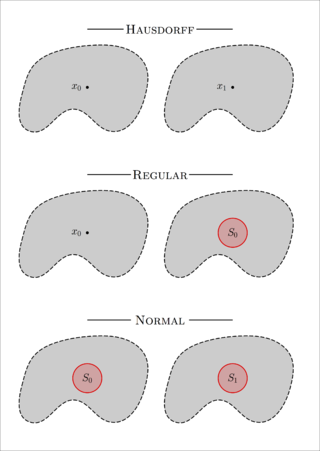

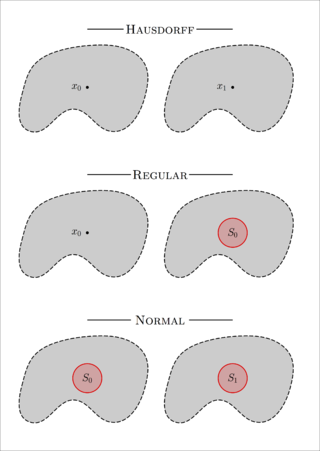

In topology and related branches of mathematics, a Hausdorff space ( HOWSS-dorf, HOWZ-dorf), separated space or T2 space is a topological space where, for any two distinct points, there exist neighbourhoods of each that are disjoint from each other. Of the many separation axioms that can be imposed on a topological space, the "Hausdorff condition" (T2) is the most frequently used and discussed. It implies the uniqueness of limits of sequences, nets, and filters.

In mathematics, a metric space is a set together with a notion of distance between its elements, usually called points. The distance is measured by a function called a metric or distance function. Metric spaces are the most general setting for studying many of the concepts of mathematical analysis and geometry.

In mathematics, a normed vector space or normed space is a vector space over the real or complex numbers on which a norm is defined. A norm is a generalization of the intuitive notion of "length" in the physical world. If is a vector space over , where is a field equal to or to , then a norm on is a map , typically denoted by , satisfying the following four axioms:

- Non-negativity: for every ,.

- Positive definiteness: for every , if and only if is the zero vector.

- Absolute homogeneity: for every and ,

- Triangle inequality: for every and ,

In topology and related branches of mathematics, Tychonoff spaces and completely regular spaces are kinds of topological spaces. These conditions are examples of separation axioms. A Tychonoff space is any completely regular space that is also a Hausdorff space; there exist completely regular spaces that are not Tychonoff.

This is a glossary of some terms used in the branch of mathematics known as topology. Although there is no absolute distinction between different areas of topology, the focus here is on general topology. The following definitions are also fundamental to algebraic topology, differential topology and geometric topology.

In mathematics, a topological vector space is one of the basic structures investigated in functional analysis. A topological vector space is a vector space that is also a topological space with the property that the vector space operations are also continuous functions. Such a topology is called a vector topology and every topological vector space has a uniform topological structure, allowing a notion of uniform convergence and completeness. Some authors also require that the space is a Hausdorff space. One of the most widely studied categories of TVSs are locally convex topological vector spaces. This article focuses on TVSs that are not necessarily locally convex. Banach spaces, Hilbert spaces and Sobolev spaces are other well-known examples of TVSs.

In topology and related fields of mathematics, a topological space X is called a regular space if every closed subset C of X and a point p not contained in C admit non-overlapping open neighborhoods. Thus p and C can be separated by neighborhoods. This condition is known as Axiom T3. The term "T3 space" usually means "a regular Hausdorff space". These conditions are examples of separation axioms.

In mathematics, a pseudometric space is a generalization of a metric space in which the distance between two distinct points can be zero. Pseudometric spaces were introduced by Đuro Kurepa in 1934. In the same way as every normed space is a metric space, every seminormed space is a pseudometric space. Because of this analogy, the term semimetric space is sometimes used as a synonym, especially in functional analysis.

In topology and related branches of mathematics, a T1 space is a topological space in which, for every pair of distinct points, each has a neighborhood not containing the other point. An R0 space is one in which this holds for every pair of topologically distinguishable points. The properties T1 and R0 are examples of separation axioms.

In mathematics, general topology is the branch of topology that deals with the basic set-theoretic definitions and constructions used in topology. It is the foundation of most other branches of topology, including differential topology, geometric topology, and algebraic topology.

In mathematics, particularly in functional analysis, a seminorm is a vector space norm that need not be positive definite. Seminorms are intimately connected with convex sets: every seminorm is the Minkowski functional of some absorbing disk and, conversely, the Minkowski functional of any such set is a seminorm.

In functional analysis and related areas of mathematics, locally convex topological vector spaces (LCTVS) or locally convex spaces are examples of topological vector spaces (TVS) that generalize normed spaces. They can be defined as topological vector spaces whose topology is generated by translations of balanced, absorbent, convex sets. Alternatively they can be defined as a vector space with a family of seminorms, and a topology can be defined in terms of that family. Although in general such spaces are not necessarily normable, the existence of a convex local base for the zero vector is strong enough for the Hahn–Banach theorem to hold, yielding a sufficiently rich theory of continuous linear functionals.

In mathematics, a norm is a function from a real or complex vector space to the non-negative real numbers that behaves in certain ways like the distance from the origin: it commutes with scaling, obeys a form of the triangle inequality, and is zero only at the origin. In particular, the Euclidean distance in a Euclidean space is defined by a norm on the associated Euclidean vector space, called the Euclidean norm, the 2-norm, or, sometimes, the magnitude of the vector. This norm can be defined as the square root of the inner product of a vector with itself.

In topology and related areas of mathematics, a topological property or topological invariant is a property of a topological space that is invariant under homeomorphisms. Alternatively, a topological property is a proper class of topological spaces which is closed under homeomorphisms. That is, a property of spaces is a topological property if whenever a space X possesses that property every space homeomorphic to X possesses that property. Informally, a topological property is a property of the space that can be expressed using open sets.

In functional analysis and related areas of mathematics, a set in a topological vector space is called bounded or von Neumann bounded, if every neighborhood of the zero vector can be inflated to include the set. A set that is not bounded is called unbounded.

In topology, two points of a topological space X are topologically indistinguishable if they have exactly the same neighborhoods. That is, if x and y are points in X, and Nx is the set of all neighborhoods that contain x, and Ny is the set of all neighborhoods that contain y, then x and y are "topologically indistinguishable" if and only if Nx = Ny. (See Hausdorff's axiomatic neighborhood systems.)

In mathematics, a finite topological space is a topological space for which the underlying point set is finite. That is, it is a topological space which has only finitely many elements.

In topology and related fields of mathematics, there are several restrictions that one often makes on the kinds of topological spaces that one wishes to consider. Some of these restrictions are given by the separation axioms. These are sometimes called Tychonoff separation axioms, after Andrey Tychonoff.

In mathematics, Kolmogorov's normability criterion is a theorem that provides a necessary and sufficient condition for a topological vector space to be normable; that is, for the existence of a norm on the space that generates the given topology. The normability criterion can be seen as a result in same vein as the Nagata–Smirnov metrization theorem and Bing metrization theorem, which gives a necessary and sufficient condition for a topological space to be metrizable. The result was proved by the Russian mathematician Andrey Nikolayevich Kolmogorov in 1934.

In functional analysis and related areas of mathematics, a metrizable topological vector space (TVS) is a TVS whose topology is induced by a metric. An LM-space is an inductive limit of a sequence of locally convex metrizable TVS.