The California Air Resources Board is an agency of the government of California that aims to reduce air pollution. Established in 1967 when then-governor Ronald Reagan signed the Mulford-Carrell Act, combining the Bureau of Air Sanitation and the Motor Vehicle Pollution Control Board, CARB is a department within the cabinet-level California Environmental Protection Agency.

Vehicle emissions control is the study of reducing the emissions produced by motor vehicles, especially internal combustion engines.

Emission standards are the legal requirements governing air pollutants released into the atmosphere. Emission standards set quantitative limits on the permissible amount of specific air pollutants that may be released from specific sources over specific timeframes. They are generally designed to achieve air quality standards and to protect human life. Different regions and countries have different standards for vehicle emissions.

A zero-emission vehicle, or ZEV, is a vehicle that does not emit exhaust gas or other pollutants from the onboard source of power. The California definition also adds that this includes under any and all possible operational modes and conditions. This is because under cold-start conditions for example, internal combustion engines tend to produce the maximum amount of pollutants. In a number of countries and states, transport is cited as the main source of greenhouse gases (GHG) and other pollutants. The desire to reduce this is thus politically strong.

Exhaust gas or flue gas is emitted as a result of the combustion of fuels such as natural gas, gasoline (petrol), diesel fuel, fuel oil, biodiesel blends, or coal. According to the type of engine, it is discharged into the atmosphere through an exhaust pipe, flue gas stack, or propelling nozzle. It often disperses downwind in a pattern called an exhaust plume.

A green vehicle, clean vehicle, eco-friendly vehicle or environmentally friendly vehicle is a road motor vehicle that produces less harmful impacts to the environment than comparable conventional internal combustion engine vehicles running on gasoline or diesel, or one that uses certain alternative fuels. Presently, in some countries the term is used for any vehicle complying or surpassing the more stringent European emission standards, or California's zero-emissions vehicle standards, or the low-carbon fuel standards enacted in several countries.

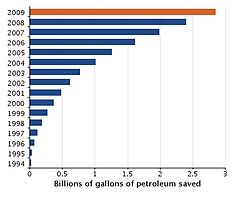

The fuel economy of an automobile relates to the distance traveled by a vehicle and the amount of fuel consumed. Consumption can be expressed in terms of the volume of fuel to travel a distance, or the distance traveled per unit volume of fuel consumed. Since fuel consumption of vehicles is a significant factor in air pollution, and since the importation of motor fuel can be a large part of a nation's foreign trade, many countries impose requirements for fuel economy. Different methods are used to approximate the actual performance of the vehicle. The energy in fuel is required to overcome various losses encountered while propelling the vehicle, and in providing power to vehicle systems such as ignition or air conditioning. Various strategies can be employed to reduce losses at each of the conversions between the chemical energy in the fuel and the kinetic energy of the vehicle. Driver behavior can affect fuel economy; maneuvers such as sudden acceleration and heavy braking waste energy.

The Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007, originally named the Clean Energy Act of 2007, is an Act of Congress concerning the energy policy of the United States. As part of the Democratic Party's 100-Hour Plan during the 110th Congress, it was introduced in the United States House of Representatives by Representative Nick Rahall of West Virginia, along with 198 cosponsors. Even though Rahall was 1 of only 4 Democrats to oppose the final bill, it passed in the House without amendment in January 2007. When the Act was introduced in the Senate in June 2007, it was combined with Senate Bill S. 1419: Renewable Fuels, Consumer Protection, and Energy Efficiency Act of 2007. This amended version passed the Senate on June 21, 2007. After further amendments and negotiation between the House and Senate, a revised bill passed both houses on December 18, 2007 and President Bush, a Republican, signed it into law on December 19, 2007, in response to his "Twenty in Ten" challenge to reduce gasoline consumption by 20% in 10 years.

A mobile emission reduction credit (MERC) is an emission reduction credit generated within the transportation sector. The term “mobile sources” refers to motor vehicles, engines, and equipment that move, or can be moved, from place to place. Mobile sources include vehicles that operate on roads and highways ("on-road" or "highway" vehicles), as well as nonroad vehicles, engines, and equipment. Examples of mobile sources are passenger cars, light trucks, large trucks, buses, motorcycles, earth-moving equipment, nonroad recreational vehicles (such as dirt bikes and snowmobiles), farm and construction equipment, cranes, lawn and garden power tools, marine engines, ships, railroad locomotives, and airplanes. In California, mobile sources account for about 60 percent of all ozone forming emissions and for over 90 percent of all carbon monoxide (CO) emissions from all sources.

The United States produced 5.2 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in 2020, the second largest in the world after greenhouse gas emissions by China and among the countries with the highest greenhouse gas emissions per person. In 2019 China is estimated to have emitted 27% of world GHG, followed by the United States with 11%, then India with 6.6%. In total the United States has emitted a quarter of world GHG, more than any other country. Annual emissions are over 15 tons per person and, amongst the top eight emitters, is the highest country by greenhouse gas emissions per person. However, the IEA estimates that the richest decile in the US emits over 55 tonnes of CO2 per capita each year. Because coal-fired power stations are gradually shutting down, in the 2010s emissions from electricity generation fell to second place behind transportation which is now the largest single source. In 2020, 27% of the GHG emissions of the United States were from transportation, 25% from electricity, 24% from industry, 13% from commercial and residential buildings and 11% from agriculture. In 2021, the electric power sector was the second largest source of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, accounting for 25% of the U.S. total. These greenhouse gas emissions are contributing to climate change in the United States, as well as worldwide.

The Global Warming Pollution Reduction Act of 2007 (S. 309) was a bill proposed to amend the 1963 Clean Air Act, a bill that aimed to reduce emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2). A U.S. Senator, Bernie Sanders (I-VT), introduced the resolution in the 110th United States Congress on January 16, 2007. The bill was referred to the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works but was not enacted into law.

United States vehicle emission standards are set through a combination of legislative mandates enacted by Congress through Clean Air Act (CAA) amendments from 1970 onwards, and executive regulations managed nationally by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and more recently along with the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). These standard cover common motor vehicle air pollution, including carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, and particulate emissions, and newer versions have incorporated fuel economy standards.

Title 40 is a part of the United States Code of Federal Regulations. Title 40 arranges mainly environmental regulations that were promulgated by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), based on the provisions of United States laws. Parts of the regulation may be updated annually on July 1.

The Clean Air Act (CAA) is the United States' primary federal air quality law, intended to reduce and control air pollution nationwide. Initially enacted in 1963 and amended many times since, it is one of the United States' first and most influential modern environmental laws.

A low-carbon fuel standard (LCFS) is an emissions trading rule designed to reduce the average carbon intensity of transportation fuels in a given jurisdiction, as compared to conventional petroleum fuels, such as gasoline and diesel. The most common methods for reducing transportation carbon emissions are supplying electricity to electric vehicles, supplying hydrogen fuel to fuel cell vehicles and blending biofuels, such as ethanol, biodiesel, renewable diesel, and renewable natural gas into fossil fuels. The main purpose of a low-carbon fuel standard is to decrease carbon dioxide emissions associated with vehicles powered by various types of internal combustion engines while also considering the entire life cycle, in order to reduce the carbon footprint of transportation.

Air quality laws govern the emission of air pollutants into the atmosphere. A specialized subset of air quality laws regulate the quality of air inside buildings. Air quality laws are often designed specifically to protect human health by limiting or eliminating airborne pollutant concentrations. Other initiatives are designed to address broader ecological problems, such as limitations on chemicals that affect the ozone layer, and emissions trading programs to address acid rain or climate change. Regulatory efforts include identifying and categorising air pollutants, setting limits on acceptable emissions levels, and dictating necessary or appropriate mitigation technologies.

United States policy in regard to biofuels, such as ethanol fuel and biodiesel, began in the early 1990s as the government began looking more intensely at biofuels as a way to reduce dependence on foreign oil and increase the nation's overall sustainability. Since then, biofuel policies have been refined, focused on getting the most efficient fuels commercially available, creating fuels that can compete with petroleum-based fuels, and ensuring that the agricultural industry can support and sustain the use of biofuels.

The, United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) began regulating greenhouse gases (GHGs) under the Clean Air Act from mobile and stationary sources of air pollution for the first time on January 2, 2011. Standards for mobile sources have been established pursuant to Section 202 of the CAA, and GHGs from stationary sources are currently controlled under the authority of Part C of Title I of the Act. The basis for regulations was upheld in the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia in June 2012.

Margo T. Oge is an American engineer and environmental regulator who served as the director of the Environmental Protection Agency's Office of Radiation and Indoor Air from 1990 to 1994 and director of the Office of Transportation and Air Quality from 1994 to 2012. Beginning in 2009, Oge lead the EPA team that authored the 2010-2016 and the 2017-2025 Light-Duty Vehicle Greenhouse Gas Emissions Standards. By 2025, these rules require automakers to halve the greenhouse gas emissions of cars and light duty trucks while doubling fuel economy. These rules were the US federal government's first regulatory actions to reduce greenhouse gases.

As the most populous state in the United States, California's climate policies influence both global climate change and federal climate policy. In line with the views of climate scientists, the state of California has progressively passed emission-reduction legislation.