The Mustelidae are a diverse family of carnivorous mammals, including weasels, stoats, badgers, otters, martens, grisons, and wolverines. Otherwise known as mustelids, they form the largest family in the suborder Caniformia of the order Carnivora with about 66 to 70 species in nine subfamilies.

Otters are carnivorous mammals in the subfamily Lutrinae. The 13 extant otter species are all semiaquatic, aquatic, or marine. Lutrinae is a branch of the Mustelidae family, which includes weasels, badgers, mink, and wolverines, among other animals.

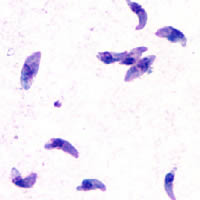

Toxoplasma gondii is a parasitic protozoan that causes toxoplasmosis. Found worldwide, T. gondii is capable of infecting virtually all warm-blooded animals, but felids are the only known definitive hosts in which the parasite may undergo sexual reproduction.

The sea otter is a marine mammal native to the coasts of the northern and eastern North Pacific Ocean. Adult sea otters typically weigh between 14 and 45 kg, making them the heaviest members of the weasel family, but among the smallest marine mammals. Unlike most marine mammals, the sea otter's primary form of insulation is an exceptionally thick coat of fur, the densest in the animal kingdom. Although it can walk on land, the sea otter is capable of living exclusively in the ocean.

The Fuegian steamer duck or the Magellanic flightless steamer duck, is a flightless duck native to South America. It belongs to the steamer duck genus Tachyeres. It inhabits the rocky coasts and coastal islands from southern Chile and Chiloé to Tierra del Fuego, switching to the adjacent sheltered bays and lakes further inland when breeding.

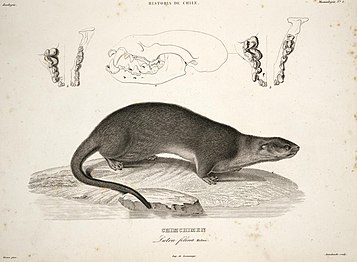

Lontra is a genus of otters from the Americas.

The North American river otter, also known as the northern river otter and river otter, is a semiaquatic mammal that lives only on the North American continent, along its waterways and coasts. An adult North American river otter can weigh between 5.0 and 14 kg. The river otter is protected and insulated by a thick, water-repellent coat of fur.

Lutra is a genus of otters, one of seven in the subfamily Lutrinae.

The giant otter or giant river otter is a South American carnivorous mammal. It is the longest member of the weasel family, Mustelidae, a globally successful group of predators, reaching up to 1.8 m. Atypical of mustelids, the giant otter is a social species, with family groups typically supporting three to eight members. The groups are centered on a dominant breeding pair and are extremely cohesive and cooperative. Although generally peaceful, the species is territorial, and aggression has been observed between groups. The giant otter is diurnal, being active exclusively during daylight hours. It is the noisiest otter species, and distinct vocalizations have been documented that indicate alarm, aggression, and reassurance.

The Neotropical otter or Neotropical river otter is an otter species found in Mexico, Central America, South America, and the island of Trinidad. It is physically similar to the northern and southern river otter, which occur directly north and south of this species' range. Its head-and-body length can range from 36–66 centimetres (14–26 in), plus a tail of 37–84 centimetres (15–33 in). Body weight ranges from 5–15 kilograms (11–33 lb). Otters are members of the family Mustelidae, the most species-rich family in the order Carnivora.

Aquatic and semiaquatic mammals are a diverse group of mammals that dwell partly or entirely in bodies of water. They include the various marine mammals who dwell in oceans, as well as various freshwater species, such as the European otter. They are not a taxon and are not unified by any distinct biological grouping, but rather their dependence on and integral relation to aquatic ecosystems. The level of dependence on aquatic life varies greatly among species. Among freshwater taxa, the Amazonian manatee and river dolphins are completely aquatic and fully dependent on aquatic ecosystems. Semiaquatic freshwater taxa include the Baikal seal, which feeds underwater but rests, molts, and breeds on land; and the capybara and hippopotamus which are able to venture in and out of water in search of food.

The southern river otter, or South American river otter, is an otter species that lives in the southern regions of Argentina and Chile, including parts of Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego. It is listed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as an endangered species.

Guafo Island is an island located southwest of Chiloé Island and northwest of Chonos Archipelago, Chile. This location and the prevailing westerly winds bring frequent rainstorms to the island. Ocean currents bring an abundance of fish into this area, making it one of the most productive marine areas in the Southern Pacific Ocean. Because of this, numerous marine vertebrates such as fur seals, sea lions and penguins come to the island to feed and reproduce.

The Congo clawless otter, also known as the Cameroon clawless otter, is a species in the family Mustelidae. It was formerly recognised as a subspecies of the African clawless otter.

Megalenhydris barbaricina is an extinct species of giant otter from the Late Pleistocene of Sardinia. It is known from a single partial skeleton, discovered in the Grotta di Ispinigoli near Dorgali, and was described in 1987. It was larger than any living otter, exceeding the size of South American giant otters (Petrolutra), which can reach two meters in length. The species is one of four extinct otter species from Sardinia and Corsica. The others are Algarolutra majori, Lutra castiglionis and Sardolutra ichnusae. It is suggested to have ultimately originated from the much smaller European mainland species "Lutra" simplicidens, which may be more closely related to Lutrogale than to modern Lutra species. The structure of the teeth points to a diet of bottom dwelling fish and crustaceans. A special characteristic of the species is the flattening of the first few caudal vertebrae. This might point to a slightly flattened tail.

The sea otter, Enhydra lutris, is a member of the Mustelidae that is fully aquatic. Sea otters are the smallest of the marine mammals, but they are also the most dexterous. Sea otters are known for their ability to use stones as anvils or hammers to facilitate access to hard-to-reach prey items. Furthermore, out of the thirteen currently known species of otters, at least 10 demonstrate stone handling behaviour, suggesting that otters may have a genetic predisposition to manipulate stones. Tool use behavior is more associated with geographic location than sub-species. Most behavioral research has been conducted on Enhydra lutris nereis, the Californian otter, and some has been conducted on Enhydra lutris kenyoni, the Alaska sea otter. Sea otters frequently use rocks as anvils to crack open prey, and they are also observed to rip open prey with their forepaws. While lying on their backs, otters will rip apart coral algae to find food among the debris. The frequency of tool use varies greatly between geographic regions and individual otters. Regardless of the frequency, the use of tools is present in the behavioral repertoire of sea otters and is performed when most appropriate to the situation.

Enhydriodon is an extinct genus of mustelids known from Africa, Pakistan and India that lived from the late Miocene to the early Pleistocene. It contains 9 confirmed species, 2 debated species, and at least a few other undescribed species from Africa. The genus belongs to the tribe Enhydriodontini in the otter subfamily Lutrinae. Enhydriodon means "otter tooth" in Ancient Greek and is a reference to its dentition rather than to the Enhydra genus, which includes the modern sea otter and its two prehistoric relatives.

Siamogale melilutra is an extinct species of giant otter from the late Miocene from Yunnan province, China.

Lontra weiri is a fossil species in the carnivoran family Mustelidae from the Hagerman Fossil Beds of Idaho. It shared its habitat with Satherium piscinarium, a probable ancestor of the giant otter of South America. It is named in honor of musician Bob Weir, and is the oldest known member of its genus. Prior to its discovery, Lontra was thought to have evolved from Lutra licenti, which dates from the Pleistocene of East Asia.