Greek is an independent branch of the Indo-European family of languages, native to Greece, Cyprus, Italy, southern Albania, and other regions of the Balkans, the Black Sea coast, Asia Minor, and the Eastern Mediterranean. It has the longest documented history of any Indo-European language, spanning at least 3,400 years of written records. Its writing system is the Greek alphabet, which has been used for approximately 2,800 years; previously, Greek was recorded in writing systems such as Linear B and the Cypriot syllabary. The alphabet arose from the Phoenician script and was in turn the basis of the Latin, Cyrillic, Coptic, Gothic, and many other writing systems.

Demographic features of the population of Turkey include population density, ethnicity, education level, health of the populace, economic status, religious affiliations and other aspects of the population.

The Treaty of Lausanne is a peace treaty negotiated during the Lausanne Conference of 1922–23 and signed in the Palais de Rumine in Lausanne, Switzerland, on 24 July 1923. The treaty officially resolved the conflict that had initially arisen between the Ottoman Empire and the Allied French Republic, British Empire, Kingdom of Italy, Empire of Japan, Kingdom of Greece, Kingdom of Serbia, and the Kingdom of Romania since the outset of World War I. The original text of the treaty is in English and French. It emerged as a second attempt at peace after the failed and unratified Treaty of Sèvres, which had sought to partition Ottoman territories. The earlier treaty, signed in 1920, was later rejected by the Turkish National Movement which actively opposed its terms. As a result of the Greco-Turkish War, İzmir was reclaimed, and the Armistice of Mudanya was signed in October 1922. This armistice provided for the exchange of Greek-Turkish populations and allowed unrestricted civilian, non-military passage through the Turkish Straits.

The Treaty of Sèvres was a 1920 treaty signed between the Allies of World War I and the Ottoman Empire. The treaty ceded large parts of Ottoman territory to France, the United Kingdom, Greece and Italy, as well as creating large occupation zones within the Ottoman Empire. It was one of a series of treaties that the Central Powers signed with the Allied Powers after their defeat in World War I. Hostilities had already ended with the Armistice of Mudros.

Yevanic, also known as Judaeo-Greek, Romaniyot, Romaniote, and Yevanitika, is a Greek dialect formerly used by the Romaniotes and by the Constantinopolitan Karaites. The Romaniotes are a group of Greek Jews whose presence in the Levant is documented since the Byzantine period. Its linguistic lineage stems from the Jewish Koine spoken primarily by Hellenistic Jews throughout the region, and includes Hebrew and Aramaic elements. It was mutually intelligible with the Greek dialects of the Christian population. The Romaniotes used the Hebrew alphabet to write Greek and Yevanic texts. Judaeo-Greek has had in its history different spoken variants depending on different eras, geographical and sociocultural backgrounds. The oldest Modern Greek text was found in the Cairo Geniza and is actually a Jewish translation of the Book of Ecclesiastes (Kohelet).

The history of the Jews in Turkey covers the 2400 years that Jews have lived in what is now Turkey.

Assyrians in Turkey or Turkish Assyrians are an indigenous Semitic-speaking ethnic group and minority of Turkey who are Eastern Aramaic–speaking Christians, with most being members of the Syriac Orthodox Church, Chaldean Catholic Church, Assyrian Pentecostal Church, Assyrian Evangelical Church, or Ancient Church of the East.

Education in Turkey is governed by a national system which was established in accordance with the Atatürk's Reforms. It is a state-supervised system designed to produce a skillful professional class for the social and economic institutes of the nation.

Turkification, Turkization, or Turkicization describes a shift whereby populations or places received or adopted Turkic attributes such as culture, language, history, or ethnicity. However, often this term is more narrowly applied to mean specifically Turkish rather than merely Turkic, meaning that it refers more frequently to the Ottoman Empire's policies or the Turkish nationalist policies of the Republic of Turkey toward ethnic minorities in Turkey. As the Turkic states developed and grew, there were many instances of this cultural shift.

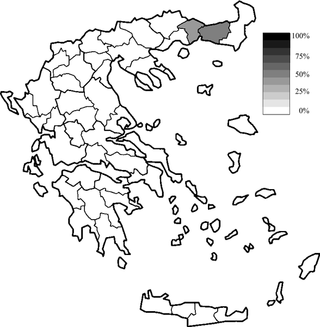

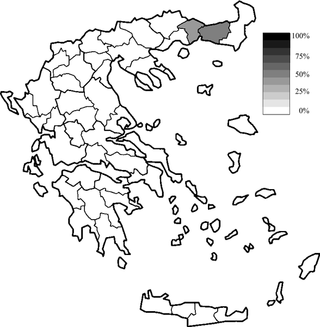

Minorities in Greece are small in size compared to Balkan regional standards, and the country is largely ethnically homogeneous. This is mainly due to the population exchanges between Greece and neighboring Turkey and Bulgaria, which removed most Muslims and those Christian Slavs who did not identify as Greeks from Greek territory. The treaty also provided for the resettlement of ethnic Greeks from those countries, later to be followed by refugees. There is no official information for the size of the ethnic, linguistic and religious minorities because asking the population questions pertaining to the topic have been abolished since 1951.

Armenians in Turkey, one of the indigenous peoples of Turkey, have an estimated population of 50,000 to 70,000, down from a population of over 2 million Armenians between the years 1914 and 1921. Today, the overwhelming majority of Turkish Armenians are concentrated in Istanbul. They support their own newspapers, churches and schools, and the majority belong to the Armenian Apostolic faith and a minority of Armenians in Turkey belong to the Armenian Catholic Church or to the Armenian Evangelical Church. They are not considered part of the Armenian Diaspora, since they have been living in their historical homeland for more than four thousand years.

The Greeks in Turkey constitute a small population of Greek and Greek-speaking Eastern Orthodox Christians who mostly live in Istanbul, as well as on the two islands of the western entrance to the Dardanelles: Imbros and Tenedos. Greeks are one of the four ethnic minorities officially recognized in Turkey by the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, together with Jews, Armenians, and Bulgarians.

Turks of Western Thrace are ethnic Turks who live in Western Thrace, in the province of East Macedonia and Thrace in Northern Greece.

The Muslim minority of Greece is the only explicitly recognized minority in Greece. It numbered 97,605 according to the 1991 census, and unofficial estimates ranged up to 140,000 people or 1.24% of the total population, according to the United States Department of State.

The partition of the Ottoman Empire was a geopolitical event that occurred after World War I and the occupation of Constantinople by British, French, and Italian troops in November 1918. The partitioning was planned in several agreements made by the Allied Powers early in the course of World War I, notably the Sykes–Picot Agreement, after the Ottoman Empire had joined Germany to form the Ottoman–German Alliance. The huge conglomeration of territories and peoples that formerly comprised the Ottoman Empire was divided into several new states. The Ottoman Empire had been the leading Islamic state in geopolitical, cultural and ideological terms. The partitioning of the Ottoman Empire after the war led to the domination of the Middle East by Western powers such as Britain and France, and saw the creation of the modern Arab world and the Republic of Turkey. Resistance to the influence of these powers came from the Turkish National Movement but did not become widespread in the other post-Ottoman states until the period of rapid decolonization after World War II.

Kurdish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which asserts that Kurds are a nation and espouses the creation of an independent Kurdistan from Iran, Iraq, Syria, and Turkey.

Minorities in Turkey form a substantial part of the country's population, representing an estimated 25 to 28 percent of the population. Historically, in the Ottoman Empire, Islam was the official and dominant religion, with Muslims having more rights than non-Muslims, whose rights were restricted. Non-Muslim (dhimmi) ethno-religious groups were legally identified by different millet ("nations").

The language of the court and government of the Ottoman Empire was Ottoman Turkish, but many other languages were in contemporary use in parts of the empire. The Ottomans had three influential languages, known as "Alsina-i Thalātha", that were common to Ottoman readers: Ottoman Turkish, Arabic and Persian. Turkish was spoken by the majority of the people in Anatolia and by the majority of Muslims of the Balkans except in Albania, Bosnia, and various Aegean Sea islands; Persian was initially a literary and high-court language used by the educated in the Ottoman Empire before being displaced by Ottoman Turkish; and Arabic, which was the legal and religious language of the empire, was also spoken regionally, mainly in Arabia, North Africa, Mesopotamia and the Levant.

In Turkey, xenophobia and discrimination are present in its society and throughout its history, including ethnic discrimination, religious discrimination and institutional racism against non-Muslim and non-Sunni minorities. This appears mainly in the form of negative attitudes and actions by some people towards people who are not considered ethnically Turkish, notably Kurds, Armenians, Arabs, Assyrians, Greeks, Jews, and peripatetic groups like Romani people, Domari, Abdals and Lom.

The Citizen, speak Turkish! campaign was a Turkish government-funded initiative created by law students which aimed to put pressure on non-Turkish speakers to speak Turkish in public in the 1930s and onwards. In some municipalities, fines were given to those speaking in any language other than Turkish. The campaign has been considered by some authors as a significant contribution to Turkey's sociopolitical process of Turkification.