applied linguistics. London New York: Longman. p. 264. ISBN 978-0-582-43825-5.

- ↑ Long, M. H. (1983). "Native speaker/Non-native speaker conversation and the negotiation of comprehensible input1". Applied Linguistics. 4 (2): 126–141. doi:10.1093/applin/4.2.126.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Long, M. (1996). The role of the linguistic environment in second language acquisition. In W. Ritchie and T. Bhatia (eds), Handbook of Second Language Acquisition. San Diego: Academic Press, 413 – 68.

- 1 2 Gass, Susan; Selinker, Larry (2008). Second Language Acquisition: An Introductory Course . New York, NY: Routledge. p. 350. ISBN 978-0-8058-5497-8.

- ↑ For an overview, see Gass, Susan; Selinker, Larry (2008). Second Language Acquisition: An Introductory Course . New York, NY: Routledge. pp. 353–355. ISBN 978-0-8058-5497-8.

- ↑ Brown, H Douglas (2000). Principles of Language Learning and Teaching. White Plains, NY: Longman. pp. 287–288. ISBN 978-0-13-017816-9.

- ↑ Larsen-Freeman, Diane; Long, Michael (1991). An Introduction to Second Language Acquisition Research. London, New York: Longman. pp. 143–144. ISBN 978-0-582-55377-4.

- 1 2 3 Krashen, S. (1980). The Input Hypothesis. London: Longman. https://www.uio.no/studier/emner/hf/iln/LING4140/h08/The%20Input%20Hypothesis.pdf

- ↑ Long, M. H. (1989). Task, group, and task-group interactions. University of Hawaii working papers in ESL, 8(2), 1-26. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED366184.pdf

- ↑ Swain, M. (1985) Communicative competence: Some roles of comprehensible input and comprehensible output in its development. In Lightbown, P. M. & Spada, N. (2013), How languages are learned. pp. 114-115. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press

- ↑ Pica, Teresa; Young, Richard; Doughty, Catherine (1987). "The Impact of Interaction on Comprehension". TESOL Quarterly. 21 (4): 737–758. doi:10.2307/3586992. JSTOR 3586992.

- ↑ Pica, T. (1987). "Second-Language Acquisition, Social Interaction, and the Classroom". Applied Linguistics. 8: 3–21. doi:10.1093/applin/8.1.3.

- 1 2 Ellis, R. (2008). The study of second language acquisition. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.