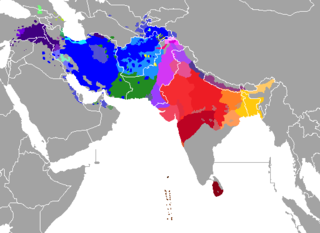

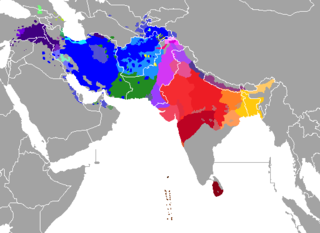

The Indo-Iranian languages constitute the largest and southeasternmost extant branch of the Indo-European language family. They include over 300 languages, spoken by around 1.5 billion speakers, predominantly in South Asia, West Asia and parts of Central Asia.

The Italic languages form a branch of the Indo-European language family, whose earliest known members were spoken on the Italian Peninsula in the first millennium BC. The most important of the ancient languages was Latin, the official language of ancient Rome, which conquered the other Italic peoples before the common era. The other Italic languages became extinct in the first centuries AD as their speakers were assimilated into the Roman Empire and shifted to some form of Latin. Between the third and eighth centuries AD, Vulgar Latin diversified into the Romance languages, which are the only Italic languages natively spoken today, while Literary Latin also survived.

The Tocharianlanguages, also known as Arśi-Kuči, Agnean-Kuchean or Kuchean-Agnean, are an extinct branch of the Indo-European language family spoken by inhabitants of the Tarim Basin, the Tocharians. The languages are known from manuscripts dating from the 5th to the 8th century AD, which were found in oasis cities on the northern edge of the Tarim Basin and the Lop Desert. The discovery of these languages in the early 20th century contradicted the formerly prevalent idea of an east–west division of the Indo-European language family as centum and satem languages, and prompted reinvigorated study of the Indo-European family. Scholars studying these manuscripts in the early 20th century identified their authors with the Tokharoi, a name used in ancient sources for people of Bactria (Tokharistan). Although this identification is now believed to be mistaken, "Tocharian" remains the usual term for these languages.

The Anatolian languages are an extinct branch of Indo-European languages that were spoken in Anatolia, part of present-day Turkey. The best known Anatolian language is Hittite, which is considered the earliest-attested Indo-European language.

The Tocharians, or Tokharians, were speakers of Tocharian languages, Indo-European languages known from around 7,600 documents from around 400 to 1200 AD, found on the northern edge of the Tarim Basin . The name "Tocharian" was given to these languages in the early 20th century by scholars who identified their speakers with a people known in ancient Greek sources as the Tókharoi, who inhabited Bactria from the 2nd century BC. This identification is generally considered erroneous, but the name "Tocharian" remains the most common term for the languages and their speakers. Their actual ethnic name is unknown, although they may have referred to themselves as Agni, Kuči, and Krorän, or Agniya, Kuchiya as known from Sanskrit texts.

Palaic is an extinct Indo-European language, attested in cuneiform tablets in Bronze Age Hattusa, the capital of the Hittites. Palaic, which was apparently spoken mainly in northern Anatolia, is generally considered to be one of four primary sub-divisions of the Anatolian languages, alongside Hittite, Luwic and Lydian.

Kucha or Kuche was an ancient Buddhist kingdom located on the branch of the Silk Road that ran along the northern edge of what is now the Taklamakan Desert in the Tarim Basin and south of the Muzat River.

In Indo-European linguistics, the term Indo-Hittite refers to Edgar Howard Sturtevant's 1926 hypothesis that the Anatolian languages may have split off a Pre-Proto-Indo-European language considerably earlier than the separation of the remaining Indo-European languages. The term may be somewhat confusing, as the prefix Indo- does not refer to the Indo-Aryan branch in particular, but is iconic for Indo-European, and the -Hittite part refers to the Anatolian language family as a whole.

Douglas Quentin Adams is an American linguist, professor of English at the University of Idaho and an Indo-European comparativist. He studied at the University of Chicago, earning PhD in 1972. Adams is an expert on Tocharian and a contributor on this subject to the Encyclopædia Britannica.

The numerals and derived numbers of the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) have been reconstructed by modern linguists based on similarities found across all Indo-European languages. The following article lists and discusses their hypothesized forms.

Hieroglyphic Luwian (luwili) is a variant of the Luwian language, recorded in official and royal seals and a small number of monumental inscriptions. It is written in a hieroglyphic script known as Anatolian hieroglyphs.

Some loanwords in the variant of the Hurrian language spoken in the Mitanni kingdom, during the 2nd millennium BCE, are identifiable as originating in an Indo-Aryan language; these are considered to constitute an Indo-Aryan superstrate in Mitanni. The words in question are theonyms, proper names and technical terminology related to horses (hippological).

The Tocharian script, also known as Central Asian slanting Gupta script or North Turkestan Brāhmī, is an abugida which uses a system of diacritical marks to associate vowels with consonant symbols. Part of the Brahmic scripts, it is a version of the Indian Brahmi script. It is used to write the Central Asian Indo-European Tocharian languages, mostly from the 8th century that were written on palm leaves, wooden tablets and Chinese paper, preserved by the extremely dry climate of the Tarim Basin. Samples of the language have been discovered at sites in Kucha and Karasahr, including many mural inscriptions. Mistakenly identifying the speakers of this language with the Tokharoi people of Tokharistan, early authors called these languages "Tocharian". This naming has remained, although the names Agnean and Kuchean have been proposed as a replacement.

Jay Harold Jasanoff is an American linguist and Indo-Europeanist, best known for his h2e-conjugation theory of the Proto-Indo-European verbal system. He teaches Indo-European linguistics and historical linguistics at Harvard University.

The following is a table of many of the most fundamental Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) words and roots, with their cognates in all of the major families of descendants.

Turkic peoples began settling in the Tarim Basin in the 7th century. The first settlers were likely Tang-allied Türk (Tujue) tribes. The area was later settled by the Uyghur people, who founded the Qocho Kingdom there in the 9th century. The historical area of what is modern-day Xinjiang consisted of the distinct areas of the Tarim Basin and Dzungaria. The area was first populated by Indo-European Tocharian and Saka peoples, who practiced Buddhism. The Tocharian and Saka peoples came under Chinese rule in the Han dynasty as the Protectorate of the Western Regions due to wars between the Han dynasty and the Xiongnu and again in the Tang dynasty as the Protectorate General to Pacify the West due to wars between the Tang dynasty and the First, Western, and Eastern Turkic Khaganates. The Tang dynasty withdrew its control of the region in the Protectorate General to Pacify the West and the Four Garrisons of Anxi after the An Lushan Rebellion, after which the Turkic peoples and the other native inhabitants living in the area gradually converted to Islam.

Maitreyasamitināṭaka is a Buddhist drama in the language known as Tocharian A. It dates to the eighth century and survives only in fragments. Maitrisimit nom bitig is an Old Uyghur translation of the Tocharian text. It is a much more complete text and dates to the tenth century. The drama revolves around the Buddha Maitreya, the future saviour of the world. This story was popular among Buddhists and parallel versions can be found in Chinese, Tibetan, Khotanese, Sogdian, Pali and Sanskrit. According to Friedrich W. K. Müller and Emil Sieg, the apparent meaning of the title is "Encounter with Maitreya".

Suvarṇapuṣpa was a King of the Tarim Basin city-state of Kucha from 600 to 625. He was known in Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit (BHS) as Kucīśvara Suvarṇapuṣpa "Suvarṇapuṣpa, lord of Kucha". He was known in Chinese as Bái Sūfábójué as he sent an embassy to the court of the Tang dynasty in 618 CE acknowledging vassalship.

Melanie Malzahn is a German professor of Indo-European studies at the University of Vienna specializing in the history of the Tocharian languages.